Andrew Richardson*

‘Jeff Grey’s character, personality and contribution are captured in this book’, Honest History, 27 November 2018

Andrew Richardson reviews Jeff Grey: A Life in History, edited by Peter Stanley

Like most (if not all) military historians based in Canberra, I knew Jeff Grey. I knew him more on a professional than personal level, and discerned very quickly that he was a towering intellect and significant force in UNSW Canberra’s military history academic cadre. I also found in him a dry humour, and his sincere passion for quality military history and rugby union was only exceeded by his affection for his family.

Grey was often cynical, occasionally irascible but always entertaining. His sudden and unexpected passing at home on 26 July 2016 sent shockwaves through the Australian military and military history community. His absence is still felt by his friends and colleagues.

Grey was often cynical, occasionally irascible but always entertaining. His sudden and unexpected passing at home on 26 July 2016 sent shockwaves through the Australian military and military history community. His absence is still felt by his friends and colleagues.

Jeff Grey: A Life in History is an unusual publication that memorialises Grey’s character, personality, and scholarly and personal contribution. Written by his friends and colleagues, it is not a festschrift, nor does it contribute new material to the field of military history. It is instead a personal printed memorial to one of the most influential Australian military historians of the last half century.

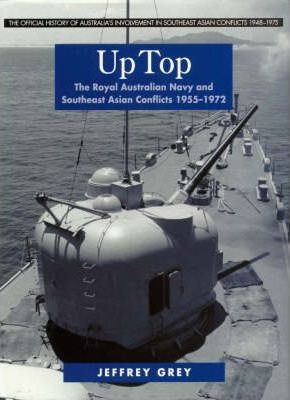

The book contains an introduction by Peter Stanley and six chapters that explore an element of Grey’s character or contribution to Australian military history. Eleanor Hancock reflects on her long period as a colleague; William Westerman looks at Grey’s legacy from a student’s perspective; Peter Dennis and Craig Stockings look at Grey’s experiences in writing official history (Malaya-Borneo and then the RAN history Up Top); Peter Stanley explores Grey’s networks and international connections as a measure of his global influence; Frank Bongiorno looks at the evolutions in Grey’s seminal A Military History of Australia across its three editions (a book of which Peter Dennis remarks, a ‘tour de force and, decades after the first edition appeared, it still has no rival in the field’) (p. vi); and John Connor covers Grey’s treatment of frontier conflict. Emily Gibbs provides a very useful bibliography of Grey’s published works, demonstrating his prolific output.

The book’s greatest value is in eschewing hagiographical pretensions. There may have been an inclination two years after Grey’s passing to look back on his career through rose-coloured glasses. That was resisted. Instead, the chapters build a picture of a man that is respectful, honest and authentic. Hancock’s article is arguably the most revealing of all contributions, providing insights into a man increasingly at odds with the corporatisation of modern universities. His gruff facade, Hancock argues, militated against promotion, and this was fed by a lack of overseas appointments (pp. 7-8). Throughout Grey’s academic career, and despite a passion for American military history, he was ‘dedicated to the scholarly study of Australian military history in particular’, ‘had no time for the ‘Anzac myth’”, and ‘mocked the tendency to exaggerate the claims of Australian military prowess’ (p. 9). Grey’s generosity for colleagues and good advice for junior academics were some of Hancock’s best memories of Grey, in spite of his growing cynicism and world-weariness (p. 11)

Westerman’s chapter reinforces both Grey’s great love for rugby and Peter Dennis’s argument from the Foreword: that context is everything (p. vi). In trying to understand trends and developments in national histories, Grey strongly believed that a study of the military should be part of that contextual appreciation. ‘[G]iven the enormous potential of war to bring about change and the prevalence of armed conflict throughout history’, Westerman writes, ‘an appreciation of warfare and the military was a necessary part of understanding complex transnational issues’ (p. 23).

Bongiorno took the same approach, noting that Grey ‘believed that military history should have a place in the wider conversations about Australian history’. (p. 61). Military history’s absence from Australian universities outside of Canberra is a key point in Bongiorno’s chapter, prompting a discussion on the state of military history within Australian universities (and Grey’s place in it). The corollary, of course, has been the preponderance of journalists producing military history ‘of varying quality’ (p. 67). In this context, Grey’s passing is even more distressing.

Peter Stanley’s chapter was drawn from an unusual premise but one that made sense on reading, as the chapter explored Grey’s evolving networks and affiliations through the attributions and acknowledgements in his many works. Through this method, Stanley was able to link Grey’s professional relationships with his burgeoning international engagement, which culminated in his being the first non-North American President of the Society for Military History (a position he held up to his death). As Stanley so succinctly summarises, ‘Jeff was a military historian who happened to be an Australian rather than an Australian military historian’ (p. 59).

Peter Dennis and Craig Stockings’ chapter explores Grey’s approach to writing official history. It describes his philosophical premise – ‘a careful analysis of “why and how”, interwoven with a narrative thread’ (p. 33) – and the friction that arose from his trying to include the use of signals intelligence from operations in Borneo; it had to be removed. The chapter also discusses the writing of Up Top and the challenges Grey faced in writing an engaging narrative for naval operations during Southeast Asian Conflicts, as well as the volume’s critical reception. But Grey stayed true to the maxim of providing a record of what was done in the name of Australia and commemorating the deeds of those involved (p. 35).

Peter Dennis and Craig Stockings’ chapter explores Grey’s approach to writing official history. It describes his philosophical premise – ‘a careful analysis of “why and how”, interwoven with a narrative thread’ (p. 33) – and the friction that arose from his trying to include the use of signals intelligence from operations in Borneo; it had to be removed. The chapter also discusses the writing of Up Top and the challenges Grey faced in writing an engaging narrative for naval operations during Southeast Asian Conflicts, as well as the volume’s critical reception. But Grey stayed true to the maxim of providing a record of what was done in the name of Australia and commemorating the deeds of those involved (p. 35).

John Connor’s chapter explores in detail Grey’s treatment and refinement of ideas on frontier warfare in his A Military History of Australia. The maturing of Grey’s opinions reflected a greater appreciation of the impact of Indigenous dispossession and a realisation of the geographical spread and effectiveness of Aboriginal resistance (p. 85). Though Grey never wrote widely on the Frontier Wars or Indigenous resistance beyond that, Connor argues that ‘it appears that having made his own significant contribution on this subject, he left it to others to make their additions to the field’ (p. 85).

The book has beautiful production values with excellent quality paper stock, crisp printing and restrained design. The work is likely to have limited interest (and readership) outside of those who have a curiosity about the author of a string of highly regarded works, or those who personally knew Grey. The lack of international author contributions is vexing, too, considering the frequent comments in the book on Grey’s international esteem and his wide global network. Such additions would have greatly enhanced the value of the work and provided perspective on Grey’s contributions in the international field of military history. In totality, though, this highly revealing work was far more honest about Grey than I considered it might be. Still respectful, it exposes Jeff Grey the human being alongside the outstanding scholar he was.

* Andrew Richardson was an historian at the Australian Army History Unit for 11 years and is now at the Australian War Memorial working on the official histories of operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and East Timor. For Honest History, he reviewed two books on the Battle of Hamel. At the time of writing, a limited number of copies of the book under review were available free of charge from the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, UNSW Canberra.