‘Anzac Centenary Local Grants: conservative commemoration’, Honest History, 30 June 2014

This note comments on the statistics set out in Honest History Factsheet No. 2 on the Anzac Centenary Local Grants Program.

Ken Inglis says in his book Sacred Places that Australia already has more than 5000 war memorials and monuments. Their ubiquity is a reflection of community grief after the two world wars. Inglis shows that the term ‘war memorial’ became popular immediately after World War I, when it came

to stand as a community’s statement of bereavement, pride and thanks-giving … All over Australia, local circumstances put their imprint on a common movement of commemoration. The theme was universally the mourning and honouring by name of the men who went to the war from this place; and on that theme people in every city, suburb, town and township improvised their own variations, negotiated their own communal understandings of the meaning of the war in appropriate monument and ceremony. The making of Great War memorials in Australia was a quest for the right way, materially and spiritually, to honour the soldiers.[i]

Kempsey, NSW. A ceremony in progress at the town’s WWI war memorial (source: Australian War Memorial H15862; the Memorial has over 19 000 items filed under ‘War memorials’ photographs)

Kempsey, NSW. A ceremony in progress at the town’s WWI war memorial (source: Australian War Memorial H15862; the Memorial has over 19 000 items filed under ‘War memorials’ photographs)Inglis describes the contest immediately after the Great War between ‘the sacred and the useful’, essentially between, on the one hand, a preference for bricks and mortar monuments and, on the other, for civic buildings with a suitably commemorative name.

Believers in traditional monuments replied [to the utilitarians] that a community was not truly engaged in an act of commemoration when it gave the name of memorial to some public resource which should have been provided anyway.[ii]

Some communities saw spirited debates between the proponents of the two views but the traditionalists won out.

People in most places voted for monumentality over use … Of every hundred Great War memorials about twenty are halls and one or two are hospitals, schools and other functional forms, eighteen are both monumental and useful, and the other sixty or so are monuments.[iii]

The first large batch of projects funded in 2014 under the Anzac Centenary Local Grants Program pretty much replicates Inglis’s estimate of the memorials built after 1918 – around 60 per cent are to do with monuments. Admittedly, today’s lot have a wider range of forms than the traditional monument – there are gardens and water features as well as statues and honour boards – but the preference for non-utilitarian commemoration is still strong. Why so? Is this what communities want?

The Minister’s words about communities echo Inglis’s summary of attitudes immediately after the Great War. Communities link commemoration to a sense of place; a spokesman for the Minister told Honest History that, in a community-based commemorative program, it was inappropriate to argue with community preferences.

It needs to be remembered, however, that the choice of commemorative projects under the Program is quite narrow: public commemorative events, new memorials and honour boards and restoration of old ones, preservation of memorabilia and artefacts, and school projects. ‘Construction and repair of buildings, including museums, memorial halls and sporting facilities’ is explicitly ineligible.

One hundred years on, the contest between traditional and useful commemorative projects is not even joined; traditionalism is enthroned. Room for manoeuvre is further curtailed by the introductory sentence to the project criteria: ‘Proposed projects and events must be directly commemorative of the involvement, service and sacrifice of Australia’s servicemen and women in the First World War.’ (Emphasis added.) Commemoration is to be explicit and robust.

Further, the committees chosen by local MPs to consider proposals seem to have been drawn from a fairly narrow spectrum of the community. While Honest History has not attempted to analyse actual committee membership, the criteria for MPs choosing committees give some strong hints: ‘an Electorate Committee consisting of representatives from community groups interested in the Anzac Centenary, e.g. ex-service organisations (ESOs), educational institutions, museums, local government etc’. Regardless of who the committees were, however, they were bound by the narrow project criteria.

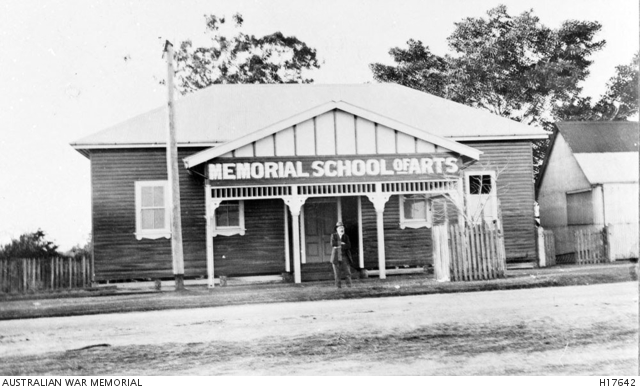

Caboolture, Queensland. A Memorial School of Arts erected as a WWI War Memorial (source: Australian War Memorial H17642)

Caboolture, Queensland. A Memorial School of Arts erected as a WWI War Memorial (source: Australian War Memorial H17642)It is not surprising that a program which starts from a particular conception of what is appropriate commemoration and sets its ground rules accordingly should produce a predictable range of projects. The community – or, at least, the part of it which is interested – is presented with a received view of commemoration, one that has essentially been unchanged for almost 100 years. It accepts the received view and goes on to propose projects which will perpetuate it.

If, on the other hand, the criteria had been wider (and perhaps the committees broader) the Anzac Centenary Local Grants Program might have generated local projects in areas like drug rehabilitation, homelessness, employment, respite care, juvenile offenders’ programs, teachers’ assistance, and aged care, as well as programs directed at veterans suffering post-traumatic stress disorder or the effects of Agent Orange. There might even have been some utilitarian buildings built. The designation of such projects as ‘Anzac Centenary’ would have added the necessary commemorative element.

The successful grant applicants under the Program are fairly evenly distributed between RSL sub-branches, ad hoc commemoration committees, schools, historical societies, museums, progress associations, and local government bodies, reflecting the wide range of bodies eligible to apply. It is the narrowness of the project criteria, rather than the bodies who are able to apply, that makes the Program so restrictive and unimaginative.

The eligible applicants include ‘[o]ther non-profit community organisations’. This could have covered groups not interested in traditional forms of commemoration but having the capacity to develop projects targeting community needs which are currently not met or only partly met by other funding.

It is possible also that non-traditional projects might more closely reflect the ideals that we attribute to the men and women who died in war. Presumably the dead of World War I had a view of the sort of Australia they wanted to see after the war – ‘the land fit for heroes’, an Australia which was better than the one they left behind. Not necessarily an Australia covered by memorial gardens, dotted with monuments and echoing to the sound of constant commemorative pageants.

A century on, it would be nice to think we have moved on from the way we thought then. The Anzac Centenary Local Grants Program was an opportunity to do commemoration differently. It has been an opportunity lost.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.