‘Settling for less’ (review of Scates and Oppenheimer), Honest History, 13 December 2016

Michael Piggott* reviews The Last Battle: Soldier Settlement in Australia, 1916-1939 by Bruce Scates and Melanie Oppenheimer

At last the book is out. Its official genesis dates from July 2008 when the Australian Research Council (ARC) awarded joint chief investigators, Bruce Scates and Melanie Oppenheimer, funds to undertake a four-year study of the social, cultural and environmental history of soldier settlement in New South Wales, 1916-1939. It was a linkage grant, the key non-academic partners being State Records NSW (now State Archives and Records NSW) and the Commonwealth Department of Veterans’ Affairs. The grant conditions required a website, a doctoral thesis, a series of published articles, and a book ‘written for both a popular and academic audience’.

There is very little not to like about The Last Battle. Externalities first. The book is well-designed and produced. Endnotes, bibliography and index are all there. The contents page, overview provided in the Introduction, and the Part and Chapter markers combine to show clearly where the authors are taking us. Good use of section breaks and sub-headings combined with illustrative matter mean that a double page of unbroken text is a rarity. As for the editing, to my eye at least there was barely an error.

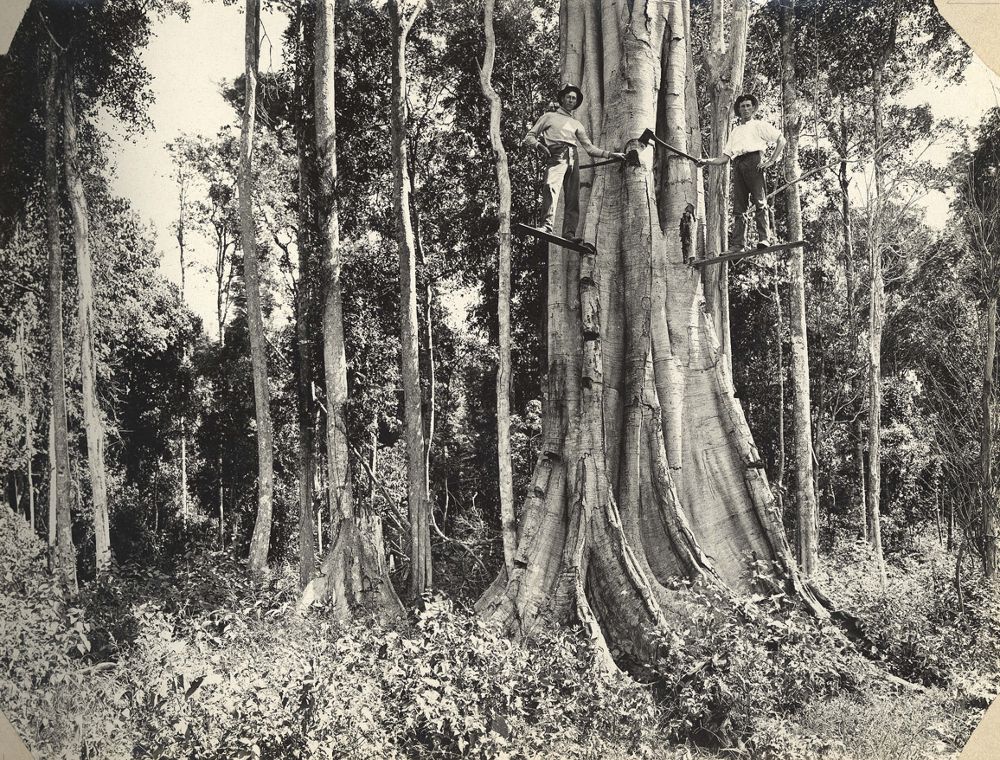

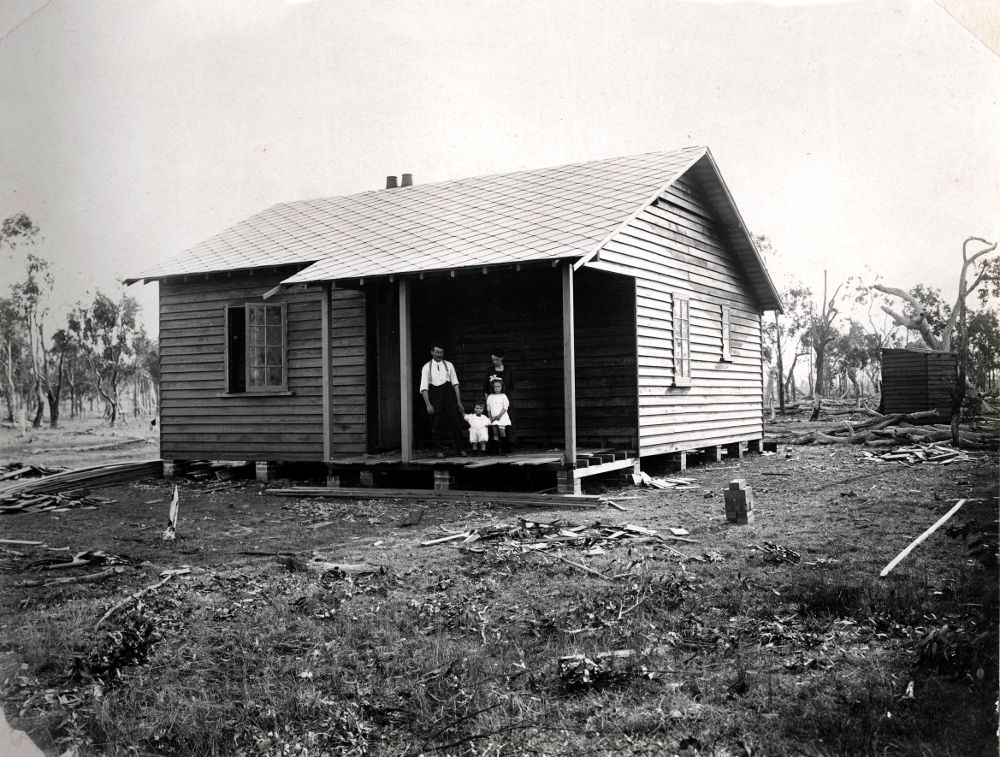

The illustrations are superb and in sufficient numbers (despite the cost, one imagines) to support the argument in the accompanying captions and text. The most telling pictures are those helping contrast, on the one hand, the hype of the independent yeoman Digger being rehabilitated by open air and physical labour with, on the other hand, the often tragic reality of fire, drought, rabbits, physical and mental handicaps, collapsing markets and mean-minded officialdom. Commendably, while the authors might have settled for images just from the collections of their partner archives, they have included reproductions of news cuttings, objects, advertisements, leaflets and posters, as well as staged and informal farming action photos from a dozen or more institutions, as well as some they themselves took.

The illustrations are superb and in sufficient numbers (despite the cost, one imagines) to support the argument in the accompanying captions and text. The most telling pictures are those helping contrast, on the one hand, the hype of the independent yeoman Digger being rehabilitated by open air and physical labour with, on the other hand, the often tragic reality of fire, drought, rabbits, physical and mental handicaps, collapsing markets and mean-minded officialdom. Commendably, while the authors might have settled for images just from the collections of their partner archives, they have included reproductions of news cuttings, objects, advertisements, leaflets and posters, as well as staged and informal farming action photos from a dozen or more institutions, as well as some they themselves took.

There was an inspired choice for the dust wrappers, Harold Cazneaux’s 1918 pictorialist print ‘Peace after war and memories’. It sums up the book’s main characters and it hardly matters who it depicts; that is, according to the Art Gallery of NSW, it may not have been a soldier settler. Just as inspired was the choice of colours for ‘A land fit for heroes?’, the website of the ARC project partner, where red, orange and brown were deployed to evoke rural NSW during a dust storm.

Now, content. The Last Battle is an important and significant book. It is not the first study of Australian World War I soldier settlement schemes – there is a reasonably complete literature survey at note 24, p. 252 – and not the first to take or indeed follow the ‘narrative’ turn in historical writing. But it is the first work to marshal many hundreds of accounts of those who experienced such schemes, accounts based on the combined riches of their individual AIF service, Repatriation and NSW Lands Department files. On these files are a wealth of documentation by officials: internal memoranda; the solders’, wives’ and others’ letters; and reports by inspectors following visits and medical doctors who had done examinations. Even with the authors’ repeated warnings that we must take care today how we interpret the files, they as historians share readings ‘against the grain’, their insights of officialdom’s mindset and the sound of the ‘emotional truth’ in the file subject’s voice.

These primary and archival accolades aside, the authors deserve real praise for including (as they had to), as well as a study of the soldiers’ misery and hardship and failure, an examination of the schemes’ underpinning ideology. They introduce us to the thinking behind the schemes at the highest official levels but also among individual inspectors and members of various tribunals and boards, and, using EP Thompson’s concept of moral economy, from the perspective of the soldiers themselves.

Scates and Oppenheimer extend us in another direction too: the experience of soldier settlers who were Indigenous Australians, who were returned nurses, and who were the spouses and children of returned men. Then, in the final chapter, about the various schemes up to 1939, a third new angle is explored: the viewpoint of those who, because they did not abandon their land, can be regarded as successful settlers.

Beyond its intense triangulated use of soldier settlers’ documentation, what makes The Last Battle so distinctive is the way history is woven from this material. Paragraph after paragraph, chapter after chapter, a point is made, then illustrated with two or three case study examples of individual soldiers’ or soldiers’ families experience. ‘Many such settlers placed their personal grievances within a formal political context’ (p. 81) is followed immediately by the story of Thomas Arthur, who farmed a block at the Tarcutta Soldier Settlement.

Soldier settlers clearing trees, Mullumbimby, NSW, c. 1921 (Wikimedia Commons/State Records NSW)

Soldier settlers clearing trees, Mullumbimby, NSW, c. 1921 (Wikimedia Commons/State Records NSW)

Often settlers’ own letters are quoted, too. Most chapters open with a mini biography or two, introducing what happened in the war and then on the land that is emblematic of the chapter theme. This is not history written via sweeping generalisations with evidence, but a telling of experience at the most personal level to support a small generalisation which implies with each new name an overall picture of generalisations: ‘Settlers across New South Wales “subsisted” on the rabbit’ (p. 127); ‘Similar stories are told right across the country’ (p. 223).

All in all, it is part Bill Gammage, part Ken Burns, and both parts are highly effective and deeply affective. The impact is to prompt anger and disbelief that anyone could have deliberately designed such schemes. These men and their families were expected to settle for less, far less, than they deserved – and had a right to expect – in return for what they had done for their country.

Unfulfilled expectations must be one of the occupational hazards of producing good history. The authentic voices of the soldier settler and his wife and other family members come through again and again in The Last Battle. But the authors mention other players, too, such as inspectors, Lands Department officials, members of pension boards, mental asylum staff, and medical practitioners. Yet, apart from a degree of personalised focus on inspectors in chapter 1, the others are unnamed and usually heartless bit-part actors.

Who were these sellers of patent medicines, the stock and station agents, the clerks in ‘the bureaucratic maze in faraway Sydney’ (p. 73), the officials in the Repat, ‘a sprawling medical and welfare bureaucracy’ (p. 146)? How should we situate them, interrogate them, apportion them agency? What are their personal stories: were any of them returned men with large families; did any stand up to their supervisors? Determining the justice of an applicant’s claim is a challenge for historians, we are told: ‘Faced with equally compelling accounts by doctors, settler and Inspector, who is to be believed?’ Then Scates and Oppenheimer rightly add, ‘And repatriation authorities faced an additional challenge. Assuming a medical complaint was genuine, how much of it was war related and what was simply congenital?’ (p. 149).

About any particular title under review small things will strike one as impressive, irrationally irritating or wholly surprising. I was much taken by Scates’ and Oppenheimer’s thoughtfulness in mentioning others. They were generous to a fault in acknowledging those who supported their research for the book and the ARC project generally. More impressive still was to actually record nine researchers’ names on the book’s title page (including Laura James and Rebecca Wheatley, who previously worked with Scates on the World War One 100 Stories project); another, Will Frances, we assume is the William Morris Scates Frances who appears many times in the endnotes and in the bibliography under ‘S’. State Records and Archives NSW adopted similar good practice, particularly noting key volunteers who helped index Lands Department files.

My irritation concerns the entirely unnecessary overreach in the book’s subtitle, Soldier Settlement in Australia, 1916-1939. As would be obvious from even a cursory look at the book’s content or even a quick scan of the index, the book is about soldier settlement in New South Wales. Hence the ARC project title and archives industry partner. Little of the NSW story had been researched before this project and, with newly-released archives and ARC funds, the authors certainly remedied that shortcoming.

The authors’ perfunctory acknowledging, especially in the introduction and final chapter, that other states had schemes, should fool no one, though the National Library cataloguers were. The non-NSW states were not the authors’ special focus and, in thus depending on secondary material, they inevitably missed titles (for example, Murray Johnson’s doctoral thesis, Honour Denied: A Study of Soldier Settlement in Queensland, University of Queensland, 2002).

Soldier settler’s cottage, Kentucky, NSW, c. 1921 (Wikimedia Commons/State Records NSW)

Soldier settler’s cottage, Kentucky, NSW, c. 1921 (Wikimedia Commons/State Records NSW)

We are left to speculate about interstate comparisons. NSW had the highest numbers of soldier settlers (9652 by mid-1936) and the most diverse types of land tenure, and was the only state to report on transfers and forfeitures. In what ways (and why) was the experience of the other 25-30 000 soldier settlers similar or different? Was the failure rate of 50 per cent uniformly spread across the states? In The Bush (2014) Don Watson puts the failure rate in Queensland by 1929 when the scheme was abandoned at 60 per cent at least (p. 387). Occasionally, the authors admit their focus is only NSW yet (sheepishly?) add ‘but most of the observations ventured here apply to schemes in other states as well’ (p. 111).

As for my surprise, Scates and Oppenheimer state that all royalties will go to the Australian Red Cross. Perhaps my reaction was naive, given Oppenheimer’s previous writing on the Red Cross, including a commissioned centenary history, The Power of Humanity (2014). Regardless of the amounts involved, this is noteworthy and commendable. As Jay Winter wrote in an insightful, and at one point slightly critical Foreword, for having now a much deeper and broader appreciation of the soldier settler experience we owe Scates and Oppenheimer ‘a considerable debt’. Because their book deserves brisk sales, so too should the Red Cross owe the authors a debt.

* Michael Piggott is Honest History’s Treasurer and a former senior archivist

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.