‘Anzac is not just the One Day of the Year: the myth that just keeps on giving’, Honest History, 16 June 2017

While we have been promoting The Honest History Book – which is doing very well, thank you – we have occasionally detected a public inability to distinguish between Anzac Day – 25 April – and the Anzac myth or legend, that khaki thread of our history which, we argued in the book, needs to be reduced in proportion compared with other important parts of our national story. For example, a couple of radio programs and one journalist said the opportunity to talk to us, or write about the book, had passed because ‘Anzac Day was a couple of weeks ago. Maybe we could look at all this next April.’

Kevin Rudd, Anzac Day 2008, Sydney (ABC)

Kevin Rudd, Anzac Day 2008, Sydney (ABC)

Actually, the book has relatively few mentions of Anzac Day. On the other hand, it has a lot about the Anzac myth and, more generally, about how bullshit tends to expand to fill the space available – unless you push back against it.

Of course, the Anzac myth bulks particularly large around 25 April but it is still a lurking presence for the rest of the Australian year. According to then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2010, Anzac (or ANZAC as he styled it) shapes our nation’s life, offers ‘quiet counsel and gentle direction as we seek to chart our future’. Its flame needs to be nurtured and its torch passed on. (We have often used Rudd’s overblown piece of rhetoric as a prime example of Anzackery, ‘[t]he promotion of the Anzac legend in ways that are perceived to be excessive or misguided’, according to the Australian National Dictionary.)

Those three paragraphs serve as introduction to our brisk review of a bundle of items, some dated to an Anzac Day, some not, which poke in their different ways at the Anzac flame. They may not all offer gentle direction or quiet counsel but we will present them anyway. They are all food for thought, an activity that is often set aside where Anzac is concerned: count the number of times the adjective ’emotional’ is used in a commemorative context and consider how uncomfortably emotion and thought co-exist. Emotion often drives out thought.

In April this year, on his blog Camden History Notes, Ian Willis reported a lecture by historian Jen Roberts to alumni of the University of Wollongong. The lecture was titled ‘Men, myth and memory’ and, says Willis, it ‘left none of the alumni present in any doubt about the contested nature of Anzac and that there is far from just one truth. Anzac is a fusion of cultural processes over many decades and it has been grown into something bigger than itself.’

Roberts’ lecture ranged widely over the shades of meaning of Anzac and concluded that it is for all of us ‘to make a choice about the meaning of Anzac’. In somewhat similar vein, Alison Broinowski and I said this in the final chapter of The Honest History Book:

Anzac may still be a secular religion for some Australians, but it is not the established church; other Australians have the right to be atheist or agnostic about it … Anzac atheists and agnostics should respect the adherents of the Anzac religion, but they should not in a democracy be required to worship at its altars.

Vimy Ridge commemoration, April 2017 (Ouest-France)

Vimy Ridge commemoration, April 2017 (Ouest-France)

Also on Camden History Notes from May this year is a reprint of a Canadian blog about ‘Vimyism’, a phenomenon which Ian Willis rightly compares with Anzackery, the over-the-top version of the Anzac myth. (We do a sharp number on Anzackery in The Honest History Book.) Willis’s guest blogger, Andrea Eidinger, comments on history professor Mary-Ellen Kelm’s review of The Vimy Trap: or How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Great War by Ian McKay and Jamie Swift. (Readers will know that social media tends to spawn these long attribution strings.) Vimy 1917 is roughly Canada’s equivalent of Gallipoli 1915. Kelm gets to the nub thusly – and it sounds very familiar to connoisseurs of Anzackery:

What McKay and Swift are arguing is that Vimyism – “a network of ideas and symbols that centre on how Canada’s Great War experience somehow represents the country’s supreme triumph [and]… marked the country’s birth,” has flattened the complex, contradictory and terrifying reality of the First World War into a simplistic, militaristic “big bang theory” of Canadian history.

Kelm’s note hints at conflict in the discipline of history and there was certainly that in an exchange on the World Socialist Web Site, an always useful alternative source of news and views. This stoush was between WSWS writers Sam Price and Tom Peters, in one corner, and, in the other corner, New Zealand children’s writer, Maria Gill, author of ANZAC Heroes, published by Scholastic in 2016 (and also available in Australia).

Gill’s book is about 30 New Zealanders and Australians involved in both major wars. Gill, in the book and in a response to criticism by Price and Peters, said the book was written ‘so that children can read historical accounts of what happened in the past so that we can learn from them and don’t repeat the same mistakes’. Price and Peters, unconvinced, concluded Gill’s (government-funded and award-winning) book was part of ‘the strenuous efforts being made by governments, with the help of well-paid academics and hack writers, to overcome the deeply ingrained anti-war sentiment among young people’. They came back for another whack more recently.

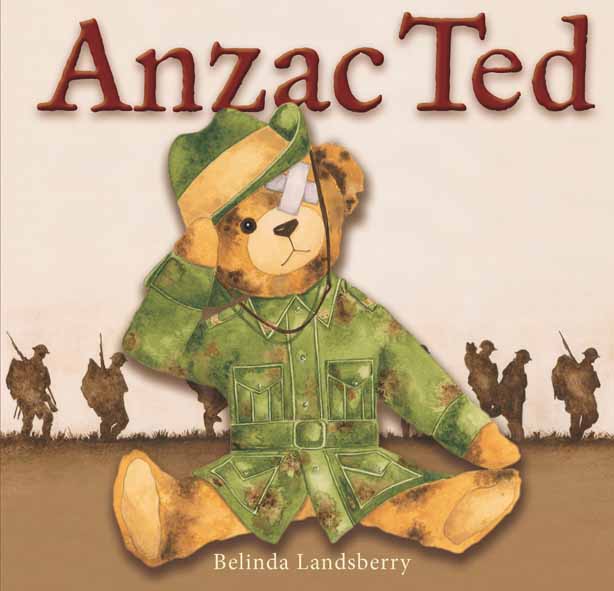

The present writer has not read ANZAC Heroes so will not pass judgement on it, though it does sound very like Audacity, published on this side of the Tasman and also government-funded and award-winning. Governments, and people who work for the government shilling, certainly put lots of effort into spruiking a particular view of war to young people. Peter Stanley noted that even the childish fondness for teddy bears is made use of in this regard.

Why does this piling on to kids matter? The present author said this in chapter 9 of The Honest History Book (‘Anzac and Anzackery: Useful future or sentimental dream?’): ‘Encouraging our children to take responsibility for the torch of remembrance only makes sense if we expect them at some time in the future to have to lay down that torch and take up weapons’. That’s why it matters.

Then there is Vietnam. Mark Dapin’s chapter in The Honest History Book is called ‘ “We too were Anzacs”: Were Vietnam veterans ever truly excluded from the Anzac tradition?’ Dapin offers strong evidence that they were not, which underlines how Anzac has been and should continue to be a talisman and tradition for serving soldiers, provided particularly that it is balanced by their professionalism and does not put pressure on them to be larger than life, as inheritors of an over-egged Anzac tradition.

Ruth Clare talks to Richard Fidler about her childhood in the shadow of a violent Vietnam veteran father. Politicians who prattle about ‘the sons of Anzacs’ – even as they cynically and carefully calibrate how many young men and women need to be sent off to foreign fields as downpayment on an increasingly ill-advised ‘alliance’ – need to listen to programs like this one. They put boilerplate patriotic war talk in perspective.

Passing the torch of remembrance, Beaudesert, Qld, Anzac Day, 2015 (Beaudesert Times)

Passing the torch of remembrance, Beaudesert, Qld, Anzac Day, 2015 (Beaudesert Times)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.