‘Two uncles, two great-uncles, two wars: a family Anzac story’, Honest History, 25 April 2023

For most families who are directly affected by war, commemoration is not speeches by politicians, not parades and wreaths and children waving flags; instead, it is something families live every day and every week, forever and down through the generations. It is the reparations that families pay for the decisions that governments make to send men and women to war. (David Stephens, The Honest History Book, 2017)

This is a family story about my Uncle Cam, his two uncles, both called Syd or Sid, who were my great-uncles, and my uncle Hec. I never knew any of them. Each of them died in a war.

Captain Sydney James Campbell, 8th Light Horse, 1882-1915

Syd grew up in Portland, Victoria, went to Geelong Grammar, then to the University of Melbourne, where he graduated as a doctor and became a tutor at Ormond College. He came from a well-off family. His father, Hugh John Munro (‘Papa’) Campbell, had prospered as the owner of a general store in Portland. From 1895, the family lived in a mansion, ‘Maretimo‘, just out of town, built in around 1856 by John McLeod, who had hoped it would become Government House when Portland became the capital of the colony of Victoria.

Syd had three sisters, Hettie, Chrissie and Queenie, and a brother, Hugh Munro, my grandfather. The picture shows the extended family (and servants) on the steps of Maretimo in about 1910. Syd is third from left in the back row; Hugh is in the back row also, on the right. (Maretimo is still there today.) Papa Campbell had been elected to the State Parliament in 1906 in the seat of Glenelg. He was a Nationalist, or conservative.

The war came and Syd enlisted. He was commissioned and appointed Medical Officer to the 8th Light Horse Regiment. He left Melbourne in February 1915, arrived in Egypt, then landed at Gallipoli on 20 May 1915. The picture was taken just after he gained his commission. By all accounts, he was well-liked in the regiment, by officers and men, and was a good doctor under trying circumstances. Some spelled his name ‘Sid’.

The war came and Syd enlisted. He was commissioned and appointed Medical Officer to the 8th Light Horse Regiment. He left Melbourne in February 1915, arrived in Egypt, then landed at Gallipoli on 20 May 1915. The picture was taken just after he gained his commission. By all accounts, he was well-liked in the regiment, by officers and men, and was a good doctor under trying circumstances. Some spelled his name ‘Sid’.

It was a hot summer, that July 1915, and Syd and other officers often swam in the evenings in Anzac Cove, which is shown here at about that time. They jumped and dived off the pontoons and barges, even though there were often bullets and shells flying around. (Readers may recall a scene from the movie, Gallipoli, with blood in the water.)

This happened on 14 July 1915:

They undressed on a barge and were just ready to go into the sea … An 8-inch shell came along and caught Sid sideways on, cutting off both legs below the knee … He was conscious for a few seconds and gave the stretcher-bearers instructions as to tying him up.

That was from a letter to Papa Campbell from Syd’s best friend, Mervyn Higgins. Syd died about one o’clock the next morning on the hospital ship Sicilia and was buried at sea in Anzac Cove. He was two weeks short of his 28th birthday. (Mervyn Higgins was the son of Mr Justice Henry Bournes Higgins of Harvester Judgement fame. Mervyn was killed in Syria in December 1916.)

The commanding officer of the 8th Light Horse, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander White, wrote to his wife: ‘A sad, sad, day, poor dear Campbell, how we all loved him. The best and most honoured of men. Doctor, soldier, gentleman, friend, how I shall miss him.’ White himself was killed a month later at the Battle of the Nek.

What happened next? Because his father was a member of the Victorian Parliament and an Honorary Minister, news of Syd’s death went from the Defence Department in Melbourne to Sir Alexander Peacock, Premier of Victoria, who broke the news to Papa.

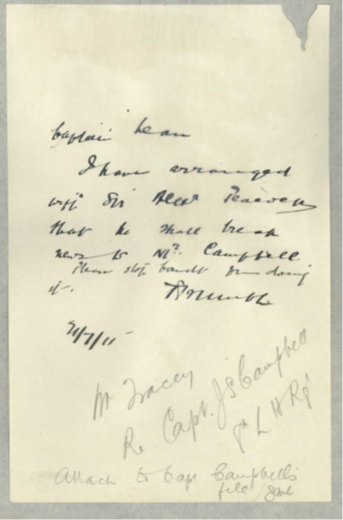

This page is from Syd’s war record and shows an official (signature illegible but probably someone in Sir Alexander’s office). The words read: ‘Captain Lean: I have arranged with Sir Alexander Peacock that he shall break news to Mr Campbell. Please stop Minister from doing this. [illegible] 21/7/1915’. (Captain Lean was in charge of Base Records at Victoria Barracks. The Minister who was being kept out of the loop was the Defence Minister, Senator George Pearce.)

This page is from Syd’s war record and shows an official (signature illegible but probably someone in Sir Alexander’s office). The words read: ‘Captain Lean: I have arranged with Sir Alexander Peacock that he shall break news to Mr Campbell. Please stop Minister from doing this. [illegible] 21/7/1915’. (Captain Lean was in charge of Base Records at Victoria Barracks. The Minister who was being kept out of the loop was the Defence Minister, Senator George Pearce.)

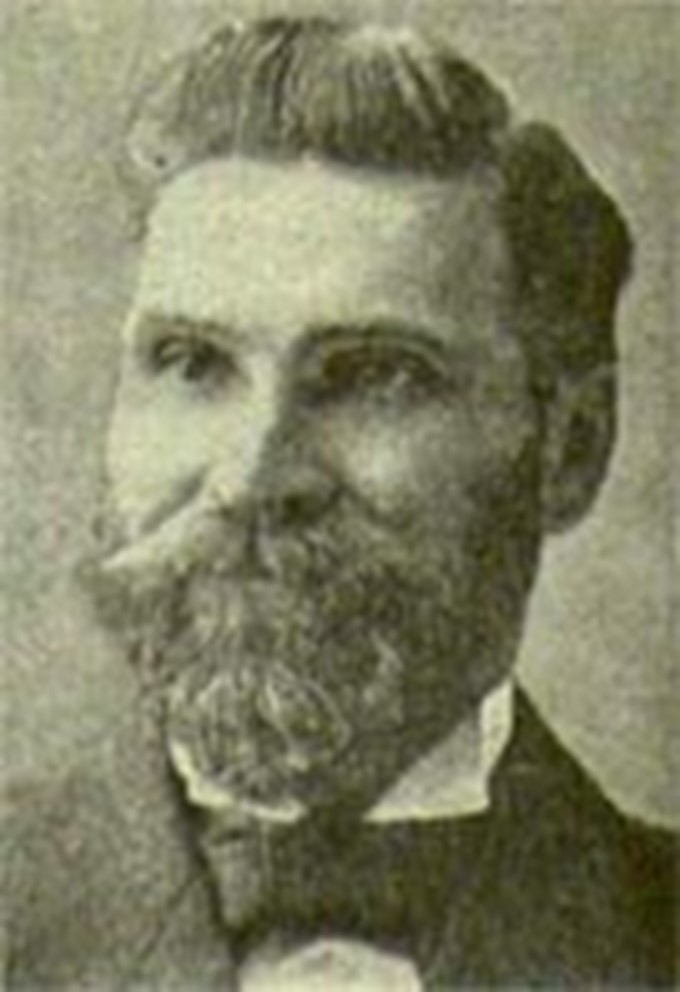

Here’s a picture of Papa Campbell, taken a little later than 1915. He looks sad, perhaps because his first wife, Harriet, had died in 1912, then Syd in 1915, then one daughter died of TB, then another daughter was committed to a mental asylum. Then, Papa lost his parliamentary seat in 1920, became seriously ill, married his nurse, Ethel Waddell, much to the chagrin of his family, failed to regain his seat in 1921 and died in the same year.

Along the way, Papa lost a lot of money when creditors failed to repay loans. The big house, Maretimo, had to be sold. My grandfather, Hugh, Syd’s older brother, had not gone to the war but stayed home to look after the family business. Around this time, he contracted an illness that stayed with him for decades.

Along the way, Papa lost a lot of money when creditors failed to repay loans. The big house, Maretimo, had to be sold. My grandfather, Hugh, Syd’s older brother, had not gone to the war but stayed home to look after the family business. Around this time, he contracted an illness that stayed with him for decades.

Despite Syd’s death, by late 1916 Papa was campaigning in support of conscription. That was not uncommon in families at that time, not just political ones. There may have been a feeling that one’s son or brother should ‘not die in vain’ and that it was important to make sure that others ‘do their bit’.

Corporal Sutton Henry (Sid) Ferrier, 10th Light Horse, 1877-1915

Another Sid here, full name Sutton Henry, one of eleven Ferriers from Casterton, Victoria. Sid is second from left in the back row of the picture below. Seven of these brothers and sisters lived into their 90s, including my grandmother, Ina, first on the left in the front row, who reached 96 years of age.

Another Sid here, full name Sutton Henry, one of eleven Ferriers from Casterton, Victoria. Sid is second from left in the back row of the picture below. Seven of these brothers and sisters lived into their 90s, including my grandmother, Ina, first on the left in the front row, who reached 96 years of age.

When there are six brothers there is the question: who inherits the farm? Sid was not the oldest, so he went to Western Australia in the early 1900s and worked on other people’s farms with horses, carts, and ploughs. (The photo is from when he made a visit back to the family property, ‘Ferry Hill’, in about 1910. More than a century later, the farmhouse is long gone.)

By the time the war came, Sid was back in WA, and he enlisted in the 10th Light Horse, reducing his age by a couple of years to avoid missing out. By May 1915, he was at Gallipoli, where he bumped into Syd Campbell, whom he knew from the family connection. (Sid Ferrier’s younger sister, Ina – my grandmother – had married Syd Campbell’s older brother, Hugh Munro – my grandfather.)

By the time the war came, Sid was back in WA, and he enlisted in the 10th Light Horse, reducing his age by a couple of years to avoid missing out. By May 1915, he was at Gallipoli, where he bumped into Syd Campbell, whom he knew from the family connection. (Sid Ferrier’s younger sister, Ina – my grandmother – had married Syd Campbell’s older brother, Hugh Munro – my grandfather.)

I mentioned The Nek, where Colonel White of the 8th Light Horse was killed. Readers might recall the final scene of the movie Gallipoli (the photo on the left). Mark Lee played a character based on Gresley Harper of Guildford, WA. Gresley was killed at The Nek.  Sid Ferrier survived The Nek but, three weeks later, 27 August 1915, he was at another small battle, Hill 60, with Australians, New Zealanders, and Ottomans within ten yards of each other, hurling bombs back and forth.

Sid Ferrier survived The Nek but, three weeks later, 27 August 1915, he was at another small battle, Hill 60, with Australians, New Zealanders, and Ottomans within ten yards of each other, hurling bombs back and forth.

Below is Hill 60 in 1919, along with one of the Ottoman Bombs. They were the size of a cricket ball, and had a metal handle attached when first thrown – but not when thrown back.  The idea was for the Anzacs to pick up the bombs as they landed and hurl them back before they exploded. Sid was a bit slow with one bomb; he had been playing cricket on the beach and had aggravated an old injury. His right arm was blown just about off. He walked down to the field dressing station, and they amputated his arm. The story told was that he wasn’t concerned about the arm but ‘I’d just darned the shirt’.

The idea was for the Anzacs to pick up the bombs as they landed and hurl them back before they exploded. Sid was a bit slow with one bomb; he had been playing cricket on the beach and had aggravated an old injury. His right arm was blown just about off. He walked down to the field dressing station, and they amputated his arm. The story told was that he wasn’t concerned about the arm but ‘I’d just darned the shirt’.

Sid was carried onto the hospital ship Devanha to go to England for treatment. He contracted tetanus – there was no penicillin in those days – died and was buried at sea off the coast of Portugal on 9 September. This is what was said about him. First, Chaplain Basil Bond, writing to Sid’s father, John, back in Casterton.

Sid was carried onto the hospital ship Devanha to go to England for treatment. He contracted tetanus – there was no penicillin in those days – died and was buried at sea off the coast of Portugal on 9 September. This is what was said about him. First, Chaplain Basil Bond, writing to Sid’s father, John, back in Casterton.

He did splendidly, and was so bright and cheerful – until a few days ago – and then tetanus set in and he died yesterday evening … His possessions included: Disc; Pay Book; Note Book and Letters; Pipe. Please accept my sincerest sympathy in this your sorrow and sacrifice. He died a hero and a Briton. May God comfort you in your sorrow.

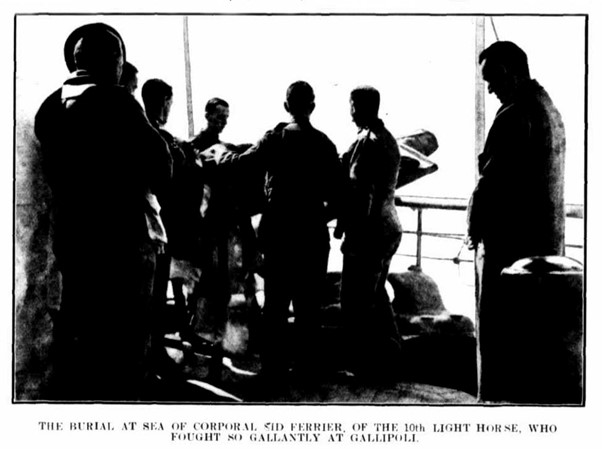

Then Sid’s Lieutenant, Hugo Throssell, writing to Sid’s mother, Alicia: ‘I saw him just half-an-hour before he died … He did not know me, but as I bent over the old chap the last word I heard him say was “Mother”.’ Here’s the picture of the burial. We’ll come back to it later.

These sorts of letters to families were quite typical; perhaps they were true in their references to last words and stoicism. Perhaps. Anyway, they were meant to provide comfort to families.

These sorts of letters to families were quite typical; perhaps they were true in their references to last words and stoicism. Perhaps. Anyway, they were meant to provide comfort to families.

Lance Corporal Hector Charles Stephens, 2/29th Battalion, 1912-1943

Now to the other side of my family, my uncle Hec, my father’s older brother. And another war.

Now to the other side of my family, my uncle Hec, my father’s older brother. And another war.

Here is Hec in his uniform in 1941. He grew up in Western Victoria, where his father, Thomas George (TG) owned a number of general stores. Hec lived mostly in Beeac, near Colac. There’s the Beeac store in the 1920s; the house was attached, just round the corner. (The store was still there in 2018, minus its verandah, and so was the house.)

Hec was one of nine surviving children out of 11 born. (His mother, Elizabeth, died of uterine cancer when Hec was 20.) Hec’s father, TG, was a lay preacher at the local Methodist church; he sometimes boasted that the choir was composed entirely of his own children. They could all sing, too.

Hec was one of nine surviving children out of 11 born. (His mother, Elizabeth, died of uterine cancer when Hec was 20.) Hec’s father, TG, was a lay preacher at the local Methodist church; he sometimes boasted that the choir was composed entirely of his own children. They could all sing, too.

Hec became a schoolteacher and in 1941 he began at a one teacher school at Mt Eccles South, in the hills near Leongatha, Gippsland. (It’s now a B & B.) Here he is with his pupils. He enlisted in mid-1941 and paid a farewell visit to TG at Beeac (picture below). By September 1941, he was in Singapore with the 2/29th Battalion, raw Australian soldiers sent there in anticipation of a Japanese attack.

Hec became a schoolteacher and in 1941 he began at a one teacher school at Mt Eccles South, in the hills near Leongatha, Gippsland. (It’s now a B & B.) Here he is with his pupils. He enlisted in mid-1941 and paid a farewell visit to TG at Beeac (picture below). By September 1941, he was in Singapore with the 2/29th Battalion, raw Australian soldiers sent there in anticipation of a Japanese attack.

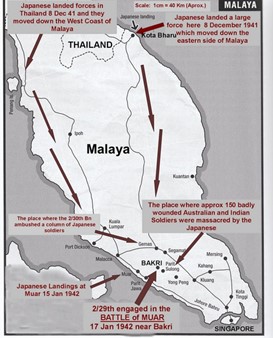

Some of the Australians filled in time by getting their faces turned into fake banknotes.  Then, it was Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and the Japanese came marching and bicycling down the Malayan Peninsula (map below). Those raw Australians in the 2/29th and 2/19th Battalions, along with some even less experienced Indians, as well as some British, were sent out to try to slow the Japanese advance.

Then, it was Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and the Japanese came marching and bicycling down the Malayan Peninsula (map below). Those raw Australians in the 2/29th and 2/19th Battalions, along with some even less experienced Indians, as well as some British, were sent out to try to slow the Japanese advance.

At the Battle of Muar, Johore (now Johor) State on 14-22 January 1942, bottom left of the map, there were 4000 men killed, including 3000 on the Allied side. In the 2/29th and 2/19th, more than 500 Australians died, about the same number as were killed in the Vietnam War. And Muar lasted for just a few days, where Vietnam went on for over ten years.

At the Battle of Muar, Johore (now Johor) State on 14-22 January 1942, bottom left of the map, there were 4000 men killed, including 3000 on the Allied side. In the 2/29th and 2/19th, more than 500 Australians died, about the same number as were killed in the Vietnam War. And Muar lasted for just a few days, where Vietnam went on for over ten years.

After Muar, there was the Parit Sulong massacre, also on the map, when more than 100 unarmed Australians were murdered by the Japanese. Captured Australians went to Changi Prison in Singapore and then, many of them, to the Burma Railway. Not Hec. Hec’s family did not know what had happened to him after Muar, except that he had died on or about 30-31 May 1943. That date may surprise: 1943? But Muar was in January 1942 and Singapore fell in February. That date can’t be right. But it was, as we’ll see.

After Muar, there was the Parit Sulong massacre, also on the map, when more than 100 unarmed Australians were murdered by the Japanese. Captured Australians went to Changi Prison in Singapore and then, many of them, to the Burma Railway. Not Hec. Hec’s family did not know what had happened to him after Muar, except that he had died on or about 30-31 May 1943. That date may surprise: 1943? But Muar was in January 1942 and Singapore fell in February. That date can’t be right. But it was, as we’ll see.

In the years after World War II, Commonwealth War Graves folks did token searches for men who had gone missing. In Hec’s family’s case that produced a postcard 25 years on, saying no remains found, nothing known, NFA. The postcard went to TG in Beeac as next-of-kin, in 1968. TG had died in 1953.

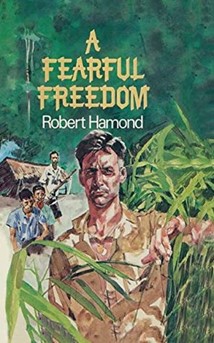

Then, 25 years after that postcard, the answer to that family question, ‘What happened to Hec?’, came in a book, published in 1984, about a British soldier called Jim Wright, who was caught behind Japanese lines after Muar in 1942, then spent three years in the jungle being hidden by local people, before being picked up in 1945 by a British submarine off the east coast of Malaya.

A Fearful Freedom was the name of the book, by Robert Hamond. That’s where Hec comes in. My aunt Madge (wife of Hec’s older brother Tom) picked up Hamond’s book in a public library in Perth in 1994 and found some interesting pages in it.

was the name of the book, by Robert Hamond. That’s where Hec comes in. My aunt Madge (wife of Hec’s older brother Tom) picked up Hamond’s book in a public library in Perth in 1994 and found some interesting pages in it.

What happened to Hec ran like this: after Muar, ten to fifteen Allied soldiers, trapped behind the lines, wandered around in the jungle, mostly unarmed, and regarded suspiciously by the local Malays, who had thoughts of turning them over to the Japanese. Along the way, some of the group died of disease, some killed themselves, some just disappeared into the jungle. Eventually, they were helped by Chinese Communist guerrillas:

Hector Stephens was now the most seriously ill; … he had displayed great fortitude through a succession of illnesses … Now [he] was unable to walk as he was stricken by wet beri-beri as a result of vitamin deficiency … “Four men carry Hector and pots and pans” [said the guerrillas; they cooked along the way]. Hector, who was most in need of medical treatment and was so nearly within reach of it, never made it but died while he was being carried to Tengkil [where there was a small hospital] on a stretcher, and was buried by the wayside.

So, Hec died, 16 months after Muar, beside a jungle track. I went to Johor in 2009 and worked out where he was probably buried (somewhere quite close to the location in the picture). The jungle has gone; the area is now covered with oil palms, a cash crop. It’s still a war grave, as far as our family is concerned. (A history of the 2/29th says Hec died on ‘guerilla operations’, which is rather stretching the story of those 16 months.)

In 2010, we collected some money from family members and donated it to the Chinese school at Kota Tinggi, the nearest big town to Hec’s grave. It is likely that the school’s pupils include descendants of the guerrillas who helped Hec. To our family, that felt like what some people call ‘closure’.

Flying Officer Hugh John Munro (Cam) Campbell, RAAF, 1916-1943

Back to the other side of the family: Uncle Cam, my mother’s younger brother. There they are below in about 1927, with Cam in the middle at the back, and my mum, Bessie, on his right. Note the bare feet: no more servants, no more big house at Portland, Papa Campbell dead, all the money gone, Cam and his sisters, Joan, Bessie and Wilma, and brother Syd living with their parents, Ina and Hugh – my grandparents – on a small dairy farm, ‘Calary’, at Tongala, Victoria.

Back to the other side of the family: Uncle Cam, my mother’s younger brother. There they are below in about 1927, with Cam in the middle at the back, and my mum, Bessie, on his right. Note the bare feet: no more servants, no more big house at Portland, Papa Campbell dead, all the money gone, Cam and his sisters, Joan, Bessie and Wilma, and brother Syd living with their parents, Ina and Hugh – my grandparents – on a small dairy farm, ‘Calary’, at Tongala, Victoria.

Cam worked on the farm – or ‘ran the farm at the age of 12’, according to my mother many years later. (His father Hugh only gradually overcame his illness.) He went to school at Echuca and played Aussie Rules (quite well). When the war came, he joined the RAAF but was only an average flyer, despite training in Australia and Rhodesia. Eventually, he was seconded to 31 squadron, RAF, flying transport planes (DC-3s) back and forth across Northern India, into Burma (now Myanmar), and ‘over the Hump’ to Kunming (now Yunnan-fu) and Chungking (now Chongqing), China. (The Hump is a range of the Himalayas.) He was Mentioned in Dispatches for one of his flying exploits.

Cam worked on the farm – or ‘ran the farm at the age of 12’, according to my mother many years later. (His father Hugh only gradually overcame his illness.) He went to school at Echuca and played Aussie Rules (quite well). When the war came, he joined the RAAF but was only an average flyer, despite training in Australia and Rhodesia. Eventually, he was seconded to 31 squadron, RAF, flying transport planes (DC-3s) back and forth across Northern India, into Burma (now Myanmar), and ‘over the Hump’ to Kunming (now Yunnan-fu) and Chungking (now Chongqing), China. (The Hump is a range of the Himalayas.) He was Mentioned in Dispatches for one of his flying exploits.

On 27 January 1943, a DC-3 took off from Dinjan, Assam State, India, to Fort Hertz, Burma. Cam was in command and there were five others on the plane, another Australian, Warrant Officer Ken Phelps, aged 22, from Wolseley, SA, three British (one aged just 21) and a Canadian. Then … nothing. The plane was reported lost.

Fellow flyers (and an Assam tea planter, with whom Cam had stayed while on leave) got in touch with Cam’s family about various scenarios. Letters came and went from Tongala to the RAAF in Melbourne and the RAF in London. By the 1960s, my mother had taken up the cause, trying to find the answer. Gradually, people died, and people forgot.

Then there was this:

That is a piece of Cam’s plane, MA 929, on a snowy hillside in Northern India. The photograph was taken on Christmas Day, 2017.

That is a piece of Cam’s plane, MA 929, on a snowy hillside in Northern India. The photograph was taken on Christmas Day, 2017.

What had happened? An American, Clayton Kuhles of Phoenix, Arizona, had made it his hobby or profession since 2003 to find crashed planes from World War II. By the magic of the Internet, a colleague of Clayton’s tracked me down, using posts of mine on RAF history chatrooms from as far back as 2010. In May 2020, I got an email saying, ‘Your uncle’s crashed plane has been found’. My immediate reaction was ‘scam!’, but it wasn’t.

First, the map provides some context: the red area was controlled by the Japanese in 1942-43. North of there, you can see Dinjan, Fort Hertz, and the Hump, where the enemy was not the Japanese but weather and wilderness. Chungking is off the map to the north-east.

This below is what Clayton Kuhles and his team found, in the 30 minutes they were able to spend at the crash site on that Christmas Day, six years ago, before the intense cold drove them away. (There are many more pictures on Clayton’s website. The Google Maps coordinates for the crash site are 28°12’2.4″N 95°58’31.5″E.)

MA 929 was upside down, with no signs of fire, no bullet holes, no human remains. The most likely explanation for the crash, Clayton believes, was a combination of bad weather and wind shear as the plane bounced back and forth between mountains. It is possible that some on board walked away, but they would not have survived long in the cold.

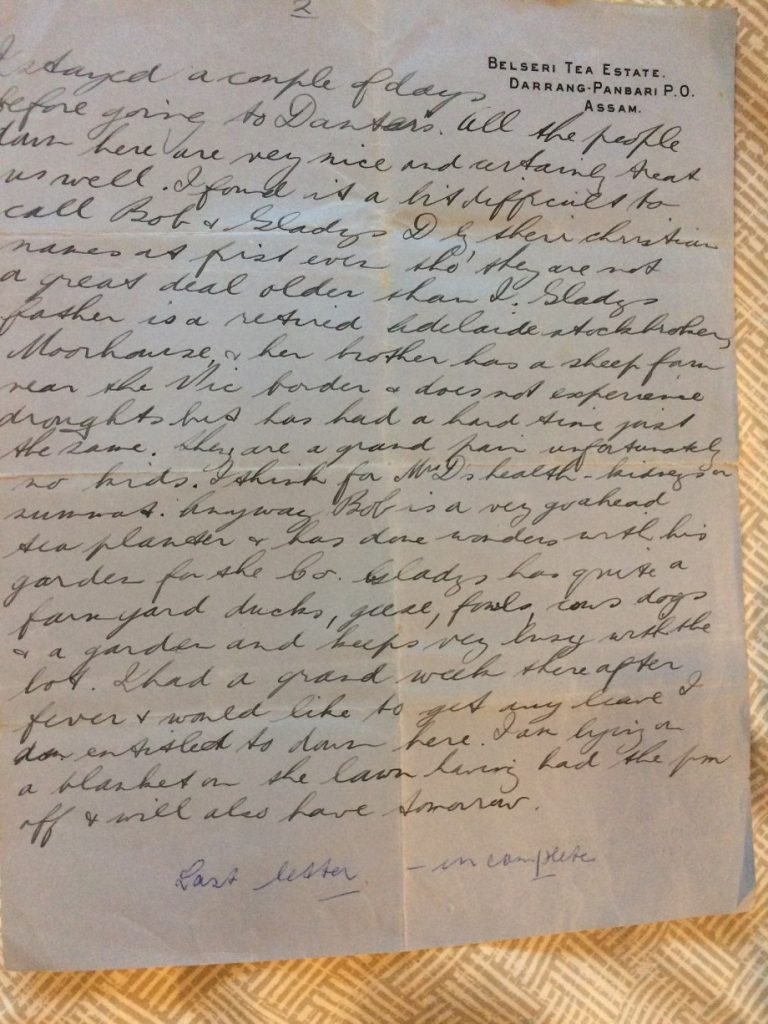

Above is a photo of MA 929’s controls, preserved by the snow and the cold, and a portrait of the other Australian, Ken Phelps. We still have dozens of Cam’s letters, including this last one, unfinished, with my mother’s 1985 note at the bottom. The letter is difficult to read but here is the final sentence: ‘I am lying on a blanket on the lawn having had the pm off & will also have tomorrow’. The day after that tomorrow, they took off from Dinjan to Fort Hertz …

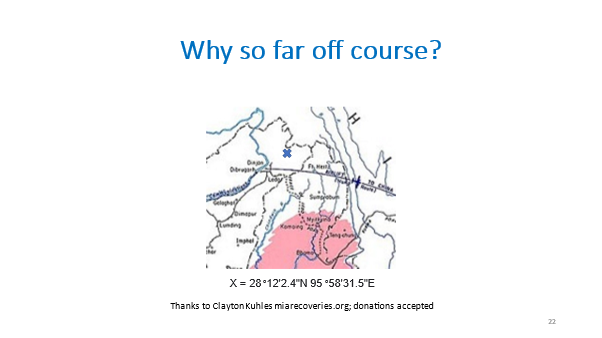

But this map below shows us something odd. Again, you can see Dinjan, Fort Hertz, and Kunming, with Chungking off the map to the north-east. You can also see that the crash site (marked X) is nowhere near the direct route from Dinjan to Fort Hertz, the plane’s supposed track; it’s about 80 kilometres to the north.

But this map below shows us something odd. Again, you can see Dinjan, Fort Hertz, and Kunming, with Chungking off the map to the north-east. You can also see that the crash site (marked X) is nowhere near the direct route from Dinjan to Fort Hertz, the plane’s supposed track; it’s about 80 kilometres to the north.

So why is the crash site there? There are some theories: Cam was avoiding bad weather on the Dinjan-Fort Hertz route; he was avoiding the highest mountains. (Neither of those possibilities stack up, according to Clayton Kuhles decades later.) The family legend, based on – perhaps embellishing – what Cam’s fellow flyers said later, ran like this: ‘Cam didn’t want to fly because the weather was bad, but a bigwig had to make the trip’. Perhaps they were going to China to pick up someone important; they did a bit of that. (Kunming was the next stop after Fort Hertz.)

Or perhaps they had to take someone to China. The only biggish wig of the six who died was Flight Lieutenant Norman Baugh MC (pronounced Bore). Baugh had got his MC (Military Cross) for escaping from Japanese-occupied Hong Kong the previous year, along with a Captain Monro. (Monro also got an MC for the escape.) Late in 1942, Monro had been flown back from Calcutta, India, to the Chinese capital, Chungking, to do ‘intelligence activities’ (spying) based in the British Legation there. Perhaps there was the same plan with Baugh; where Cam’s plane crashed is pretty much on the direct route to Chungking.

The flight plan in 31 Squadron records (Dinjan-Fort Hertz) throws no light, but if Baugh’s mission was sensitive, perhaps it was kept out of the records. (Monro’s daughter Mary wrote a book many years later; I read it but it left me none the wiser about Baugh.)

We’ll never know the full story. Anyway, we were able to pass on the news of the discovery to Cam’s sister-in-law, my aunt Joan, then aged 96, widow of barefoot Syd in that photo (and still with us today at 99). And to Ken Phelps’ family in South Australia. (Ken’s surviving brother, Ray, died early this year.) Again, ‘closure’.

Sid Ferrier again

Back to Sid Ferrier, Cam’s uncle, my great-uncle. We left him being buried at sea.

There are a couple of significant points about that photo. First, on the right with head bowed is Sid’s platoon commander, Lieutenant Hugo Throssell, who had been with Sid not long before Sid died. Secondly, there’s the date of the photo, December 1915 in the London Telegraph, three months after Sid died. By that time Throssell had received the Victoria Cross for Hill 60 and there was a campaign by him and others to get gallantry awards for the others involved in the events there.

A couple of Throssell’s platoon received the Distinguished Conduct Medal, which was the second-ranked award after the VC. Sid, however, missed out. His family never quite understood why, given the reports of his brave conduct that came back to them from Throssell and others. (In 1933, Lieutenant Hugo Throssell VC shot himself with his service revolver, leaving behind his wife, the novelist Katharine Susannah Prichard, and son Ric.)

But then this happened. That is my second cousin, Stuart Ferrier of Portland, Victoria, in April 2021, accepting a posthumous Medal for Gallantry for Sid from the Governor of Victoria, Linda Dessau. So, at last, it was Sutton Henry (Sid) Ferrier of the 10th Light Horse, MG – 106 years on.

But then this happened. That is my second cousin, Stuart Ferrier of Portland, Victoria, in April 2021, accepting a posthumous Medal for Gallantry for Sid from the Governor of Victoria, Linda Dessau. So, at last, it was Sutton Henry (Sid) Ferrier of the 10th Light Horse, MG – 106 years on.

The Medal for Gallantry is now the second-ranked medal after the Victoria Cross, having replaced the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Sid’s was for his exploits at Hill 60 alongside Throssell and the others. It came after the rules about posthumous medals were changed and followed ten years of intense work and research by the 10th Light Horse Association – a lot of it; I’ve read some of it. The research was accepted by the Governor-General’s committee on awards. What the research showed conclusively was that the paperwork at the time had been mucked up.

The Medal for Gallantry is now the second-ranked medal after the Victoria Cross, having replaced the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Sid’s was for his exploits at Hill 60 alongside Throssell and the others. It came after the rules about posthumous medals were changed and followed ten years of intense work and research by the 10th Light Horse Association – a lot of it; I’ve read some of it. The research was accepted by the Governor-General’s committee on awards. What the research showed conclusively was that the paperwork at the time had been mucked up.

My grandmother Ina, Sid’s younger sister, always reckoned Sid had missed out – she used to say to me that ‘only the officers got VCs’. Ina died in 1982 but would have been well-pleased by Sid’s MG. But I don’t believe she ever saw this one blurry photo of Sid in his Light Horse hat.

What was it all for, then?

There’s a bigger question than whether people deserved medals. The picture is of the Dead Man’s Penny or the King’s Penny, which Buckingham Palace – King George V – sent out to the bereaved families of the Great War. To try to answer those questions: What was it all for? Was it worth it? The King’s answer is clear from the Penny: ‘He died for Freedom and Honour’. In case the families had doubts, perhaps.

After the second big war, another King sent out certificates, carrying similar sentiments. We have two of them in our family; Hec’s is in a frame, Cam’s is still in the cardboard tube it came to Tongala in, back in 1946.

The Penny in the picture went to Syd Campbell’s family in Portland. Syd would not have agreed with the King about why people died in that war. We found out just a few years ago that Syd was a founding member of a Christian peace group, the Free Religious Fellowship, set up in 1911. He left the Fellowship two hundred pounds in his will.

Then there were these words in Syd’s last letter (dated 2 July 1915) to his sister, Hettie. By the time Hettie read the letter, or soon after, she would have known Syd was dead.

Then there were these words in Syd’s last letter (dated 2 July 1915) to his sister, Hettie. By the time Hettie read the letter, or soon after, she would have known Syd was dead.

We have seen enough and lost enough to realise what a horrible, disgraceful thing war is. Sometimes when one sees some fine young chap with a ghastly wound one wonders whether any quarrel between any nations is worth bothering over to the extent of killing even one human being … What awful foolishness it seems, and the individual only counts as an instrument to direct and pull the trigger of a rifle or some other machine.

*David Hector Stephens is editor of the Honest History website, convener of Heritage Guardians, and co-editor with Alison Broinowski of The Honest History Book (2017). The post was originally a presentation to U3A Banyule, Melbourne, June 2022.

Acknowledgements and sources

Some important resources are linked in the text above. As well, there are two wonderful books by the late John Hamilton, Goodbye Cobber, God Bless You (2004), which has a lot on Syd Campbell, and The Price of Valour (2012), which is the story of Hugo Throssell and frequently mentions his comrade and friend, Sid Ferrier.

Then there are the books by Ross McMullin, Farewell, Dear People (2012), and Peter Stanley, Lost Boys of Anzac (2014), which are models of how to write effectively and affectingly about war dead and their families without lapsing into schmaltz.

Clayton Kuhles does sterling work recovering planes in inhospitable territory. He accepts donations to help the work continue. His colleague, Matt Poole, worked hard to track down Campbell relatives.

Some years ago, I put together a website on my uncle, Hec Stephens, which can now be found on the National Library’s PANDORA archive.

My late father, John F. Stephens, compiled a booklet for the family on his brother Hec and his war story. My mother, Bess Stephens (nee Campbell) preserved and puzzled over the letters from and records of her brother Cam.

My second cousin, Stuart Ferrier, has helped authors find out about our mutual relatives and it was fitting that it was he who accepted Sid Ferrier’s posthumous medal from the Governor. Stuart provided the photographs of the medal ceremony.

The 10th Light Horse Association in Perth, especially Ian Gill, persisted with the task of ensuring Sid Ferrier was properly recognised and the association commissioned Major Phil Rutherford to do the research which made the case for the posthumous award.

My cousin, Don Baker, has done his own forensic research on Cam Campbell and other relatives. Don’s nephew, Mat Baker, is ex-RAAF and has shown much interest in Cam’s story.

Lynette Silver is the expert on the Parit Sulong Massacre following Muar.

Finally, the National Archives of Australia and the Australian War Memorial have preserved and disseminated the records of my two uncles and two great-uncles.

DS: Appreciate the sharing, the thought, the research and persistence that has gone into this posting. Carries so much more weight and impact than many another tribute/commemoration I’ve seen for the 25th April. What family memories and artifacts to possess … despite being colored by the far too early losses of such a number of family members. Leaves one wondering what these several young men would have done with their lives IF they had not been so pre-emptively shortened.