David Reid*

‘Reconciliation, please, but don’t mention the war’, Honest History, 6 May 2015

I pen this as a descendant of a Scottish surgeon who came by ship to Terra Australis 195 years ago. His son, who arrived with him aged 10, wrote a memoir of his experiences in the colony from a boy in 1820 to an old man in 1905. It’s quite a tale encompassing convict reminiscences, bushrangers, exploration, pastoral expansion and pre federation politics. It’s a good read, put down in the third person by JCH Ogier in 1905. It’s also a historical document enshrined in the National Library, a fact which, in my family’s history, has always been a source of pride yet to me a haunting reminder of what effectively has developed into a sad national cover-up.

I’m referring to page 30 of this memoir. I’m reminded somewhat of a John Cleese skit where he exclaimed, ‘don’t mention the war’, when confronted by German guests. Strange analogy you might think but it’s triggered by a closing paragraph by great-great-grandfather on page 30, describing an encounter with an Aboriginal group which, like groups across the known and unknown colony, was resisting pastoral expansion into its traditional homelands.

We at last reached the hut without any further attempt at molestation, and of course immediately on reaching the hut all armed ourselves. It is not for Mr. Reid to describe what followed, but there was soon a scatterment of our sable foes.

Don’t mention the war. But don’t mention it not just to ‘the sable foe’ but to anyone. In some respects, Australians embraced the events of Gallipoli to wash away the collective conscience of atrocity by a victorious invader, at a time when that collective conscience was still taking hold in a newly federated white Australia.

Don’t mention the war. But don’t mention it not just to ‘the sable foe’ but to anyone. In some respects, Australians embraced the events of Gallipoli to wash away the collective conscience of atrocity by a victorious invader, at a time when that collective conscience was still taking hold in a newly federated white Australia.

The silence has continued for the following century. In fact it’s no longer ‘don’t mention the war’, it’s ‘what war?’, the Australian perception that for over a century Aborigines somehow simply ‘left’ their homelands as ‘Australia expanded’.

Confirmation of the contrary comes from ‘Frontier’, a 1996 documentary, made by the ABC. This film is nearly 20 years old. It is not new knowledge. According to the ABC library sales promo for the film:

Frontier is considered television’s first comprehensive account of Australia’s hundred and fifty year land war. Between 1788 and 1938, thousands of whites and tens of thousands of blacks died in racial violence across the continent. Frontier is compulsive viewing for everyone interested in Australia’s national debate on reconciliation.

Clearly, not enough of us were compulsive viewers either then or since. Not enough of us gave a toss about reconciliation.

The Frontier Wars have become such a historical elephant in the room that they effectively prevent meaningful reconciliation with Australia’s First Peoples. One could say the silence is deafening. The belief in ‘nothing here but bush’ denies a truth which remains a constant source of anguish to the descendants of what became a vanquished people, a people still struggling to recover the sparse strands of their culture that are left to study.

Even in this cheap digital age stored archives of Indigenous film and sound recordings are perishing at an alarming rate through lack of funding. All gone within a decade, according to Professor Dodson.

It’s time our true colonial history was embraced. Lasting, genuine reconciliation demands it. The ‘black armband’ and ‘white blindfold’ views of history need to refocus on a factual narrative. This narrative, no matter how disturbing it is to the Australian collective conscience, may lead to some form of accurate appreciation of who we are and how we became so.

As I read the full story today, I’m sure great-great-granddad couldn’t appreciate the outcomes of his empire building. Nor could he envision the need now for a national First People’s institution to remember his sable foe. But that’s what is required: an institution of learning, preservation and history, incorporating a memorial of the resistance to colonial invasion.

Perhaps Onyong of the Ngambri in Canberra could suggest an appropriate site. His mob roamed 500 strong (counting only the men) when the Limestone Plains were discovered in 1823. Onyong was later shot in the leg by Henry Charnwood, apparently for spearing cattle, and ended up dying in a tribal dispute circa 1840s when his mob, at a Queanbeyan blanket issue, numbered just 46.

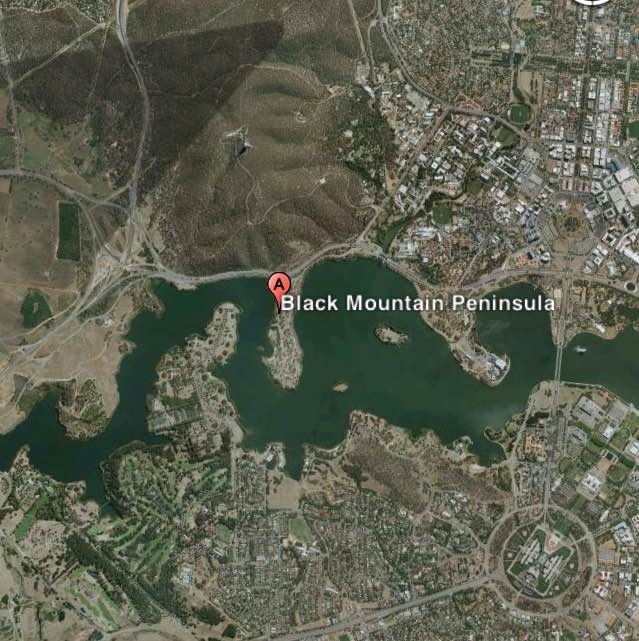

The appropriately named Black Mountain (Black’s Mountain) peninsula is a spur of Canberra’s Black Mountain, now surrounded by Lake Burley Griffin. It is also a documented nineteenth century corroboree ground. Currently a recreation reserve, it would form an admirable addition to the range of national institutions encircling the lake. I’m sure the ACT Government would give it up cheap.

The appropriately named Black Mountain (Black’s Mountain) peninsula is a spur of Canberra’s Black Mountain, now surrounded by Lake Burley Griffin. It is also a documented nineteenth century corroboree ground. Currently a recreation reserve, it would form an admirable addition to the range of national institutions encircling the lake. I’m sure the ACT Government would give it up cheap.

We spend $300 million celebrating the history of Anzac to appreciate the sacrifice of 60 000 lost lives. In a cathedral-like national institution we venerate those killed. We annually worship at the tomb of the Unknown Soldier. All of this to commemorate a war lasting four years. Yet we deny a colonial war of expansion that raged for over a century.

The magical but as yet elusive goal of meaningful reconciliation hinges on our confronting a suppressed history. Respect will be gained not from expressions of regret but from acknowledgement of truths. History needs to play its part in that.

* David Reid is a Canberra-born father of four, grandfather of two and ex-public servant who believes a more harmonious integrated national identity will form with the truthful telling of history.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.