‘Time-travelling millennials: Griffith Review 56’, Honest History, 13 June 2017

Emily Gallagher* reviews Griffith Review 56: Millennials Strike Back

There is no such thing as a normative childhood. Generations of children might share in a collection of culturally specific circumstances, watch the same domestic and international affairs unravel in the newspapers or on the television, play with the same toys, and even indulge in the same fads, but they do so largely in isolation from each other. An awareness of one’s own generation, its oddities and its quirks, comes with age.

It is peculiar then that so many of the contributors to the recent Griffith Review 56: Millennials Strike Back see their childhood memories as evidence of their own generational belonging. Australian millennials are carving out a collective identity for themselves through a shared nostalgia for their youth. They remember pressing the buttons of the first Microsoft computer in childish wonder, installing the next Kellogg’s Nutri Grain CD-ROM promotion on their home desktop, seeing John Howard’s bushy eyebrows dance on the evening news, wandering freely on the scorched, scribbly gum-decorated land of their parents’ farm, and watching two passenger planes fly into the World Trade Centre.

It is peculiar then that so many of the contributors to the recent Griffith Review 56: Millennials Strike Back see their childhood memories as evidence of their own generational belonging. Australian millennials are carving out a collective identity for themselves through a shared nostalgia for their youth. They remember pressing the buttons of the first Microsoft computer in childish wonder, installing the next Kellogg’s Nutri Grain CD-ROM promotion on their home desktop, seeing John Howard’s bushy eyebrows dance on the evening news, wandering freely on the scorched, scribbly gum-decorated land of their parents’ farm, and watching two passenger planes fly into the World Trade Centre.

Remembering childhood, reliving and recreating it in the present, has allowed many of the contributors to this edition to establish a sense of generational belonging. Like their parents before them, they are casting a backward glance at the idealised decade that predates the upheaval and disillusionment of their contemporary lives. In a collection that is not just about millennials but authored by them, Millennials Strike Back echoes the 11-year old The Next Big Thing (2006), offering an honest, talented and provocative exploration of the memories, anxieties and dreams, both imagined and perceived, of a group of successful young academics, journalists, writers, artists, editors and activists.

Like big, red buttons, there is something irresistible about headlines that read: ‘Your generational identity is a lie’, ‘Generation Y should be plotting a revolution’ or ‘Have millennials given up on democracy?’. Since October 2016, the month when avocados became the symbol of an entire generation, nearly every major Australian newspaper has been guilty of using generational references as leading news stories for the thousands of views and ‘likes’ they elicit.

Equally, the Australian public seems to have an insatiable appetite for anything vaguely ‘generational’. Australian Millennials, a Facebook page which is sustained by sentimental posts and comments on 1990s children’s television programs and discontinued lollies, currently has an impressive following of more than 508 000 likes, almost three times the size of the Facebook following for the ABC’s QandA program. As the theme of this edition of the Griffith Review suggests, the millennial has come to represent far more than an arbitrary category of identity.

That said, although ‘the generation’ might be a fashionable form of identity politics for older and younger people alike, it is also a messy affair. As the co-editor Jerath Head reminds readers at the beginning, ‘[t]he idea of a given generation has little to do with the individuals who comprise it, but much to do with the broader forces playing out at the time’. Generations, Head hints, are ‘created’ to serve the interests of various stakeholders, not least parents, economists, business owners and politicians. The sheer breadth and variety of the contributions that follow Head’s essay reinforces the frequently ill-defined nature of generational identities and the extent to which such categories can be interpreted, adopted, rejected and manipulated by the very generation they are ascribed to.

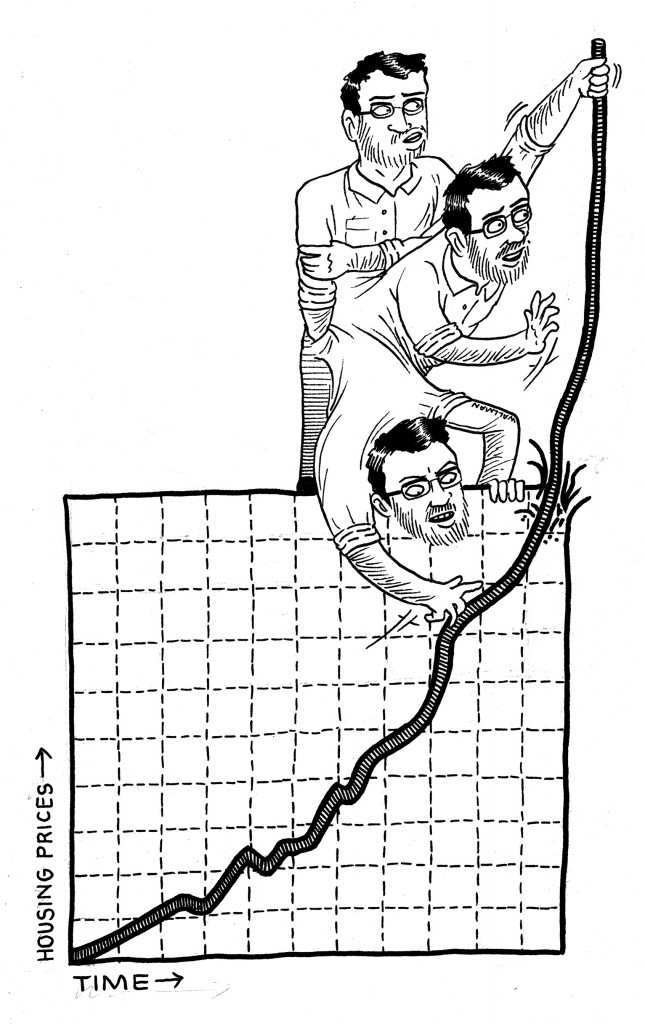

One of the most pronounced tensions that underpins the 35 essays, memoirs, poems, reports, short stories and picture galleries of Millennials Strike Back is the one that exists between the contributors’ sentimental nostalgia for childhood, an urgent preoccupation with the failings of the present, and the seemingly limitless possibilities of the future. ‘The present cannot hold’, concludes Godfrey Moase, Assistant General Branch Secretary at the National Union of Workers. ‘Either we attempt to retreat backwards in time and space from the black hole or we leap through the event horizon and into the unknown future … It is the contest between these two potentials that divides Australia.’

It is also a contest that defines the millennial. In an essay that draws on the experience of pregnancy and childbirth to critique the current direction of neoliberal understandings of labour and work, Research Director at United Voice, Frances Flanagan, both clings to the protections of modern medicine and yearns for an older tradition of humanist medical care. She reminisces about a time when welfare was conceived separately from capitalist profit-making ventures, dwells on the patterns of work and labour that have come to define the contemporary social system, and advocates for a future where welfare does not serve the interests of the state, but where that state serves the interests of its citizens.

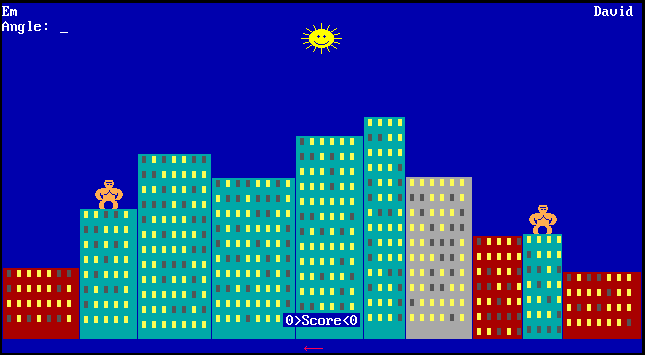

A similar tension between the past, present and future can be seen in Ashley Kalagian Blunt’s memoir, titled ‘Today is already yesterday’. Blunt’s memories of Gorilla.bas, a pixelated video game that was first released on Microsoft in 1991, hurls her into an exploration of the way technology entered her childhood and has since pervaded her adult life. Along the way, she finds herself ‘nostalgic for things that aren’t even gone yet, because I know they will be’. For Blunt, the rapid change and suffocating constancy that has accompanied the digital revolution has stolen the sense of self-control that once characterised her childhood. Yassmin Abdel-Magied, Sudanese-Australian engineer, writer and activist, writes about a similar feeling of vulnerability at the hands of modern digital activism, where individuals are exposed to vicious personal attacks and pointed abuse, a conclusion only amplified by the public response to Abdel-Magied’s Anzac Day Facebook post earlier this year.

Just like Gorilla.bas, Jack Bancroft, CEO and founder of the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience (AIME), remembers the glory years of the internet. A time before YouTube and Instagram developed algorithms to deliver its users information about stuff that they already ‘liked’. Looking back even further, Sam Vincent reminisces about a time before the internet, when his days were spent building hideouts and skinny dipping on his parents’ property. He dreams of inheriting his father’s life of a farmer, a position that would allow him to restore the broken food chains between consumers and producers. Elsewhere, Daniel Jenkins, a writer and teacher from Armidale, New South Wales, offers a shrewd exploration of the politics of race, gender and privilege through a reflection of his own upbringing on Palm Island, Queensland, and rural New South Wales.

Not all the contributors in Millennials Strike Back look back to their childhood in their search for generational belonging. Omar Sakr discovers that he cannot find peace in his childhood when he ‘returns/to the house I grew up in and the house tells/there is no succour to be found in the past’. In her memoir, Kavita Bedford adopts the voice of the child to paint a vivid picture of a child’s capacity for brutality and the gaping intergenerational divisions that separate one generation from the next. And Sophie Allan reflects on her parents’ violent divorce and the complex gendered and social schisms that later infiltrated her family and romantic life.

Following Godfrey Moase’s and Sam Wallman’s graphic essay, the last section of the collection gives attention to many of the bigger concerns that currently occupy the minds of millennials: globalisation, housing affordability, health inequality, sexism and racism in the workplace, sexual violence, Indigenous disadvantage, climate change, sustainability, rising isolationism, and mental illness.

Fiona Wright’s essay on her own long battle with an eating disorder confronts readers with one of Australia’s most troubling struggles: to overcome the stigma of mental illness. At least one in five Australians are living with a mental illness, and as Courtney Landers notes in her essay, ‘[c]ause-of-death statistics released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2015 revealed that suicide is the leading cause of death for people aged fifteen to forty-four’. Beyond the $4.6 billion spent annually on mental-health-related absenteeism in Australia, people are dying – thousands of people are dying.

It is disturbing that in 2017 to admit and speak openly about mental illness is still an act of immense personal vulnerability, which flirts with cultural awkwardness and risks attracting discriminating treatment from others. While today’s young people have frequently been the architects behind the fight against the stigma of mental illness, this fight – just like nearly every other concern raised by the contributors to this Griffith Review – should by no means be a millennial one.

Sam Wallman illustration for GR 56, ‘The housing black hole’ (to go with words by Godfrey Moase here)

Sam Wallman illustration for GR 56, ‘The housing black hole’ (to go with words by Godfrey Moase here)

Like the labelling of a generation, the making of one is a life-long project. The knitting together of an entire generation is as much a coming-of-age story as it is a mere coincidence of one’s birth or a shared childhood. As the contributors to Millennials Strike Back demonstrate, this is a generation that is still very much ‘in the making’. They are riding the currents of the time, anxious about today’s global climate and hopeful about their own shared future in it. John Lennon described the situation best when he denied that the Beatles had written the soundtrack of a generation and led the Baby Boomers through the sixties:

We were all on this ship in the sixties, our generation, a ship going to discover the New World. And the Beatles were in the crow’s nest of that ship … We were going through the changes, and all we were saying was, “It’s raining up here!” or “There’s land!” or “There’s sun!” or “We can see a seagull!” We were just reporting what was happening to us.

Not unlike the Beatles, the contributors to this book are in the crow’s nest of a very big ship, unsure exactly where they are going but nobly seeking to report just what is happening to them to the rest of the world.

* Emily Gallagher is a PhD Candidate at the ANU School of History, the editor of the ANU Historical Journal II and a proud millennial.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.