‘John Curtin’s War leaves questions unanswered, despite John Edwards’ best efforts’, Honest History, 12 February 2019

David Stephens reviews John Curtin’s War (Volumes I and II) by John Edwards

John Curtin has over the years become the Mount Everest of Australian political biography. Like the mountain, the key period of Curtin’s life, the war years, can be tackled from two directions, the highly personal side or the government side. Like the mountain also, Curtin has often been concealed by cloud, particularly at the higher reaches, a clear path becoming obscured just as the summit came into view.

Years ago, Curtin’s friend, Lloyd Ross, took too long to complete his biography of Curtin – and lost his way. David Day let himself be side-tracked by speculation about Curtin’s love life, but still produced a layered account. Perhaps the most useful book on the wartime Curtin was Backroom Briefings, edited by Clem Lloyd and Richard Hall, which featured the notes made by journalist Fred Smith of Curtin’s regular briefings of members of the Canberra press gallery. There have also been biographies of General Sir Thomas Blamey, JB Chifley, HV Evatt, RG Menzies, public servant Sir Frederick Shedden, and others that refer extensively to Curtin, as do the volumes of the Official History of the war. Edwards himself wrote Curtin’s Gift: Reinterpreting Australia’s Greatest Prime Minister (2005).

Years ago, Curtin’s friend, Lloyd Ross, took too long to complete his biography of Curtin – and lost his way. David Day let himself be side-tracked by speculation about Curtin’s love life, but still produced a layered account. Perhaps the most useful book on the wartime Curtin was Backroom Briefings, edited by Clem Lloyd and Richard Hall, which featured the notes made by journalist Fred Smith of Curtin’s regular briefings of members of the Canberra press gallery. There have also been biographies of General Sir Thomas Blamey, JB Chifley, HV Evatt, RG Menzies, public servant Sir Frederick Shedden, and others that refer extensively to Curtin, as do the volumes of the Official History of the war. Edwards himself wrote Curtin’s Gift: Reinterpreting Australia’s Greatest Prime Minister (2005).

As the sub-title of Edwards’ earlier book indicates, most of us kind of know that Curtin is the stand-out among Australian prime ministers, but we still have trouble understanding why this is so. Is it just that Curtin, as the man in the job during the most dangerous years of our life as a nation, has perforce to be ranked as our Prime Minister No. 1, or was there something in the way he did that job – the job which killed him – that truly merits that accolade? After all, Menzies had a couple of years as wartime PM – and made rather a hash of it compared with Curtin – though Menzies probably comes in as a place-getter in the PM Stakes if you take account of his second, longer term.

John Edwards’ two volumes, together nearly 900 pages plus notes and bibliography, are a worthy assault on the Curtin peak, but one which doesn’t quite come off. We are left teetering somewhere on the Hillary Step, within sight of the summit, with questions unanswered. Still, Edwards’ Volume I, billed – though not sub-titled – as ‘The coming of war in the Pacific and reinventing Australia’ – won the history category in the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards for 2018 and Volume II (‘Triumph and decline’) may well do the same in 2019.

Volume I takes us from Curtin’s birth in Creswick, Victoria, in 1885 through to early 1942, then Volume II carries on to his death in July 1945. There is a lot that can be said about the work, and some of it has been said in three notable reviews of Volume I by James Walter in Australian Book Review, Andrew Clark in the Australian Financial Review, and Ross Fitzgerald in other Fairfax titles, and a review of Volume II by Fitzgerald in Fairfax again. (There are presumably reviews to come in academic journals behind pay-walls but ordinary mortals will miss those.) The following remarks are by no means comprehensive. Read both volumes and decide for yourself.

Volume I takes 240 pages to get to the point where Curtin comes to power (October 1941), without really plumbing why he had become Labor Leader, and thus Prime Minister six years later. Perhaps what won him the Caucus vote in 1935 was the lack of plausible alternatives; the 1935 Caucus had just 21 members and neither of Curtin’s opponents, Frank Forde and Norman Makin, were men to set the world alight, then or later. Curtin himself had to be persuaded to stand. Jim Scullin was still around as an object lesson in what could befall Labor Prime Ministers: if presiding in war or economic crisis didn’t snooker them, their loyal colleagues did. You can see why Curtin was reluctant.

Curtin as Leader made important contributions to debates about finance, as the country gradually recovered from the Great Depression, and defence, particularly air defence, as war threatened. He had been gaoled during World War I for his opposition to conscription yet apocryphal stories were put about – perhaps to boost Curtin’s defence credentials – that he had tried twice to enlist in that earlier war. At home, Curtin saw the return to Caucus of former Lang Labor members in New South Wales, but still led an unruly Labor ‘team’. He spent lonely weeks in Canberra, far away from home in Fremantle, but seems to have stayed away from the alcohol that had handicapped him previously – or, at least, he kept his weakness private.

Volume I goes into great detail about events leading to the outbreak of war in 1939 and then to the Fall of Singapore little more than two years later. After the 1940 election, the Australian Parliament was on a knife edge, with Menzies floundering as Prime Minister and spending as long as he could in London. This part of the book makes good use of letters between Menzies and the Australian High Commissioner in London, SM Bruce. In Australia, Keith Murdoch stirred the pot as Director-General of Information with the ear of Menzies. Curtin refused to join a national government, wrestled with Labor’s resistance to conscription, battled illness, and denied he was about to give up the leadership. Evatt lurked and plotted. Curtin wrote occasionally to wife Elsie at home, disclosing his fears and insights.

At last, on 7 October 1941, Curtin assumed the prime ministership as the Independents, Coles and Wilson, ended their support of AW Fadden’s short-lived government. Labor was in a minority, the Japanese were about to attack Pearl Harbor and, soon after, take the ‘impregnable’ fortress of Singapore. Not an auspicious time for Curtin to become Prime Minister.

At last, on 7 October 1941, Curtin assumed the prime ministership as the Independents, Coles and Wilson, ended their support of AW Fadden’s short-lived government. Labor was in a minority, the Japanese were about to attack Pearl Harbor and, soon after, take the ‘impregnable’ fortress of Singapore. Not an auspicious time for Curtin to become Prime Minister.

Volume II starts as Singapore falls. Edwards gives us layers of detail on Singapore and surrounding events and Curtin hardly appears at all in the first six chapters of Volume II, other than when planning with Blamey and the newly-arrived American General Douglas Macarthur. We get the Coral Sea, Midway, Kokoda and Guadalcanal and we are up to August-September 1942.

This period is where it becomes clear that the books’ title John Curtin’s War definitely does not mean that the Australian PM ran the show. Curtin is certainly a performer in an intricate political and bureaucratic dance – also involving Blamey, Chiang Kai-shek, Churchill, Macarthur, Roosevelt, Shedden, and various supporting cast – but his moves are often laboured and always restricted. He defers to Macarthur. Prime ministerial soloes are few. Curtin’s tendency to worry and fret would have been accentuated daily as he tried to overcome, neutralise or gain the support of the other dancers.

Other sources tell us that Chifley provided great support to Curtin, though he is a relatively minor player in the Edwards version. Curtin’s Gift, which this reviewer has not read, apparently deals more with Curtin on the domestic front and thus presumably gives more space to Chifley. James Walter in his review of Volume I refers to Edwards’

underestimation of one of Curtin’s conspicuous skills: his capacity to exercise distributed leadership at home, to give difficult colleagues hard jobs (Eddie Ward, Labour and National Service, for instance), which limited their time and capacity for general criticism while drawing his closest allies – officials as well as politicians (Ben Chifley especially) – ever closer as participants in key decisions.

Lacking much of this sort of material, Edwards’ work is curiously bloodless, the players flat. Mining the archives, as Edwards does, is valuable but has its limitations in depicting human beings. We are left wondering how a person of Curtin’s admitted frailties survived and achieved in that atmosphere and with those other protagonists. Launching Volume I, Paul Keating referred to Curtin’s ‘moral authority’. But that did not extend to hands-on administration. When I interviewed Arthur Calwell in 1972 he said that Curtin had ‘relied almost completely on Shedden’.[1] Calwell was a maverick and a nuisance during the war and his evidence should be treated with caution, though Edwards comes out at pretty much the same place as Calwell on Curtin-Shedden. Edwards frequently cites David Horner’s 2002 biography of Shedden and Shedden’s own massive but unpublishable memoirs. Readers wishing to go further into war administration should venture into these sources. Shedden was a difficult individual but an important player. Horner quotes Paul Hasluck as war historian (and former wartime public servant) that Shedden was ‘one of the few outstanding men in the civil side of the Australian war effort [but] … his achievement was often hidden’.

So, John Curtin’s war 1942 to 1945, as presented by Edwards, is a story with many protagonists. The narrative is outwardly focussed, on the threat and dealing with it, partly because that was the author’s intention and partly because that is where the evidence takes him. As noted above, he makes good use of archival material, private papers, and previously published (but underused by other writers) government documents. The result is more military or administrative history than biography, or even ‘life and times’, and readers who are not military history buffs will nod off during or skim over some chapters.

Japanese newspaper, Singapore (JavaGoldBlog)

Japanese newspaper, Singapore (JavaGoldBlog)

When Curtin is allowed to take centre stage, however, the book lifts. ‘Without resorting to hagiography or polemics’, said James Walter in his review, ‘Edwards persuades us not only of the courage and tenacity with which Curtin fought his corner, but also displays a sure sense of the complexities, anxieties, failures, and nuances of the deliberative processes and relationship building this entailed’.

Edwards pauses often enough in his narrative to give us an inkling of Curtin’s state of mind at crucial junctures. In early 1942, he is just as much in the dark about the plans of the Allies as about the next moves of the Japanese. Later that year he is looking for signs that the tide of war is turning. (Some readers may be surprised that the tide turned as early as it did – after Midway and Kokoda – but there was still a long way to go to the sudden victory in August 1945.) By mid-1943, he has settled a way of reconciling his personal shyness with the need for consultation with the people who mattered, from Macarthur and Blamey down; the words ‘networking’ and ‘focus’ were almost certainly not in vogue in 1943 but Curtin had to be good at the first and he displayed the second in spades.

In 1944, the last full year of the war and of Curtin’s term and life, he is a reluctant traveller to London and Washington. (He hated flying and wasted an awful lot of time with his occasional train trips home to Fremantle.) Here, Edwards is good on the atmospherics of the meetings held. Curtin had made things difficult in 1942 for Churchill – who remembered – and he would have picked up the vibe that Roosevelt had a dim view of Australians as soldiers, of Evatt as an emissary, and of Australian pretensions generally. Edwards refers to ‘Roosevelt’s faint disrespect for Australia and for its leader’ and describes the Curtin-Roosevelt meeting in April 1944 – the only one they had and it lasted just an hour – that was not a raging success. (Edwards uses Roosevelt’s military assistant’s notes of the meeting.) By this time, too, both Roosevelt and Curtin were ill. Roosevelt died in April 1945, Curtin in July, after a long decline over the previous nine months. War casualties, both of them.

So much for fighting the war. What about afterwards? While Edwards in Curtin’s Gift, and other writers like Stuart Macintyre in Australia’s Boldest Experiment: War and Reconstruction in the 1940s, go more deeply into the plans of Curtin, Chifley, HC Coombs and others for Australia domestically after the war, Edwards leaves no doubt in his Volume II that Curtin, unlike Roosevelt, did not see the war as bringing in wholesale changes in world power alignments. The British Empire-Commonwealth was the key to Curtin’s post-war vision. The Dominions were to have a higher profile (compared with Britain) than before the war, but it was still to be ‘the Fourth Empire’ and still one where the white man prevailed. Edwards includes an illuminating vignette of Sir Owen Dixon, judge and Australia’s man in Washington, being shocked when he realised Roosevelt was comfortable with post-war ‘intermixture of the races’. ‘For Dixon, as for Curtin’, Edwards concludes, ‘the war in the Pacific was a war for the white man’. Curtin raised with Roosevelt ‘the future of the white man in the Pacific’ but Roosevelt was unimpressed.

Now for the books as a (weighty) package. Edwards (and Curtin) deserved better of the publisher, Penguin Random House, and editors. The first print of the first volume left the author’s name off the front of the dustjacket – Crikey has a picture as proof. Among many examples, Volume I has inconsistent capitalisation in the Table of Contents, Volume II has a typo on page 1 (‘the mid-March’), there are inconsistencies in the punctuation of dates and quotations (see, for example, page 26 of Volume II), and in place names (‘South West Pacific’ and ‘South-west Pacific’ on pages 162 and 163 of Volume II). Occasionally, dramatis personae are reintroduced when they have barely left the stage. In the photograph section of Volume I, Prime Minister Menzies and Governor-General Lord Gowrie disappear down the page gutter in badly placed double page spreads. The bibliographies of both volumes refer to a ‘Wilmot Chester’ as author of a book called The Struggle for Europe. You would think that between Volumes I and II someone might have picked that one up and transposed the Wilmot and Chester.

Curtin with Eleanor Roosevelt, September 1943 (John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library)

Curtin with Eleanor Roosevelt, September 1943 (John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library)

More important than these relatively trivial (but irritating) lapses, however, are the frequent occasions where Edwards seems overwhelmed by the many elements of the complex story he is telling. He often strings together a bunch of clauses before throwing in a subject almost as an afterthought at the end of an overlong sentence. Thus, on page 99 of Volume II:

The accumulation of stress, his solitary life in Canberra at the Lodge while Elsie remained in Cottesloe, the bitter Canberra winter, coal strikes, rejection of his requests to Churchill and Roosevelt, the fighting withdrawal of the Australians from Kokoda back towards Port Moresby, the uncertainty of fighting in Guadalcanal, all contributed to a prolonged gloomy spell for Curtin despite the American naval victories.

The reasons for Curtin’s gloom would have been presented more strongly had the final dozen or so words in that lumbering sentence appeared ahead of all those clauses, and as a sentence on their own. Books about World War II need not, even for the sake of atmosphere, rattle and clunk along like an RAAF DC-3 badly in need of a service.

Edwards and his editors also struggle with syntax, the construction of sentences so that nouns, verbs and other parts of speech relate properly to each other. While there are examples in both Volumes, here is one from Volume II (page 356):

Initiated in 1941 and continued under wartime powers, Curtin and Chifley also planned to give a new and permanent legislative framework to the central banking role of the Commonwealth Bank.

Read it twice and you can work it out, but you shouldn’t have to read it twice. Curtin the journalist would have been embarrassed by that sentence. The author and publisher should be, too. Some sentences are just silly, like this one on page 144 of Volume I: ‘Troubled by a bad heart, the 59-year-old Lyons died on Good Friday, 7 April 1939’. More than troubled, one would have thought.

Reviewers should not gloss over such clangers – clangers which some Australian publishers still manage to avoid. (James Walter mentioned the ‘accessible prose’ of Volume I and Ross Fitzgerald described Volume II as ‘finely written’.) All that said, this reviewer thought the two Edwards volumes were well worth the (sometimes difficult) read for what they say about Curtin and Australia in some crucial years, even if they do not fully answer that vital question, ‘how on earth did he do it?’ But if you want 900 pages of ‘life and times’ as literature and as a real insight into character (albeit with some gossipy padding), get hold of Roy Jenkins on Churchill. (He mentions Curtin – once.) And, to be fair to Edwards, read Curtin’s Gift, too.

* David Stephens has been the secretary of the Honest History coalition and is editor of the Honest History website (honesthistory.net.au). He was co-editor with Alison Broinowski of The Honest History Book (NewSouth 2017). His MA thesis (Monash University 1974) dealt with the Curtin and Chifley governments, 1941-49.

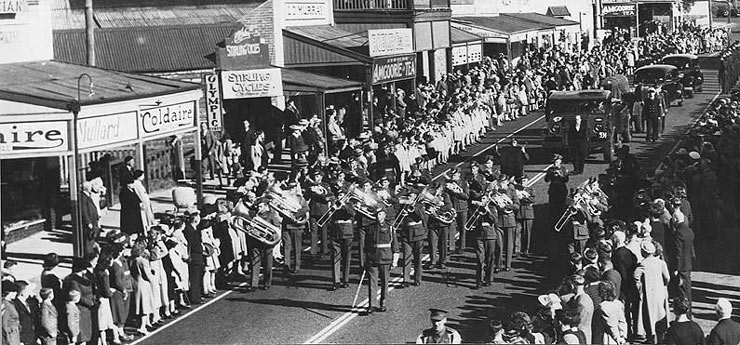

Curtin funeral procession, Cottesloe WA, July 1945 (John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library). There is a video (1945 newsreel) of Curtin as Prime Minister, including extensive coverage of his funeral.

Curtin funeral procession, Cottesloe WA, July 1945 (John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library). There is a video (1945 newsreel) of Curtin as Prime Minister, including extensive coverage of his funeral.

Endnote

[1] The full reference is as follows:

Nobody relied more on leading public servants than Curtin. Curtin relied almost completely on Shedden, who was the Secretary of Defence. Curtin had a remarkable capacity for drawing people to him and he saw the wisdom of Menzies’ act in bringing in Essington Lewis and giving him tremendous authority and saying, “Well, you start up the war effort and get everything done that you possibly can”. After Pearl Harbour Curtin made Essington Lewis a Czar. (Interview with Mr A.A. Calwell, Canberra, August 18, 1972, David Stephens, Papers, 1972, National Library of Australia MS 4625)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.