Then and now: two sad affairs, Honest History, 15 April 2015

Alison Broinowski reviews the Four Corners episode, ‘Anzac to Afghanistan‘

Fran Kelly is off to join the re-invasion at Gallipoli next week. So the count-down begins and pent-up excitement at the ABC could hardly be greater. Imagine if the ‘official broadcaster’ chosen for the centenary had been one of the commercials, and if they had used it for long, tasteless ad-breaks for all the Aussie icons like Rosella, Vegemite, Speedo, Holden, and Anzac ‘cookies’ − all now gone, or under foreign control. But the ABC is doing its best to make up for the absence of commercial nostalgia with long, tasteless ad-breaks for its own coverage of the event. They focus on young Australians for whom, apparently, going to Gallipoli is cool.

Sick and wounded troops waiting to be evacuated from Anzac Cove, August 1915 (Australian War Memorial C00425)

Sick and wounded troops waiting to be evacuated from Anzac Cove, August 1915 (Australian War Memorial C00425)

In the interests of honest historians I made myself watch Four Corners on 13 April, fearing the worst. Chris Masters emerged to re-run selections from his past interviews with old Diggers, all of whom are now dead, intercut with photos of the landing, the trenches, the clifftop, and the retreat. The Anzacs were keen, patriotic and not nervous, according to one man interviewed, even when they went over the top into the gunfire. One in five was born in the United Kingdom. But another admitted to seeing men injure themselves in order to be withdrawn.

They never advanced further than on the first day, one says, and then they spent the next eight months with ‘millions of flies’, body lice, and smells, with only comradeship and the occasional parcel from home to sustain them. By the end, they had developed the skill and cunning to evacuate without even more losses. If there was a common thread, it was the Diggers’ confusion about what they were there for and their sadness about the 8700 dead comrades they left behind. ‘I’m no bloody hero’, says one. ‘I never want to set eyes on it again’, says another, asking, ‘What did we get out of it? It was a sad affair, the whole Anzac business.’

Masters’ starting point is that the Gallipoli story is more familiar to most Australians than Afghanistan. He is walked through the Australian War Memorial by its Director, Brendan Nelson, who points out how close the new Afghanistan room is to the World War I displays. It’s less about war, he says, offering the new linkage, than about friendship and love.

Masters then interviews James Brown, ex-Army, now at the University of Sydney via the Lowy Institute, about the differences between the two wars. Compared with the books and films about eight months at Gallipoli, says Brown, there’s almost no narrative about Australia’s 14 years in Afghanistan. Ben Quilty’s paintings loom over the Afghanistan display at the War Memorial, but no official war correspondent was sent to Afghanistan. As a result, says a veteran, ‘people at home don’t understand what it’s like – the media talk about deaths and injuries, not about our successes’.

Gallipoli wouldn’t happen today, say the new generation of soldiers: running into gunfire was rash, lost much and gained little. The modern battlefield is more dangerous, with ‘360 degree risks’, making troops rely on each other more. When an army cook was killed in a ‘green on blue’ attack, says his former senior officer, it made many doubt their purpose for being there, although he wouldn’t let himself ‘fall into the trap of saying our time there was wasted’. An officer of the Royal Australian Engineers, however, says that. just as the World War I Diggers came back with broken hearts, what she saw in Afghanistan and Africa ‘broke her heart’.

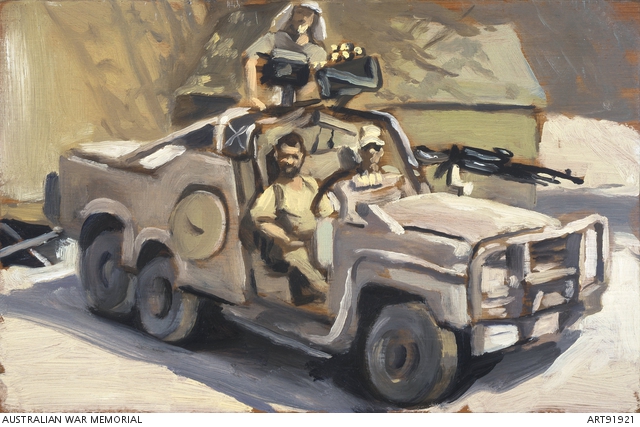

Three SAS guys sitting in their vehicle, Australian compound, Bagram, Afghanistan, September 2002 (Australian War Memorial ART 91921/Peter Churcher; unchanged)

Three SAS guys sitting in their vehicle, Australian compound, Bagram, Afghanistan, September 2002 (Australian War Memorial ART 91921/Peter Churcher; unchanged)

Brendan Nelson says the modern Australian armed forces see themselves as aid workers, teachers, first aid providers, mentors, anthropologists and diplomats. These responsibilities fall to all of them in Special Operations. (That must be why they have diplomatic passports in Iraq now.) Masters goes unquestioningly along with this fantasy, telling viewers that Australia’s modern mission in war is to keep the peace (sic) and navigate the cultural chasm. That requires moral and physical courage, an ex-officer in Afghanistan says: ‘One day they say g’day, the next they blow you up’. The enemy is determined, and ‘they’re actually very organised’, using innovative techniques to communicate the Australians’ movements. (He doesn’t fall into the trap of asking why they would want to do that.)

It was the United States alliance that drew Australia into Afghanistan, says another, and the Americans were brave, helpful, and ready to provide medical evacuations. ‘We get along with everybody’, says another ex-officer. (Who is everybody?)

If Afghanistan ‘has yet to gain public engagement’, as Brown argues, is that because it lacks a Beanist myth-maker, or because of a fundamental conundrum about why we were there? Even the old Diggers, one of them says, weren’t at Gallipoli ‘for King and country’. Every war, an Afghanistan veteran tells Masters, is at first about right and wrong, but eventually that gets confused. In both Gallipoli and Afghanistan, the ex-soldiers agree, survival was often a matter of luck. Some still alive tell Masters they feel luck’s running out.

‘Broken bodies and broken hearts’, Kerry O’Brien soliloquises at the end of Four Corners, offering hotline numbers for people contemplating suicide. What about not doing it all again?

Alison Broinowski is Honest History’s vice president

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.