‘That faraway experience: some thoughts on family history and the Western Front’, Honest History, 7 October 2014

I had an uncle, John Holmes Wherry, my mother’s eldest brother in a family of six, who fought on the Western Front in 1918 with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. He was always known to the family as ‘Jack’, an echo of what I regard as one of the finest evocations of family memory in Australia about the First World War, the ‘Great War’. It comes from George Johnston’s My Brother Jack, a book taught in those dark days of the 1970s, when I was a teacher of School Certificate English classes in New South Wales.

In the first chapter of My Brother Jack the book’s fictional hero David Meredith – really a semi-autobiographical stand-in for Johnston himself – describes his gradual discovery as a child of the war experiences of his parents, both of whom were in the AIF. Father was a soldier at the ‘Front’, his mother a nurse in Europe, and then back home in Melbourne. Davy Meredith’s knowledge of the war comes not only from the psychologically and physically battered veterans who move in and out of his boyhood home, but also from the souvenirs and personal objects concealed in a ‘big, deep drawer’ beneath his parents’ wardrobe, objects redolent of what he calls ‘that faraway experience which had moved in behind the privet hedge to occupy every room and every cranny of our mundane little house’.

George Johnston, My Brother Jack, cover of first edition, 1964, with illustration by Sidney Nolan (digplanet)

George Johnston, My Brother Jack, cover of first edition, 1964, with illustration by Sidney Nolan (digplanet)

That experience was, of course, the reality of the war. It came home to Davy finally when he encountered the wartime portrait images of soldiers in a broken-down photographic studio window ‘full of dust, dead flies and cockroaches’. Before enlistees sailed overseas, thousands of such portraits were executed in Australia, most famously by the Darge Photographic Company of Melbourne at places like the Broadmeadows Camp. A search on the Australian War Memorial’s photographs on line for Darge brings up 18 581 results, some indication of the huge number of such photographs that must have been taken around Australia in each capital city by various studios, not to mention the country towns. Sometimes these pictures show the whole family, proud of their soldier son, brother, lover or boyfriend.

Nearly two generations later, in 1983, poet Peter Kocan tried to capture the significance of those photographs to the generation, like Davy Meredith’s parents, which was enveloped by memory of that ‘Great War’:

Sometimes in the homes of the elderly

Among the shabby, cherished possessions

You will find a framed photograph

Of a young man in quaint uniform

In Kocan’s poem this became ‘my brother Jim’ who ‘went to war … and didn’t come home’:

Now in a musty room somewhere,

An old person makes a cup of tea

And a not-yet-anonymous soldier

Stares out of the photograph.

For Davy Meredith that encounter was with just such images, spotted and fading, boys in AIF uniform with Rising Sun badges taken before they went on the great adventure. A callous, passing youth says to him as he stares in the window, ‘All them blokes in there is dead, ye know’. Suddenly, he had real men to link to one of those contents of his parent’s bottom drawer, images in copies of the Illustrated War News.

‘Here was that treeless, shell-torn wilderness of mud and barbed wire and duckboards and craters and broken artillery wheels and abandoned ammunition boxes that had been the Somme.’ This was the world of those wounded waifs and strays of war befriended by Davy’s compassionate mother, the nurse who knew the lasting effects of those places on the men who had fought there: ‘Bert sobbing in the back yard and Gabby Dixon’s face at the dark end of a room and the smell of chloroform in corridors and the bronchial cough of my father going off in the dawn light to the tramways depot’.

If we have an ancestor who fought on the Western Front how can we – even more removed as we are from the presence of that ‘faraway place’ encountered by the young Davy Meredith – how can we understand what those ancestors thought it was all about or what the experience was like or meant to them?

There are perhaps a number of approaches to that question, encapsulated in descriptions such as ‘military history’, ‘social history’ and ‘family history’. There are those, whose knowledge of the purely military side of things is great, but who like to distance themselves from such seemingly cold and operational words like ‘military history’ and prefer to see themselves as ‘social historians of war’.

There is also, of recent decades, something we might like to call ‘commemorative history’, the story not of the war itself and how it was fought so much as of how societies have set about remembering the conflict in ceremony, personal and societal, and the building of cemeteries and memorials. There is also the contribution of literary historians and many others, who have analysed the manner in which the experience of the Western Front was turned into poetry, music, theatre, art and, ultimately, television.

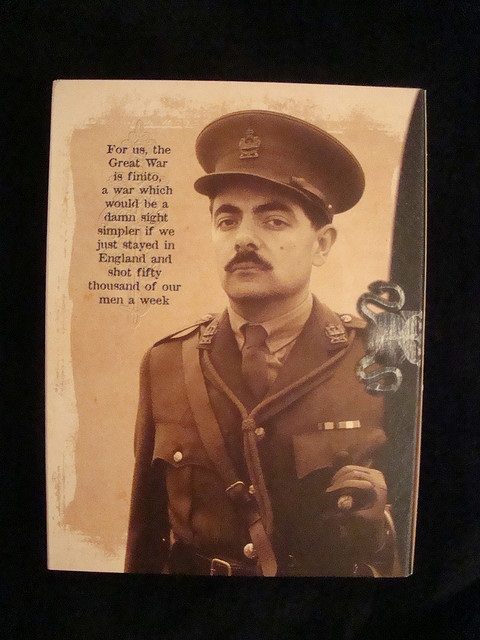

Illustration featuring Rowan Atkinson from DVD cover, Blackadder: Complete Collection (Flickr Commons/Humorblog)

Illustration featuring Rowan Atkinson from DVD cover, Blackadder: Complete Collection (Flickr Commons/Humorblog)

There is an argument that the most influential understandings we have of what the Western Front was all about have been supplied by shows which still get an airing, like the BBC’s Blackadder Goes Forth. In the final episode of that comedy series, where British generalship was lampooned ad nauseam, our anti-heroes – Captain Edmund Blackadder, Lieutenant the Honourable Colthurst St Barleigh, Captain Kevin Darling and ‘everyman’, Private S. Baldrick – line up in the trench before going ‘over the top’. Notably absent is General Sir Anthony Cecil Hogmanay Melchet KCB but repartee is sustained to the last witticism.

As the attack is about to go in, the guns fall silent. This is immediately and hopefully interpreted as the end of the war – peace has broken out. Blackadder brings his comrades back to bleak reality: ‘I’m afraid not. The guns have stopped because we’re about to attack. Not even our generals are mad enough to shell their own men. They think it’s far more sporting to let the Germans do it.’

Blackadder wishes them all good luck and they rush from the trench into the German machine guns. At this point the series, which has taken us through laugh after laugh, turns deadly serious. All of them are killed and the battlefield disappears, as a field of poppies, for remembrance, fills the screen. The message of Blackadder Goes Forth, witty and well-performed, seems to be that the war was a ghastly mistake in which millions became victims, sacrificed by a callous, class-ridden military machine.

Is this how your AIF soldier ancestors thought about it? That is a big question. Let’s look at one source – can we call it a military history source? – for some sort of perspective on that, the battalion history, published in 1934, of the 39th Australian Infantry Battalion.

Between 7 and 14 June 1917 this Victorian unit participated in the fighting during which Australian, New Zealand and British soldiers took, and then consolidated, the German line at Mesen (Messines) south of Ieper (Ypres). In that week alone, the 3rd Australian Division suffered 4107 battle casualties, of which 296 were in the 39th Battalion. Such losses, killed and wounded, seem almost obscene to us today when one death in combat is a national, front-page disaster. That is our perspective: what did the historian of the 39th Battalion, writing in 1934, 18 years after the battle, make of Messines and of the war itself?

The action for him had two phases: the horror of the approach march, followed by success in the field. As the Australians came up during the night of 6/7 June 1917 the Germans drenched them with gas shells:

[F]rom the beginning of the march men had to wear their respirators. The night was dark and calm and the gas hung about like a heavy fog … [M]en groped their way along the narrow tracks, frequently falling over unseen obstacles into ditches and shell holes and often losing the gas masks from their faces … That difficult march to the trenches was nothing short of a nightmare. Scores of men were falling out gassed, or wounded by the flying shell splinters. The gas shells poured into Ploegsteert Wood and burst with low reports and “pops”.

In the course of a long life, in school, university or from general reading have you not already encountered this scene, and had it interpreted for you?

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! –

An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And floundering like a man in fire or lime.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, –

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.

The Latin, from Horace, translates ‘How sweet and honourable to die for one’s country’. We are no longer quite so convinced of that. By the 1960s, certainly the 1970s, those famous lines of the English soldier poet, Wilfred Owen, and the lines of other ‘war poets’, were the First World War. Literature, to an extent, replaced the more dispassionate sources-driven approach of the historian.

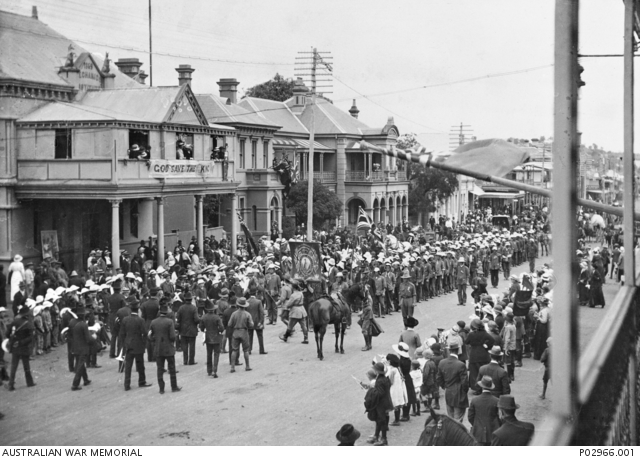

The Kangaroos recruiting march, Yass NSW, c. 1915 (Australian War Memorial P02966.001)

The Kangaroos recruiting march, Yass NSW, c. 1915 (Australian War Memorial P02966.001)

However, there are layers operating here. War, says Owen, is simply barbaric and his skill is in showing us just how barbaric it is. The 39th Battalion historian would not have disagreed but if we follow him onwards from the gas-impregnated environs of Ploegsteert Wood on the night of 6/7 June 1917 we enter a different scene. Leaders, such as Captain Alex Paterson, emerge from the chaos, rally the survivors and go on to capture all their objectives. The battalion’s two days in action were summed up like this:

The men of the battalion had borne themselves magnificently throughout the operation and carried on gallantly and uncomplainingly despite the large number of casualties which had entailed much additional hardship and strain. They had greatly distinguished themselves and had responded to all demands.

Now that was the view from 1934 but it has the merit of being the reflections of those involved not so long after the war. In any rounded view of what battle meant to an AIF ancestor such views, as reflected in a unit history, deserve consideration.

Unit historians were keenly aware of the personal costs of the war. Countless letters would have been written home from the battle areas to anxious relatives in Australia describing how someone had met their end or withstood wounds. They rarely saw their comrades, at least publicly, as having died for nothing. The 39th Battalion history, like most of these unit histories, carries the names of the 421 men of the unit who, in the great majority of cases, were killed in action or died of wounds. What had they achieved? Our 39th Battalion historian was in little doubt about that.

Many an unmarked spot in France must be forever Australia. The youth and flower of Australia’s manhood died valiantly fighting for their country and, by their sacrifices, laid the foundations of a Nation.

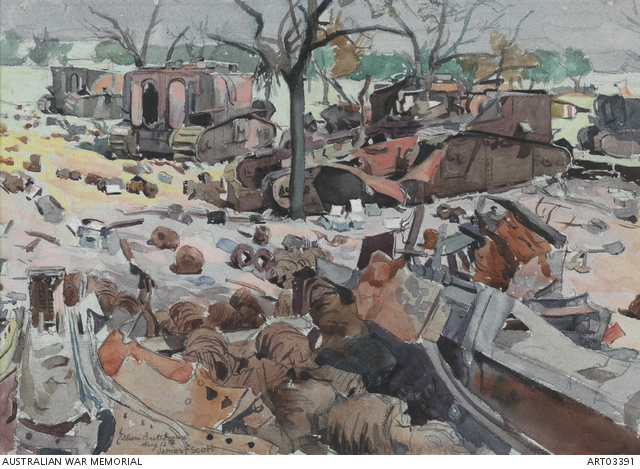

JF Scott, Wrecked tanks, Villers-Bretonneux, August 1918 (Australian War Memorial, ART03391)

JF Scott, Wrecked tanks, Villers-Bretonneux, August 1918 (Australian War Memorial, ART03391)

Today, that seems to many commentators an over-simplification, almost naïve and simply wrong. Modern Australia, many argue, was not born on the shores of Gallipoli or the battlefields of France and Belgium but as the result of many other complex and multi-faceted historical pressures and experiences. We might agree with that while also giving ear to both our 39th Battalion writer and Wilfred Owen.

And there are of course heaps of other readily available sources to consult – official war diaries, official photographs (especially those of men like Frank Hurley and Hubert Wilkins on the Western Front), official and unofficial histories, the list is endless. Giving space to all of it helps to widen continuously our frames for reference for approaching something so vast, so terrible and so monumental as even little Australia’s experience of the Western Front.

And a word like ‘monumental’ leads to a consideration of commemoration, of commemorative history, of families and individuals remembering. Here we are confronted by the loss of war, by the grief it causes, by the gaps it tears in the lives of individuals, families and whole societies. The Western Front, in this context, was, and remains, Australia’s great location of loss, 46 000 men out of a national tally, as presented on the walls of the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial, of more than 102 000 names. In other words, all that time ago two years and seven months of battle produced virtually 46 per cent of the nation’s war deaths.

Over the next four years we enter a period which some commentators see as one that will be marked by an over-abundance of official commemoration of those now far away events, and where their supposed central significance to Australia will be driven home at many official, large-scale public commemorative occasions. This is not the place to engage in an argument about whether all this is appropriate or proportionate, but it is interesting to note how one aspect of Australian commemoration of the ‘Great War’ has evolved over the last decade or so.

Take Villers-Bretonneux in France, the site of Australia’s National Memorial on the Western Front. I first went there in 1982, on a cold November day with no one else about, and was greatly moved by a personal, hand-written entry in the visitor’s book. A lady from Adelaide had visited two days before and wrote that she had made this journey for her mother who had never been able to come. One sensed that perhaps somewhere in that large cemetery was the grave of an uncle, a grandfather, a cousin or maybe even a fiancé who never came home. His name might have been among the 11 000 Australian names on the memorial to the missing. Reading this, in the cold and gloom, was like approaching that writer’s mother’s inner sanctum of grief and loss, one that she may well have survived in fine fettle, but which never entirely left her.

For many years the people of Villers-Bretonneux held a small Anzac Day service here to honour the dead and to remember that among them were soldiers, predominantly although not exclusively Australian, who had recaptured their town from the Germans on 25 April 1918. Australian ambassadors from Paris would attend this simple and locally-driven event.

Lawrence Howie, Villers-Bretonneux, 1919 (Australian War Memorial ART 93084)

Lawrence Howie, Villers-Bretonneux, 1919 (Australian War Memorial ART 93084)

Slowly, the numbers of Australian visitors to the Western Front grew until finally government was virtually forced to take over what was to happen, what was to be said and done, at the Australian National Memorial on Anzac Day. This has become a sizable event to be managed, one where the locals now get, officially, to lay a couple of wreaths and where the suits and beribboned uniforms of the military of Australia and France are very much in evidence. Songs, many of the World War II variety, entertain the waiting crowd; huge faces of dead soldiers are projected on to the memorial tower; catafalque parties are mounted; speeches are made full of the expected and acceptable rhetoric of national concern for appropriate remembrance; the beribboned and suited lay official wreaths; a bugle sounds the Last Post; catafalque parties are dismounted; and, finally, individual tributes and wreathes are invited and laid.

Somewhere, we can imagine, among those personal tributes is one from that lady in Adelaide who went there quietly all those years ago to fulfill, in her words, a ‘wish of my mother’. We have no way of knowing how those mighty dead of the AIF, whose names and graves surround the scene, would react to all this contemporary, concentrated commemorative effort. It is a far cry from the Anzac Days their comrades would have observed as they grew old and age condemned them.

Today’s modern ceremonies have little to tell us about past remembrance, about the feelings of the generations who actually experienced the war, experienced its real, not imagined or digitally-recreated loss. To get at what that might have been like, to have any chance of understanding them, we have to stand, I feel, somewhere different, away from the bright lights and carefully constructed sentiment of a modern Anzac event.

But a word of caution. American historian of the uses and misuses of history and heritage, David Lowenthal, warns us, ‘The past is a foreign country’. Those words are the opening lines of LP Hartley’s novel, The Go-Between, from which Lowenthal grabbed the thought and took the idea further: ‘The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.’

We can never really visit the past, never fully, perhaps even in any but a small way, sense what it was like to be inside the mind of an ancestor. We need to be more than careful of ascribing to them our own sentiments, judgments and feelings as if they are simply another version of us.

Where then to look for the impact of the loss visited on Australian families by that huge blood- letting on the Western Front? To hear its echoes you don’t need to move much beyond two great national collections housed here in Canberra at the Australian War Memorial and in the National Archives of Australia.

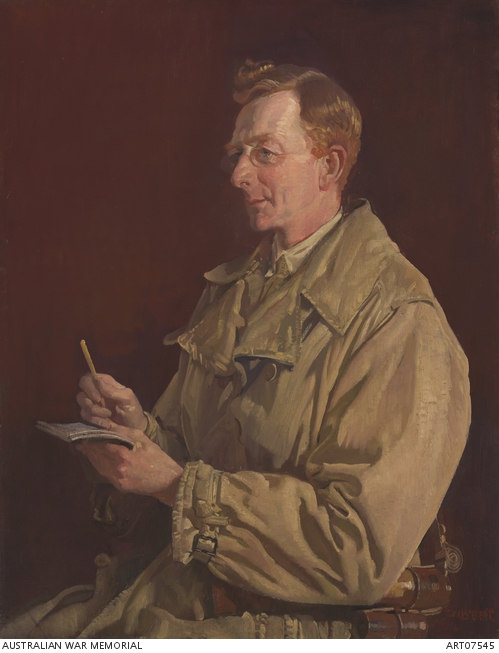

GW Lambert, Charles EW Bean 1924 (Australian War Memorial ART07545)

GW Lambert, Charles EW Bean 1924 (Australian War Memorial ART07545)

The Roll of Honour Circulars at the Memorial were devised in the 1920s for Charles Bean as he wrote away at his mammoth history of the AIF. He wanted to know about those who had died and he wanted to know it from their next of kin, their families. What had they to tell him about the one who would never return and with what suburb, district or town would they like his name to be recorded on the national Roll of Honour at the proposed ‘Australian War Memorial’.

In a hundred years, Bean argued, nobody beyond those engaged in something we now call ‘military history’ would have a clue about what units such as the First Light Trench Mortar Battery, let alone the First Battalion, were all about. Anyway, as Bean asserted – and he was in a better position than most in his generation to know – the AIF was ‘incorrigibly civilian’ and would have appreciated the fact that the names of their dead comrades were to appear on the roll under place names like ‘Yass, New South Wales’. This, Bean felt, returned to them their identity as ordinary Australians from somewhere people could relate to.

Young Clem McGrath was from Euralie, a dot on the map near Yass, and he was among the first handful of Australians to die on the Western Front in trenches south of Armentieres in April 1916. He received a gunshot wound to the head on 15 April and died later that day. To find something of the context of his death we can consult the war diaries of the 2nd Australian Division, the 5th Australian Infantry Brigade and, finally, the 18th Australian Infantry Battalion for the date of Clem’s death, 15 April 1916. Bean has also much to say about these early months of Australian experience in France in The AIF in France, 1916, Volume 3 of the Official History of Australia in the War.

Mary McGrath, aged 5, sister of Clem, unveils Euralie Public School Honour Roll, 19 July 1918 (Yass Remembers)

Mary McGrath, aged 5, sister of Clem, unveils Euralie Public School Honour Roll, 19 July 1918 (Yass Remembers)

To sense something of Clem’s family’s reaction, however, we can imagine them, sometime in the mid 1920s sitting down in their house at Euralie, near Yass, to fill in the Roll of Honour Circular that has just arrived from Melbourne. The handwriting is almost certainly that of Clem’s father, John McGrath. He crosses out the word ‘killed’ on the form leaving the word ‘wounded’ because what he writes next is where he has been informed that Clem received the wound which hours later led to his death – somewhere called ‘Bois Granier’. This is the little village of Bois Grenier not far from another location well known to us today, Fromelles.

There is not much else John wants to tell the official historian: Clem was a farmer; he was 20 years and four months old when he died; and he attended the Euralie Public School. Oh, and his name should be listed on the proposed national memorial under ‘Yass’.

Like no other document now in public hands the Honour Roll Circular takes us into the intimate personal world of the McGrath home as they struggled with what final words to write about Clem. Reading it we can sense for the McGraths the reality of the Western Front, in Davy Meredith’s words, ‘that faraway experience which had moved in behind the privet hedge to occupy every room and every cranny of our mundane little house’.

Four other documents created in the McGrath household open a window into their personal world of loss. These are letters in Clem’s personal dossier, or service record, now in the National Archives of Australia and written over a period of eight years, 1916-24, each signed by his father, John McGrath, and each addressed from Euralie.

The letters are only short, being responses to the receipt of small packages and information about Clem from the so-called AIF ‘Base Records’ in Melbourne. The first, dated 21 August 1916, gives thanks to the Officer in Charge for letting them know where Clem was buried – Bailleul Communal Cemetery Extension. Such news, writes the father, ‘makes the loss less hard to bear’.

When Clem’s few personal possessions – identity disk, rosary beads, a coin, a prayer book, two notebooks and a horseshoe (Clem was described in another document in the dossier as a good horseman) – reached home in December of that year John describes them in a letter to Base Records as the ‘effects of my poor son’.

Four years pass and in 1920 the family receives a photograph of Clem’s grave, not the final Portland stone Imperial War Graves Commission headstone, but an earlier wooden cross marker in Bailleul Communal Cemetery Extension with small metal plaque carrying Clem’s name, rank, unit and date of death. ‘I can assure you’, wrote John, ‘we have not received anything we could prize more’.

A final letter to Base Records, in September 1924, thanks them for information that has been sent regarding Clem’s burial site, possibly an image of Clem’s permanent headstone: ‘It is most gratifying to know that the graves of our fallen soldiers are being so well attended to’. Gratitude, loss, small personal possessions, knowledge of burial, the careful tending of a grave and a photograph which would have been treasured and held tenderly for a lifetime; small things but the every stuff of personal remembrance, held more closely than those, doubtless worthy, national sentiments voiced in the large ceremonies of public recognition.

Euralie Public School Parents and Friends, Honour Roll unveiling, 19 July 1918 (Yass Remembers)

By coming closer to those small family things and documents we come closer to the lasting impact on individuals and families of somewhere called the ‘Western Front’. And what is not recorded in any official document is that the McGraths eventually called their home Bailleul. With Clem’s death the Western Front moved into ‘every cranny’ of Bailleul at Euralie.

It was in that fashion that I encountered Uncle Jack’s war on the ‘Western Front’. A few years ago I was at the end of a tour I was leading for Australians around the Western Front when we passed a town called St Quentin on our way back to Paris. Two days later, sitting doing research in the Public Record Office in Kew in London, I realised that here was a collection that held the service record of Second Lieutenant John Holmes Wherry of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. Most of the documents in it were of the expected administrative type but of a sudden I was confronted with a lengthy piece in his own hand, a handwriting I had never seen but which was the spitting image of my mother’s writing.

Before me was someone I never met – for he died before I was born – the eldest son, my mother’s much loved brother, someone she called a ‘lady’s man’, handsome, wild. Enlisting as soon as he turned 18 in 1916 he terrified my grandmother, confronted as she was by the huge casualty lists emanating from the Battle of the Somme – more than 5000 men of the 36th Ulster Division killed or wounded in one day, 1 July 1916. And Jack was destined for one of those infantry units that made up that division.

This document, never before seen, I suspect, by anyone else in the family, was written in 1919 after Jack’s return from a German prison camp. It was written in the hotel in Dungannon, County Tyrone, run by his parents. It described his capture by the enemy on 21 March 1918 at a place called Grugies, a name with which I was, astonishingly, familiar as it was the suburb of St Quentin through which I had passed barely 48 hours before.

There is a lot to unpack, militarily, from this document but what brought tears to my eyes was something else entirely. Jack died fairly young, aged 48, and my mother always told me this was due to his heart-lung system having been badly affected by gas inhaled on the Western Front. Indeed, she used to describe him as having been ‘slightly gassed’. There was that very phrase, in Jack’s own hand, on this long-hidden document. He died in May 1944 near London but was brought home for burial in his mother’s ancestral plot in Tullybranigan cemetery beneath the Mountains of Mourne in County Down. For years, for some reason, I thought he died in 1943 but when I read the date of death on his grave I knew, with a shock, that I had attended his funeral in embryo as it were, for I emerged into the world just seven months later.

‘Slightly gassed’. Was this not how the Western Front, Davy Meredith’s ‘faraway experience which had moved in behind the privet hedge to occupy every room and every cranny of our mundane little house’, laid its hand upon my own family? I have never seen a photograph of Jack. My only personal encounter with him has been my reading of that document in his dossier. When the time comes on 21 March 2018, one hundred years since Jack was gassed, I will remember him.

Richard Reid gives us a characteristically rich meditation on remembrance, one informed by his many years as a public historian, especially of the Great War: thank you.

I wondered about one passage, though: “Slowly, the numbers of Australian visitors to the Western Front grew until finally government was virtually forced to take over what was to happen, what was to be said and done, at the Australian National Memorial on Anzac Day.”

Why “virtually forced to”? Wouldn’t it be true to say “the Australian government decided to take over” the Villers-Bretonneux ceremony? Why could it not have remained a local commemoration? Why did it need to be ‘managed’ by DVA?

Because surely the fact is that while traffic and toilets may have demanded a greater co-ordination, the fact was that the ceremony has been entirely appropriated by the official agenda. Given the ‘organic’ way the ceremony developed, that official take-over is (in my view) sad – but entirely representative of how the idea of Anzac has become ‘managed’ by official bodies.

Peter Stanley