‘St Mark’s remembers Anzac Day’, Honest History, 19 September 2015

Doug Hynd reviews the April 2015 issue of St Mark’s Review

__________________________

This thematic issue ‘St Mark’s remembers’ on ‘remembering Anzac Day’ is, in the best sense of the term, a smorgasbord, in both its varied intellectual and disciplinary approaches to the issue and in the differing literary forms through which the topic is engaged. While any given reader is unlikely to find every article equally to their interest or taste, they are equally unlikely to come away from the issue without having found some items that they will reflect on and come back to.

The editor, Dr Michael Gladwin, is a church historian and the author of a recent published history of Australian Army chaplains. He has clearly drawn on his engagement in this field to gather together a diverse range of contributors.

In his editorial he describes the edition as falling into two sections. The first is ‘a series of reflections on war and Anzac Day from a theological perspective – from two Australian theologians and two senior Australian Army chaplains. The second set of articles approach the issues from a historical perspective.’ (vii)

While it is the second set of articles that are likely to attract the attention of the readers of this website, the first few pieces are, I think, worth attending to, for what they say about contemporary Christian reflection on questions of war and peace and similarly what they have to say by way of evidence on the way Anzac Day is being practised and interpreted within the Australian armed forces today. These articles can, I would judge, be read with profit by both insiders of the Christian community – as a contribution to the conversations within that community on some critical issues – and by outsiders to that community.

Among the themes that emerge from the issue Gladwin highlights

a more pervasive and influential Christian dimension to Anzac Day commemoration than some secular commentators have suggested; various ways in which popular and scholarly representations of Anzac, including those of filmmakers and historians, have sidelined or sidestepped its religious origins and character; the complex interaction of civil religion, religion and spirituality in both Anzac Day and the Anzac legend; and the extent to which Anzac Day reflects a personal and spiritual quest among Australians for national identity and a sense of the transcendent in the face of an increasingly multicultural and pluralist society. (vii)

This summary is helpful particularly in locating much of the confusion in the debates between the history of Anzac Day, its appropriation as myth at a cultural level, and individual engagement at a personal and experiential level. Gladwin closes his editorial by characterising the exercise of editing this edition of the journal as one which contributes to the exploration of the question, ‘What has Gallipoli to do with Jerusalem?’

I will say little about the theological pieces apart from commending the powerful opening piece by Andrew Cameron, Director of St Mark’s, in which he draws appropriately from the work of Karl Barth, whose own commitment to theology in a new key was provoked by how German theologians approved their nation’s engagement in World War I. I will also resist the temptation to engage critically in this context with the contributions from chaplains which deserve discussion within the Christian churches.

What I can most helpfully do is to note several of the articles which contribute something fresh to the historical and sociological interpretations of Anzac Day and its reception within Australian society. The pieces by John Moses and Frank Bongiorno provide more in the way of surveys of current debates rather than breaking new ground and are likely to be most helpful for those seeking to orient themselves to developments in scholarship and ongoing controversies.

The next few articles represent scholarly work which casts fresh light on issues from a variety of interesting and relatively unexplored angles. Daniel Reynaud explores ‘Religion and the Anzac legend on screen’, taking us into the world of popular culture. Greg Melleuish brings into focus the connection between Anzac and Protestant sectarianism and the controversy over Britishness, through the career of the Reverend C D Forscutt. Raymond Canning takes up a family perspective through an exploration of the involvement in war of his great-uncle, his interaction with chaplains, a questioning of how we might appropriately remember and what remembering involves.

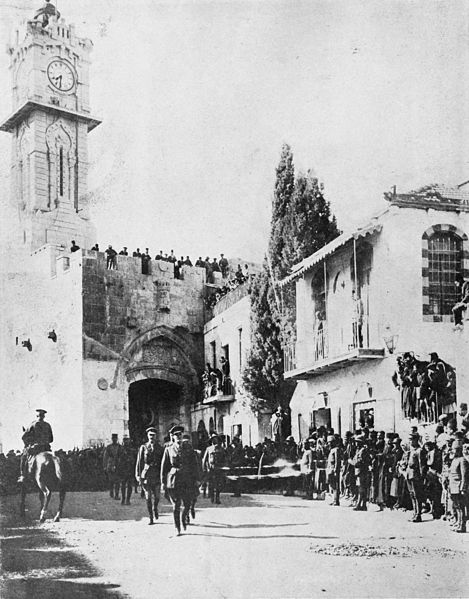

British General Sir Edmund Allenby entering Jerusalem on foot to show respect for the holy place (11 December 1917) (Wikimedia).

British General Sir Edmund Allenby entering Jerusalem on foot to show respect for the holy place (11 December 1917) (Wikimedia).

Then there is Colin Bales, who provides fresh light on the debate over the extent and character of religiosity in the Australian community in World War I through an analysis of war grave inscriptions in Belgium and France. He argues that the evidence from these inscriptions shows both a stronger connection to traditional Christianity than some other historians had found to be the case and a growing sense of Australian identity.

The closing article by Christopher Hartney, ‘Neither civil or secular: the religious dimension of Anzac’, revisits familiar territory but does so with an intellectual sophistication and verve and in a way that should revivify if not reframe the debate over the religious character of Anzac. He explores the placing of the Australian War Memorial and how it functions as sacred space and as a particular kind of sacred that is as marked by what it omits as what it includes. I hope that his discussion will reignite a controversy that will pay attention to his attempt to provide a more sophisticated account of the character of religion.

Doug Hynd was a public servant. He has lectured in Christian ethics at Charles Sturt University and is currently undertaking a PhD in Theology and Public Policy at the Australian Catholic University.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.