‘Small but powerful: two Canberra Great War exhibitions’, Honest History, 13 April 2015

David Stephens reviews All That Fall at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, and When Hall Answered the Call at the Hall School Museum, Hall, A.C.T.

You only need to have a smattering of a classical education to recognise the story about Roman generals who were accompanied in their triumphal processions by a slave who whispered quietly to them, ‘remember you are only human’. This was meant to keep the general – as we would say today – grounded.

In Australian commemoration land during the centenary of Anzac, it is not too fanciful to see the Australian War Memorial as the triumphant one – the centre of commemorative action in the national capital – and the other national cultural institutions as rotating through the role of whispering slave. In the present case, the whispers might be along the lines of ‘there’s a bit more to war than death and glory’. The other institutions are effectively reminding the Memorial about the parts of our World War I history that the Memorial leaves out. The question is whether the Memorial has the wit to listen.

The National Portrait Gallery is running an exhibition called All That Fall: Sacrifice, Life and Loss in the First World War. The exhibition is quite small but it makes you think. The highlight for this reviewer was the display of posters, borrowed from the War Memorial but arranged in a clever way. A wall panel explains how the posters morphed from the early appeals to ‘the masculine ideal of the bronzed athletic Australian man’ and celebrations of mateship and promises of adventure to ‘desperate depictions of injured Anzacs in need of help’. Indeed they do and the change of mood is striking. Posters of women and ravaged Belgium ramp up the pressure on young men to enlist – pressure that would have been difficult to resist and which would have partly explained the relatively high Australian enlistment rate.

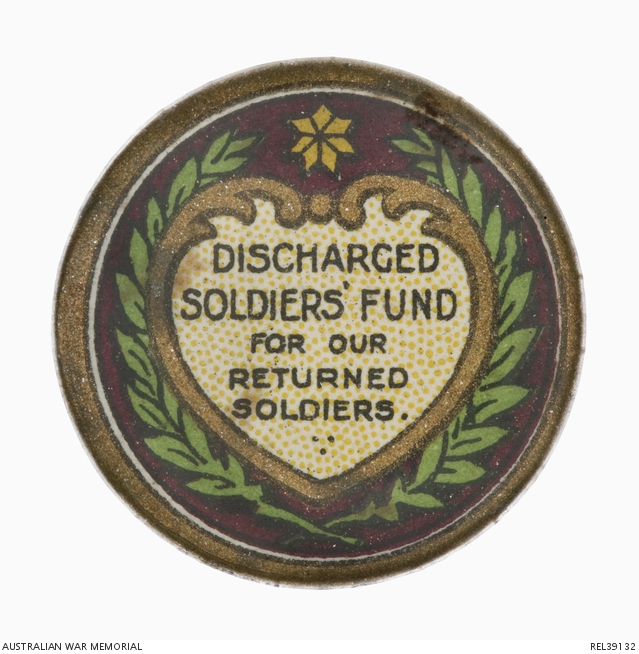

(Left) Fundraising badge: Discharged Soldiers’ Fund for our Returned Soldiers, South Australia, c. 1918-19 (Australian War Memorial REL 39132)

(Right) Volunteered for Home and Empire Cross, c. 1915-18 (Australian War Memorial REL 30976)

The title All That Fall is a reference to Psalm 145 (‘The Lord upholdeth all that fall, and raiseth up all those that be bowed down’) but the themes that emerged more starkly were how war seeks to impose unity upon nations and, at the same time, how it categorises people. We see both the brittleness of the Great War precursor of ‘Team Australia’ – it is remarkable how divided the nation became during the conscription campaigns despite the Hughesian police state and the propaganda onslaught depicted in the posters – and the building of barriers between the volunteers and the ‘shirkers’ (there was a special badge for men who had tried to enlist but were passed unfit), between those who lost family members (badges for mothers of the dead, Dead Man’s Penny medallion and certificate from a grateful monarch) and those who had to cope with wounded or limbless returned men (large photograph of prosthetic limbs). We are left to wonder who carried the greatest burden.

In the rest of the exhibition there are actors from Black Diggers talking about the experiences of Indigenous soldiers, some large photographs by Lee Grant, a crocheted tablecloth with the outline of a soldier, some quirky cartoon-like gouaches from Grace Burns, a large installation with wax and lights and a soundscape by Lawrence English with names of dead soldiers read by an adult female voice. The last is more effective and appropriate than the Roll of Honour Soundscape at the War Memorial, where the children’s voices are too small for the space and the stated ambition of the project (to help children ‘connect’ with the dead) is rather creepy.

An imaginative bonus of All That Fall is a booklet (donation five dollars) containing (in distressingly tiny print) essays by historian Pat Jalland, philosopher Raimond Gaita, photographer Lee Grant and curators Chris Chapman and Anne Sanders. Gaita’s piece is the most substantial, particularly on the inevitable tension between emotion and reason in our attitudes to war and its effects. Among many closely argued and thought-provoking paragraphs, Gaita asks this question:

But can we imagine anyone who does not care whether they have mistaken infatuation for love, jingoism for love of country, maudlin self-indulgence for grief, servility for humility or mere recklessness for courage?

A good question to keep front-of-mind in the next four years. Gaita poses others just as important. (He also spoke on ABC radio to Geraldine Doogue, who had earlier opened the exhibition.)

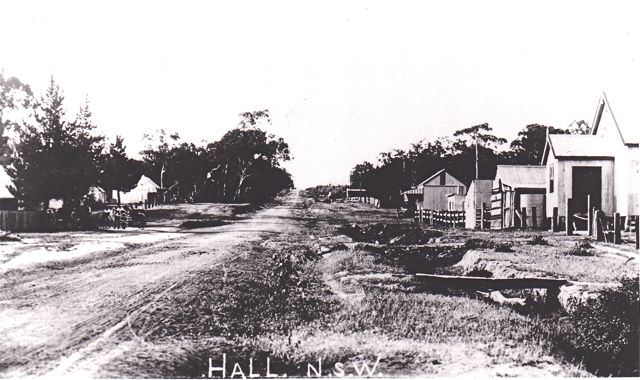

Victoria Street, Hall, 1912 (Hall District Progress Association/Hall School Museum)

Victoria Street, Hall, 1912 (Hall District Progress Association/Hall School Museum)

Meanwhile, in the village of Hall on Canberra’s rural outskirts, the Hall School Museum is putting on, at weekends during April and with funding from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, an exhibition called When Hall Answered the Call. This little museum is clearly not a national cultural institution but, like the Shire at War website down Alberton way, it is an example of what is happening in local communities to present aspects of Australia’s Great War experience.

Hall and nearby areas were settled and farmed by members of the Blundell, Crace, Kilby, Kinlyside, Shumack, Southwell and other families. Their men and women went to World War I and their descendants have put this exhibition together, using many artefacts treasured in families over decades. The exhibition gives a comprehensive picture of how a closely-knit community dealt with war. It raises individuals from the sidelines of the World War I galleries at the Australian War Memorial, with their tableaus of mass slaughter, and gives them soul and character. It encourages us to forget those bulk numbers (8709, 17 924, 61 522) and bloodthirsty and boastful percentages (killed to enlisted, killed to men of enlistment age) and look at the impact on individual human beings.

To this reviewer, the most affecting items at Hall were not the explicitly warlike ones but the domestic and workaday things like washtubs and irons, scythes and saws and binder twine, the indicators of the lives lived by mothers and fathers, brothers who drew the short straw to stay home, sweethearts and sisters. You can imagine a Shumack or a Southwell scrubbing or shearing and trying not to dwell on events on the other side of the world.

Still, there were many other exhibits, arranged with great care, including colour patches and tin hats, reproductions of cigarette cards and cartoons and grateful messages from the King, letters and postcards, some ‘female relative’ and other badges and lots of well-researched information. There might have been a bit much text here and there but people seemed to be reading it with interest. It occurs to me that a photograph of an interesting person is more likely to draw the eye to accompanying text than a massive George Lambert painting or a diorama freezing a moment in a forgotten battle.

The people at Hall had also put together an interesting video to complement the static exhibits. It nicely sidestepped the ‘Anzac as secular religion’ issue with words along these lines: ‘We Australians are not particularly a religious people but if we have a common sacred place it is here’ (cut to picture of Australian War Memorial). A lot hangs on that word ‘if’.

This reviewer’s only real beef with the displays was the use of that wretched word ‘fallen’ in a caption ‘Remembering the fallen’. They are dead, they always will be, and euphemisms like that get in the way of clear thinking about whether their deaths were worth it. War involves calculation; remembrance should, too, and the remembrance calculation should go deeper than the platitudinous ‘they died for our freedom’.

The Canberra Times columnist, Ian Warden, has written feelingly about the Hall centrepiece, the mock-up ‘Welcome Home’ dinner. Such spreads came immediately after scenes like that in the famous picture of Sapper Dunbar’s welcome. A good time would have been had by all. ‘What comes next’ would have been the unspoken question; there was an item in the Hall display about what was then called shell-shock.

The children of the district had started to celebrate the Armistice long before the rock cakes and sponges were laid out on the trestle tables at Kinlyside Hall (the Hall hall). The pupils of Weetangera primary school were in the playground when they heard the war was over. They clapped and cheered, we are told, and Mrs Clark let them all go home early. Later they all received a Peace Medal from Prime Minister Hughes and the Commonwealth Government.

What are the chances of bigger, wealthier institutions taking up the Hall challenge to look more deeply at what happens when communities ‘answer the call’? The Australian War Memorial will say that neither its charter nor its collection allows it to do justice to events beyond our overseas battlefields. The first argument is nonsense; the Memorial’s Act explicitly requires it to look at the ‘aftermath’ of wars. As to the second point, a Memorial spokesman made it not long ago when trying to justify why the Memorial steers clear of depicting the Frontier Wars, the clashes between Indigenous Australians and white settlers between 1788 and 1928.

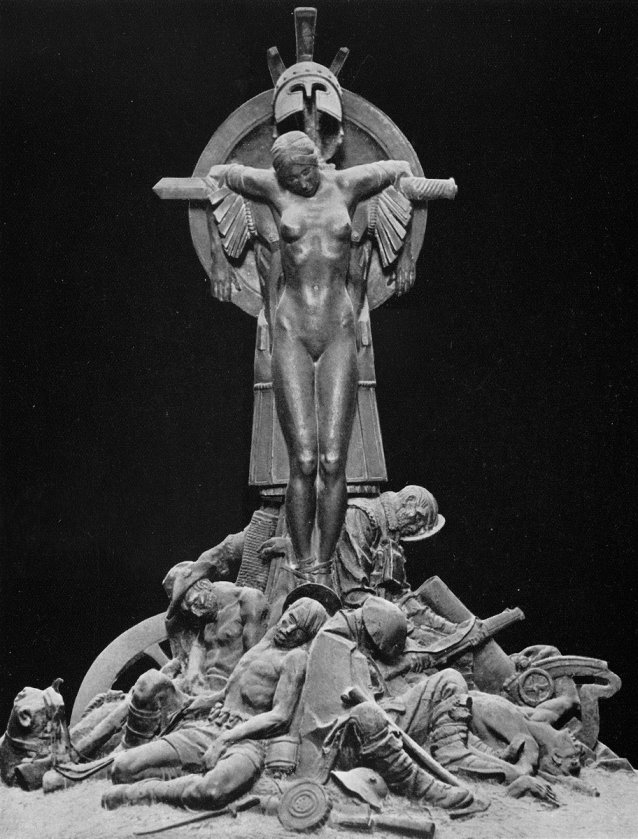

Crucifixion of civilisation, 1932 (National Portrait Gallery/Rainer Hoff)

Crucifixion of civilisation, 1932 (National Portrait Gallery/Rainer Hoff)

The Memorial could, however, spend some of the money it receives in large dollops from government and from corporate sponsors (including arms companies) to develop and present collections in new areas, rather than relentlessly repeating familiar themes. The evidence that a more nuanced view of our war history can be presented successfully is seen in the results that the other cultural institutions – and volunteers in a small village – wring from much, much smaller budgets than the Memorial enjoys.

What of the whispering slave? Hall’s call is silent at the end of April. All That Fall clocks off on 26 July, Keepsakes at the National Library a week earlier. The National Museum stepped into the chariot on 3 April with The Home Front, but for a limited time only. The rest is silence. The war is soon over for these institutions.

Meanwhile, the War Memorial’s turnstiles will keep on clicking over for its million visitors a year (including tens of thousands of subsidised school children) and it will never occur to many of these people that what they are seeing at the top of Anzac Parade is only part of what war means to Australia. Nor does it seem to occur to the management and Council of the Memorial (and to successive governments) that this venerable institution could and should explore pathways that diverge from those mapped out by Charles Bean a century ago.

The Triumph of Julius Caesar, by Andrea Mantegna 1484-92 (Wikimedia Commons)

The Triumph of Julius Caesar, by Andrea Mantegna 1484-92 (Wikimedia Commons)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.