(Australian Electoral Commission)

(Australian Electoral Commission)

As the election is announced, complete with warlike metaphors, it is timely to look at some other slices of our history, past and present, where war is rather more real or more possible. (Honest History will probably not be attempting election commentary over the next 56 days, except when there is something of clear historical interest. Everyone doesn’t have to be a critic, after all.)

War powers

Honest History’s vice president, Alison Broinowski, writes in John Menadue’s Pearls and Irritations blog about how Australian governments of both sides eschew constraints on their ability to go to war without reference to Parliament.

When democratic processes are bypassed, the restraints of international and domestic legality are overridden. When accountability for war and its outcomes is not shared with the people’s representatives, the executive can do as it pleases, can withhold from the public the details of what is being done in their name, and can repeat its past errors with impunity.

Broinowski notes there have recently been setbacks in the United Kingdom and the United States to democratic accountability in war waging. As for Australia, Henry Reynolds’ recent book, Unnecessary Wars, shows how our governments ‘find it easy to go to war’. It has been that way since 1885; all that has changed has been the identity of the empire doing the bidding and to whom we have been eager to hitch ourselves.

Leaving Afghanistan

Alison Broinowski also cites reports that Afghani troops are pulling back from Uruzgan province, where Australians were previously based and with which they came to identify. The reports, she says, aroused little interest in Australia, despite the ‘Lest We Forget’ trope routinely applied to our wars. The lack of interest underlines that such involvements are less about making a difference to the country concerned than about playing our Australian role as what former US president Lyndon Johnson thought of as ‘the next large rectangular state beyond El Paso’.

Uruzgan is not Australia’s province [Broinowski says]. It can no more be claimed as uniquely Australian than Nui Dat or Kapyong, the Kokoda track or Gallipoli could. As the junior ally of Britain and the United States, our troops have always gone where they tell us to go, fought who they tell us to fight, and left when they leave (with the honourable exceptions of Curtin bringing Australian forces back to defend Australia in 1942 and Whitlam pulling them out of Vietnam in 1972).

The history of Afghanistan is always instructive, as we said in September 2013, following William Dalrymple. Britain’s nineteenth century involvement in Afghanistan has been called ‘the worst British military disaster until the fall of Singapore, exactly a century later’. Australia’s long swing through Afghanistan was not in the same league but should offer lessons nevertheless. A report from 2015 on problems in Uruzgan.

Above (and around) us the waves

Turning to wars that might (or might never) be, Honest History has regularly noted the sparring in the South China Sea, into which Australia seems keen to paddle. Australian barrister and commentator James O’Neill, has published a piece (in the Moscow-based New Eastern Outlook) on that set of issues.

Australia has joined the United States and others in conducting military exercises in the South China Sea. There is no plausible military threat to Australia, yet it has joined in what are clearly provocations aimed at the PRC … The current involvement of the Australian Navy in joint exercises with the Americans in the South China Sea is a further illustration of taking steps that are inconsistent with Australia’s national interests, but acquiescing yet again to another American “request” … Both Australia and China have an interest in a stable and prosperous Asia. For Australia to be a significant contributor to, and beneficiary of, that stability and prosperity it needs a fundamental rethinking of its geopolitical priorities. The signs for such a necessary rethinking however, are not promising.

(A later piece by O’Neill.) On Pearls and Irritations also, Richard Broinowski questions why Australia is buying French submarines and wonders why we should seek interoperability only with the United States and not with regional countries. Jon Stanford has a different view, detecting an apparent desire in some Australian quarters for an independent Australian ‘power projection’ capacity (that is, to unilaterally take other countries on) but Stanford and Michael Keating still believe the submarines decision is wrong for a variety of reasons.

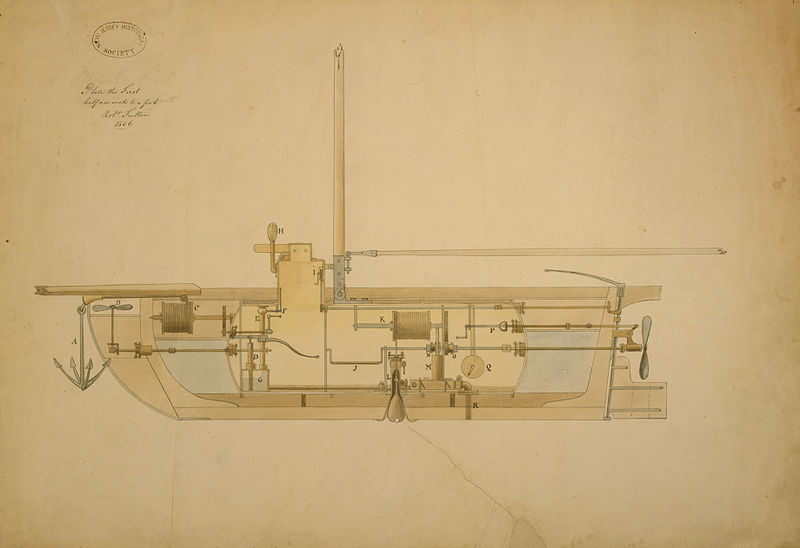

Robert Fulton design for submarine, 1806 (Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress)

Robert Fulton design for submarine, 1806 (Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress)

Finally, Fairfax’s Paul Malone makes a crucial point, pointing out that the submarines ‘are likely to be obsolete by the time they are launched. By 2030 China will undoubtedly have underwater acoustic devices and drones deployed in the region to detect military intruders.’ It makes one wonder why we are bothering, really. In similar vein, James O’Neill, commenting on Stanford’s piece, describes

the Chinese Dongfeng-41 ICBM that will travel between the PRC and Australia in about 30 minutes. Its multiple warheads would wipe out such military and civilian assets as we have in short order. Our war with China would be over very quickly.

Honest History’s earlier material on the submarines decision in historical context, here (scroll down) and here (again, scroll down). A different, supportive view on the desirability of the submarines, from Alistair Cooper in Fairfax.

A horse, a horse!

As for fighting the last war, as we may well be doing with the submarines, there is the horsey and ever hopeful Douglas Haig, generalissimo of the Great War and author of Cavalry Studies: Strategical and Tactical (1907), as documented by Adam Hochschild in To End All Wars (2011; Kindle locations 3152-55, 6197).

Shortly after taking command [in late 1915 of the British forces on the Western Front], Haig urged renewed cavalry recruiting and ordered a fresh round of inspections of his five cavalry divisions, to put spine into “some officers who think that Cavalry are no longer required!!!” In a letter to the chief of the Imperial General Staff, he spoke of being prepared for a version of Murat’s famous cavalry pursuit of the retreating Prussians at the Battle of Jena – in 1806.

The cavalry lance remained an official combat weapon of the British Army until 1928, the same year that Douglas Haig went to the great stable in the sky.

Postscript

The political historian, Morton Keller, reckons that the American Civil War left a legacy of ‘a series of military metaphors applied to party politics: political campaigns, party standard bearers, rank and file, precinct captains, and the like’: America’s Three Regimes (2007), referred to by Francis Fukuyama, Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy, Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, New York, 2015, p. 145.

8 May 2016