David Stephens[*]

‘Dunera Lives is a tribute to resilience and a testament of worthy contributions to Australia’, Honest History, 12 July 2018 updated

David Stephens reviews Dunera Lives: A Visual History, by Ken Inglis, Seumas Spark and Jay Winter, with Carol Bunyan. See also the speeches from Frank Bongiorno (Canberra) and Raimond Gaita (Melbourne) at the launches of the book. Another launch speech from Nick Gruen, son of Dunera boy, Fred. Review from Ebony Nilsson in ANU Historical Journal.

***

Fearful or insular societies are always wary of ‘the other’, the person who looks, acts, speaks, prays, eats, smells different. Many ‘others’ in many countries have learnt this to their cost – German-Australians in World War I, Japanese-Americans in World War II, Kurds in Turkey, Rohingya in Myanmar – particularly if there is a war on and the words ‘security threat’ can be plausibly uttered.

The Dunera boys – actually youths and men – were ‘others’, many of whom, through grit and resilience and innate talent, worked their way through that status to become valued members of post-World War II Australian society. Their widely differing stories are told – and their immense contribution described – in this book, the last (but for Volume 2) to carry the name of distinguished Australian historian Ken Inglis, who died in December 2017.

The Dunera boys – actually youths and men – were ‘others’, many of whom, through grit and resilience and innate talent, worked their way through that status to become valued members of post-World War II Australian society. Their widely differing stories are told – and their immense contribution described – in this book, the last (but for Volume 2) to carry the name of distinguished Australian historian Ken Inglis, who died in December 2017.

The volume under review is actually the first of two, and it is beautifully produced by Monash University Publishing. Volume 1 is divided into eight sections, although the bulk of it is in Section 5, describing internment in Hay, Orange and Tatura 1940-45. The sectional structure gives the impression of a dossier or official report, but this is quite appropriate given the subject matter: the book is indeed a report to all of us on some of the implications of total war, as much as it is a memento or talisman for the Dunera community, which still thrives today through reunions and the efforts of extended families. (For other Dunera material on the Honest History site, including Dunera community newsletters, use our Search engine.)

These facets of our war history – the facets that are not about blokes in uniform – need to be reported and publicised, even as ‘mainstream’ war history regresses more and more (with some notable exceptions) into ‘boys own adventure’ stuff – to the extent that there is a mass market for even the most mundane and repetitive military history published to mark the anniversary of some retrospectively over-hallowed event. (This review was written at the time of the centenary of the Battle of Hamel. We’ve almost survived the centenary of World War I, but look out for the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II.)

The first 100 pages of Dunera Lives cover Germany and Austria before the war as Nazi power grew, the movement of Jews and other refugees to Britain, their transformation into ‘enemy aliens’ as the war intensified in 1940 and they came to be perceived as threats in an atmosphere of xenophobia, and the overcrowded MS Dunera voyage to Australia from July to September 1940. There were about 2500 men and youths on the Dunera, about 80 per cent of them Jewish, though by no means all of them practising, let alone devout. In 1940, too, the Queen Mary sailed from Singapore to Australia with another 265 internees. The illustrations in these sections of the book indicate the harsh conditions and brutality the internees endured on their voyages, though those who came on the Queen Mary fared rather better.

Then there were the years in the Hay, Tatura and Orange camps, which, rather by contrast with the Dunera voyage, ‘were confined spaces rather than prisons, in the sense that the internees virtually governed themselves … There were artistic and musical circles, study groups, religious communities and sports teams, all organised by the inmates.’ The headings of the book’s sub-sections give an idea of the content: ‘Waiting for freedom’, ‘Adaptation’, ‘Learning and living’, ‘Between bitterness and hope’, ‘Dreams and reflections on living in limbo’, ‘Landscapes and longing’, ‘Filling time’, ‘Seeking God’.

After incarceration, Dunera careers diverged. Internees began to be released in 1941, many of them returning to Britain, and by early 1943, over 1800 had left the camps. ‘Enemy aliens’ were redesignated as ‘refugee aliens’. Some internees went to university. The book has photographs of Dunera boys fruitpicking in the Goulburn Valley as members of the 8th Employment Company.

Although some Dunera boys joined the Australian forces during the war and others found civilian jobs while the war continued, by 1950 only somewhere between 700 and 900 Dunera boys were still living in Australia. These men merged into post-war Australian society, composing music and taking photographs, designing furniture, teaching and researching in universities, painting, making and acting in films, practising law, and so on. Where and how they made their lives in Australia reflected their predominantly middle class, cultured backgrounds in Europe. Appropriately, a sub-section towards the end of the book is headed ‘Australian faces’; now not ‘others’ at all.

‘This is’, the authors say, ‘a story of survival after the humiliation of internment and transportation to Australia’. It is about the integration of European Jews into the Australian Jewish community, but more than that it is a story about the resilience of Jews and non-Jews. The sub-sections headed ‘Commemoration’ and ‘Legacies’ show how this resilient strand has been continued and celebrated through the efforts of the Dunera community.

Internees, including Dunera boys, Tatura camp (NMA/AWM)

Internees, including Dunera boys, Tatura camp (NMA/AWM)

Useful appendices and tables cover chronology, reasons why internees left camps, ships on which internees returned to Britain, and name changes – Dunera boys were quite willing to change their names to fit into Australian society. The dozens of names in the acknowledgements section indicates the amount of collaboration that has gone into the book’s production. Carol Bunyan’s collation of masses of material deserves special praise.

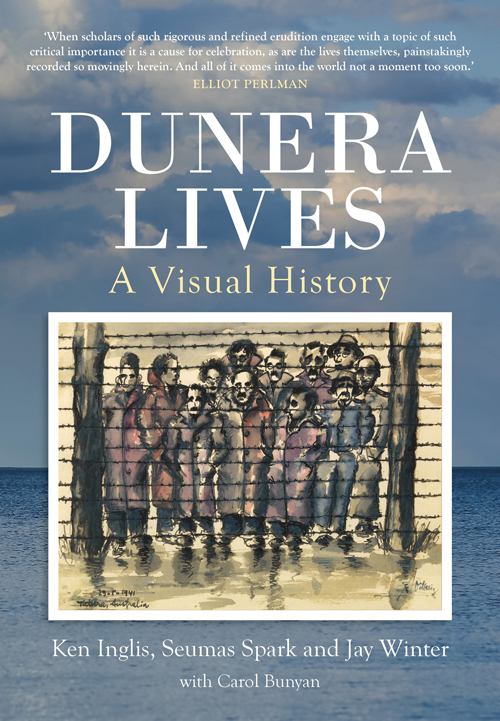

Dunera Lives lends itself either to absorbing at a long sitting or to dipping into. Dunera descendants naturally will look first for the stories of the people they know. In some cases, they will come across material that is entirely new to them. The illustrations and the text complement each other strongly – the illustrations are not just pictures, but what co-author Jay Winter described at the Canberra launch as ‘visual testimony’.

For example, there are views of life before Dunera (Gerd Bernstein, 16 years old, with his family in Berlin in 1938 – nearly 80 years later, as Bern Brent, he spoke at the Canberra launch of the book; New Year’s Eve, Singapore, 1939), life on Dunera (sleeping, overheating, exercising), and life after Dunera and in the camps (a dust storm at Hay, eucalypts at Tatura). There are paintings, notably the Tatura portraits by Erwin Fabian, Fred Lowen and Theodor Engel, and Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s Mural of the Life of Christ, done with his students at Geelong Grammar School, where he had been allowed to teach, and emphemera, like the ‘camp constitution’ prepared on the Dunera (in anticipation of incarceration, where order would be required) and ‘camp currency’ from the Hay camp.

But these are just random examples; the book has hundreds of photographs of people and places, paintings and sketches, portraits and cartoons, documents and internee-produced newspapers, all illustrative of the great variety of Dunera lives. There are also poems, such as Oswald Volkmann’s rueful ‘Taturalia’ (‘Next to the camp that’s called Tatura/Live the girls: bella figura./But you can’t do more than stare/They’re beyond the fence – out there!’). One imagines that Dunera boys found plenty of time to write. When not writing, they ran lots of concerts and dramatic productions, and the book has a number of programs and playbills, like one for a concert at the Hay camp in February 1941, where JS Bach, Schubert and Mozart were featured.

Apart from its intriguing content, the book is a tribute to Ken Inglis, a tower of strength and imagination in Australian history and the life of the mind. He had been interested in and researching the Dunera story for many years – indeed, since his undergraduate days at the University of Melbourne, where one of his teachers was Dunera boy Franz Philipp – and it is fitting that all royalties from the book are being donated to the Ken Inglis Historical Fund at Monash University.

Volume 2 will add an extra layer to the complex Dunera story. It will, we are told, be more of a narrative, and there is a mass of material still to be mined, with Spark, Winter, Bunyan (and associates) keeping a promise to Inglis to bring the second book out. This reviewer looks forward to it. The khaki-conscious commemoration mainstream mouths platitudes along the lines of ‘it’s not about war, it’s about love and friendship’. Memory and commemoration is, of course, about all of these things. But in the Dunera story, love and friendship deserves top billing.

Manus Island detainees (Echonet Daily/AAP/Eoin Blackwell)

Manus Island detainees (Echonet Daily/AAP/Eoin Blackwell)

A final point: at about the time I began to think about this review I heard federal Attorney-General Christian Porter use the phrase ‘keeping Australians safe’ perhaps a dozen times in a short interview about security legislation. That phrase is a dog whistle that gets a positive reaction from the fearful – or the Attorney would not use it. One wonders how that reaction would translate into a reception for a new Dunera, should one arrive in the Australia of 2018.

Come to think of it, we know the answer to that question. The travellers on modern Duneras are festering on Manus Island and Nauru, but, like the Dunera boys, they are also showing resilience – a characteristic that this wide brown land could always do with more of. Who loses most from this modern incarceration: the ‘others’ or us? Dunera Lives, like all good history, holds up a mirror to today.

[*] David Stephens is editor of the Honest History website, secretary of the Honest History association, and co-editor of The Honest History Book.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.