‘Retracing Kokoda: in defence of historical revisionism’, Honest History, 4 August 2014

Somehow, ‘revisionism’ in military history has been turned by some people into a dirty word. Since when did the self-evidently rational process of ‘revising’ or ‘reviewing’ become objectionable?

We often find that when a new book offers a new (usually more critical or less glorious) interpretation of a particular campaign, its author is condemned for his ‘revisionist’ views, as though this were a bad thing. The implicit assumption is that we have one version only of each story; that we already know everything there is to know; that we have the story ‘sorted’. No new information, please! This is complacent and defensive in equal measure. On the contrary, historians all over the world revise things all the time.

A review of my previous book, Darwin Spitfires, criticised me because, it was alleged, I made some judgements. The reviewer justified this criticism by citing a supposed historical rule which in effect means that, if a historical personage is dead, then he cannot be criticised by later historians; in this case, the commanding officer, Clive Caldwell, was allegedly immune from criticism, 70 years on, because he had died and had no ‘right of reply’.

Sappers of 2/6th Field Company, Royal Australian Engineers, felling trees, Kokoda, September 1942 (Australian War Memorial 026715)

Sappers of 2/6th Field Company, Royal Australian Engineers, felling trees, Kokoda, September 1942 (Australian War Memorial 026715)If this rule were true, then there would not be much to write about in books on Waterloo, Agincourt, Gettysburg, not to mention El Alamein and D-Day! And it would be particularly bad news for biographers of Churchill, Montgomery, Rommel, MacArthur, Haig, et al! However, a stocktake of the bookshelves at any bookshop would prove that there is no such rule – because no-one follows it. In fact, what historians do is exactly what this reviewer criticised me for: they make judgements and assessments, about people both living and dead, and about the events in which those people were involved.

Historians make such judgements on the basis of evidence and new evidence comes up all the time. Just because something happened 70 years ago does not mean that all the available evidence has already been taken into consideration by the authors who have documented the story to date.

To give one example, my own Darwin Spitfires was the first book on the 1943 air combats over Darwin to be based upon the pilots’ combat reports, despite these having been available in the archives for public viewing for decades. Because I was using ‘new’ evidence, I had to re-assess the story and to make new judgements in the light of this new information. To that extent, the resultant book was revisionist, in that it challenged previous orthodoxies which had now been revealed to be inadequate; instead of these received views, it set forth a newer, better version of the story that was more consonant with the fuller evidence.

Another aspect of a historian’s trade is to take into account existing research and publications. For example, new biographers of Churchill will do a discerning read of previous biographers’ work before putting their final ideas together. Similarly, historians of Waterloo will read previous histories before they write their new one. Each historian thus stands upon the shoulders of those who go before him or her.

For most historians, it is not enough to present books which rehash the ‘same old, same old’. Instead, they typically seek to uncover something new. For myself, I can’t claim that my Kokoda Air Strikes uncovers much that is genuinely new; it certainly rests upon a stack of previous books. It is, however, through the book’s conscious attempt to synthesise these earlier works that it offers something ‘new’, seeking to ‘value add’ by actively engaging with the findings of previous research. I found that many people had written on a range of aspects relating to this campaign, documenting an array of information, facts, events, insights and experiences, but that much of it had been read only by special interest readers. My job was to interconnect all this research and information, bringing it together in a single narrative. I thereby presented some material which will be ‘new’ to most readers.

War Loans and National Savings Campaign poster, c. 1942 (National Museum of Australia 1995.0026.0003)

War Loans and National Savings Campaign poster, c. 1942 (National Museum of Australia 1995.0026.0003)

Not all authors share my enthusiasm for the new. Indeed, there is a tendency for historians to sometimes disregard published evidence, seemingly being content to re-present the same old view. I will give one example from Darwin Spitfires. The Spitfire pilots were awarded credit for 70 Japanese aircraft shot down during the fighting over Darwin in 1943. Research based on Japanese records published in 1981, however, showed that the evidence points to only about 20 Japanese losses.(1) Up until as recently as 2011, Australian authors have quoted the original ‘kill’ figures without qualification. If it is revisionist to follow the evidence and amend previously-believed orthodoxies, then revisionist it has to be.

The reuse by some authors of long-disproved versions of events (for example, that the Darwin Spitfire pilots shot down 70 Japanese planes) is puzzling and disappointing. It may be that one of their motivations is to tell an uplifting story, to use military history as a source of inspiration for contemporary readers. This is understandable. Who wouldn’t want to write such a story? Particularly when it must boost book sales!

In search of just such an upbeat angle for my Darwin book, I sought evidence of crash sites in the Northern Territory. I was attempting to find evidence to support a higher total of victories by the Spitfire pilots. This line of enquiry proved disappointing. Indeed, a 2011 book by an authority on the subject presented evidence for only a very small number of crash sites for Japanese aircraft in the Top End. Because evidence was so lacking to support anything like the claimed total of 70 kills, I was forced to conclude that the Japanese loss records were a lot closer to the truth than the Spitfire Wing’s claims. Sometimes facts are inconvenient, but it is facts that historians must deal with and make judgements about.

Facts don’t have to get in the way of a good story, but a good story is just that – a story – if it doesn’t take the facts into account. There are many facts in military history: dates, times, numbers, units, casualties, results. Only once the historian has established the basic numerical reality behind particular operations, combats and campaigns does it become possible to form valid judgements and assessments.

I had to feed a broad range of such facts into my new book, Kokoda Air Strikes. Many authors had already written good stories about Kokoda and Milne Bay. Although there is more than one narrative about this campaign (those of the Australians, the Americans, the Japanese, the Papuans) it is the Australian Army’s story which holds the most privileged place in the telling and which is most enshrined in folklore and symbolism. This story is Australian-centred and focussed upon the jungle fighting against waves of Japanese infantry. But there is the air force story too; this is American-centred and focussed on the threat from the formidable Japanese ‘Zero’ fighters.

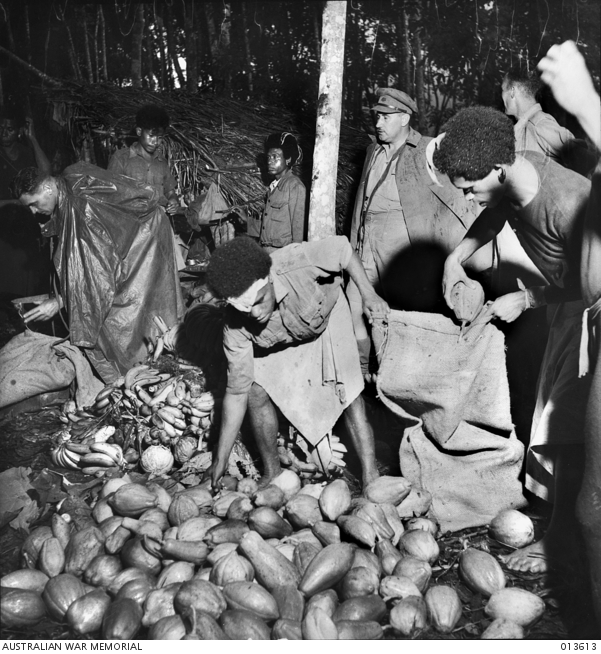

An Australian officer in charge of the natives buys fruit at a village, Kokoda, November 1942 (Australian War Memorial 013613)

An Australian officer in charge of the natives buys fruit at a village, Kokoda, November 1942 (Australian War Memorial 013613)

The predominant narrative of Kokoda fits neatly within a traditional story framework that would be instantly recognisable to any reader of both military history and fantasy novels: a small band of warriors stand before the might of a larger, better-prepared force and, despite being outnumbered, beat the enemy through little more than the superior mettle of the warriors themselves.

In their separate telling of their own parallel New Guinea story, the Americans have represented their airmen as similarly under-prepared and outnumbered, but they triumph over their more numerous and more experienced Japanese opponents through little more than their rugged individualism, their ‘can-do’ attitude and their own innately superior virility.

This way of framing the story, ironically enough, has a great deal in common with the Japanese military ethos of the period, according to which the key determinants of success in military operations were not prosaic matters like numbers, supply, or even firepower, but rather the martial ardour of the men themselves. To that extent, it must be said that the Australian and American purveyors of these archetypal stories are sitting in bad company.

For the Japanese, a romantic view like this was perhaps excusable, for the fundamental reason that, recognising the superior material strength of the United States, they had always expected to be outnumbered. In attacking China, the United States and the British Empire all at the same time, Japan had knowingly doomed itself to fighting a large war at a numerical inferiority. Given this, what else could they do but trumpet the supposedly unquenchable combat zeal of their soldiers, seamen and airmen?

There is no such handy excuse available for the martial romanticism of the Australians and Americans. The campaign in New Guinea offers a classic case of busting the myth. Port Moresby was the critical objective in the Southwest Pacific, without possession of which the Japanese campaign was doomed. Despite a clear recognition of the crucial importance of this objective, the Japanese kept committing only the equivalent of a reinforced Brigade, both along the Kokoda Track and at Milne Bay. Both of these thrusts were pushing up against the equivalent of a Division, both at Port Moresby and Milne Bay.

Contrary to the traditional telling of the story, therefore, we find that the evidence from the Japanese side indicates a half-cocked venture fought with half-measures. As Williams has shown, the numerical relationship of the two infantry forces fighting along the track was one of rough parity. The casualties inflicted and suffered were also on a par, leaving us to conclude that one Australian infantryman was worth … well, one Japanese infantryman. It is distinctly odd that anyone would expect anything else, given the emphasis placed in this story tradition upon the unpreparedness of the Australians, on the one hand, and of the vast experience and preparation of the Japanese on the other. In this context, the Australians’ achievement of a roughly 1:1 exchange ratio in jungle fighting along the Kokoda Track must be seen as a highly creditable performance.

City of Sydney National Emergency Services supervisors, 1942 (Flickr Commons/Blue Mountains Library Local Studies Program)

If we now turn our eyes to the sky, the subject of my book, Kokoda Air Strikes, we find that a similar pattern applies. Despite the acknowledged vital importance to the Japanese of conquering Port Moresby, they committed, throughout the campaign, a supporting air force consisting only of the equivalent of one fighter group and one bomber group or about 30 fighters and 30 bombers. Considering that by May 1942 the Americans already had several times this number of modern combat aircraft in Moresby and Northern Queensland, this force allocation by the Japanese looks half-hearted and miserly in the extreme. Usually, the Allied fighter pilots found themselves up against a similar number of enemy fighters, whether in the skies over Moresby or over Lae. Once again, the numerical relationship is one of parity, not Japanese preponderance.

What then should we conclude? It turns out that the Allies successfully defended Port Moresby in 1942, not because their men were better or braver or tougher than their Japanese opposite numbers, but because they ended up bringing to the campaign more realistic plans, better logistics, better supplies, more men, more machines and more firepower than the Japanese did. Conversely, the Japanese lost because they persisted with unrealistic plans, inadequate logistics, inadequate numbers, too few machines and consequently insufficient firepower.

There is nothing for us to be ashamed of in winning through the achievement of a preponderance of force. That is the basis of good generalship and it is the way Western armies have won their wars for centuries; examples could include the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Allied victory on the Western Front in 1918, victory over Rommel in North Africa in 1942, and in Normandy in 1944. It turns out that New Guinea was little different in its essential arithmetic. We won because our people were more practical, provided better back-up, and made sure of our wins by piling up the numbers against the opposing side. What’s wrong with that?

Anthony Cooper is a Brisbane school teacher. He is the author of HMAS Bataan, 1952 (2010), Darwin Spitfires (2011) and Kokoda Air Strikes (2014), published by NewSouth.

Note

(1) Christopher Shores, ‘The Churchill Wing: a radical reassessment’, Air Classics, 17, 4, 1981, pp. 12-19.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.