‘Shades of the Great War are missing in this nicely packaged offering from Adelaide’, Honest History, 4 April 2018

Peter Stanley reviews Robert Kearney and Sharon Cleary, Valour and Violets: South Australia in the Great War

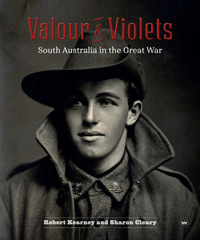

The centenary of the Great War has seen several fine histories of the war’s experience and effects on individual states, notably Michael McKernan’s book on Victoria and the war and Naomi Parry, Brad Manera and Stephen Garton’s on New South Wales. South Australia’s contribution, though handsomely produced by Adelaide’s Wakefield Press and endorsed by the (former) Premier and state Minister for Veterans’ Affairs, Jay Weatherill, is by comparison something of a disappointment. While the book is copiously illustrated with photographs and other images (many of which appear for the first time), and it gives detailed accounts of individuals, communities and units from South Australia, its luxurious production values sadly are not matched by a text of comparable quality.

To be fair, there is much of interest in the chapters (again, some of it published for the first time), but the bulk of the book refers to the experience of South Australian men overseas in the Australian Imperial Force; there is almost no reference to the ‘other’ army, the Militia. Some of the new material enriches our understanding of the way Australians experienced the war. For example, Kearney and Cleary relate how, when patriots in Waikerie proposed renaming Pflaum Street ‘Chinnery Street’ after a local man killed at Fromelles, Chinnery’s father declined the honour, pointing out that several Pflaums were also serving on the Western Front, where two of them died. Other stories – the book abounds in ‘personal stories’ to the detriment of more coherent analysis – are just as illuminating.

To be fair, there is much of interest in the chapters (again, some of it published for the first time), but the bulk of the book refers to the experience of South Australian men overseas in the Australian Imperial Force; there is almost no reference to the ‘other’ army, the Militia. Some of the new material enriches our understanding of the way Australians experienced the war. For example, Kearney and Cleary relate how, when patriots in Waikerie proposed renaming Pflaum Street ‘Chinnery Street’ after a local man killed at Fromelles, Chinnery’s father declined the honour, pointing out that several Pflaums were also serving on the Western Front, where two of them died. Other stories – the book abounds in ‘personal stories’ to the detriment of more coherent analysis – are just as illuminating.

The ‘violets’ in the title refers to the remarkable phenomenon of the Cheer-Up Society, a voluntary organisation peculiar to South Australia in both world wars, which saw immense commitment from the civilian community as a whole, but especially of the middle-class patriots of Adelaide. Mostly women, they gave of themselves unstintingly, working long hours, voluntarily and for years on end. Valour and Violets deals extensively with the Society’s story and, as you might expect, with the tensions between the state’s ‘German’ and ‘British’ communities.

But it is clear that the authors’ main interest is on the battle-front and not on what Professor Melanie Oppenheimer, in the book’s foreword, anachronistically calls the ‘home-front’. (This term was not in use in Australia until right at the end of the war, and then to refer to Germany.) The pages devoted to the war in South Australia itself are helpfully on violet-tinged paper, but they often deal with military matters – the raising and reinforcement of units, for example – rather than the full civilian experience of war. The Great Strike of 1917 does not even feature and, tellingly, one of the most notable South Australian volunteers, Adelaide Miethke (organiser of the Children’s Patriotic Fund), is only briefly mentioned and then mis-named and indexed as ‘Mietke’.

Kearney and Cleary commendably strive to include the experiences of women, children and Indigenous South Australians, but the overwhelming impression is of an essentially old-fashioned book of military history, with civilian and social history relegated to the margins. And, unfortunately for a book on the entire state, readers from Mount Gambier, Ceduna, Port Pirie, Whyalla, Port Augusta, Quorn or Gawler will find no reference to their towns in the index, and the only ‘Port Lincoln’ named is a troopship.

The book’s problems surely began with the choice of authors. Robert Kearney is best described as a war buff – supposedly the author of six books, though only three are in the National Library’s catalogue – who has got lucky: he is mostly interested in the ‘valour’ of the title, and is surely responsible for the book’s undue emphasis on the operational side of the story. While 35 000 South Australians saw service during the Great War, they represented less than 10 per cent of the state’s population, but take up about 90 per cent of the book.

The contribution of ‘communications specialist’ Sharon Cleary seems to have involved editing: she is employed by Veterans SA (the government department) as manager of the Anzac Centenary Coordination Unit. The result is an attractive book that fails to fully deliver on its promise to tell the story of ‘South Australia in the Great War’; it really deals with ‘some South Australians, mostly men who fought, in the Great War’. Had the state’s Anzac centenary commission given the job to a professional historian more skilled in integrating the contending aspects of a complex but compelling story the result might have justified the stiff price asked for what is ultimately a nicely produced book of missed opportunities.

As a supporter and practitioner of Honest History, I feel obliged to disclose that my disappointment with Valour and Violets is partly fueled by the realisation (when I looked into the book’s bibliography) to find that, though I am a former South Australian, not one of the several books I have published on the Great War is included. Having told new, specifically South Australian Great War stories in Quinn’s Post (on Light Horsemen at Quinn’s), Bad Characters (on badly behaved South Australian soldiers), Digger Smith and Australia’s Great War (on the Cheer-Up Society’s women volunteers and many others), Lost Boys of Anzac (on the first South Australians to die on Gallipoli), The War at Home (on South Australian indigenous communities), and The Crying Years (where I got Miethke’s name right), I am perhaps understandably annoyed that Robert Kearney’s research has managed to miss every one of those original contributions.

I am not alone. The authors also omit relevant books by historians actually named in the book’s Acknowledgments, such as another former South Australian, Meleah Hampton, whose Attack on the Somme (2016) is also unjustifiably ignored.

Violet Day for wounded soldiers, ‘promoted by the Cheer-Up Society’, 10 July 1915 (Anzac Centenary SA Govt)

Violet Day for wounded soldiers, ‘promoted by the Cheer-Up Society’, 10 July 1915 (Anzac Centenary SA Govt)

That admission of mine may lead you to discount the criticism of the preceding paragraphs, but I am sure that, if you seek a rounded presentation of the full impact of the Great War on the people of South Australia and their communities, sadly, despite its lavish appearance, Valour and Violets gives an inadequate account. One of the lessons that the centenary of the Great War has reinforced is that it is no longer acceptable for a book supposedly about the people of a country, state or district at war to deal largely with those few of its population who served in uniform overseas.

Professor Peter Stanley is Research Professor at UNSW Canberra and Past President of Honest History. He is one of Australia’s most productive historians of Australia’s Great War, the subject of eleven of his 32 books.

Hello Helen

Thanks. I’m sure you did enjoy reading many of the stories in Valour and Violets. But I wasn’t arguing that it should have been written in ‘academic language’. I was pointing out that it misrepresented the experience of the people of South Australia because the selection of stories was skewed in favour of the battlefield, and that it left out large portions of the state’s people. I’m no fan of ‘academic language’. I would like to think that my books are accessible and popular – indeed, most of my ‘Great war’ books – the ones I mentioned – were specifically aimed at non-academic readers. My point was that this book sells the history short by focusing unduly on only one aspect of the experience of the people of SA.

Peter Stanley

One of the many reasons I enjoyed this book is because it is written for the everyday person, not for the Academics or in their language. It’s for us… the people, just as the majority of men and women who served in WW1 were not academics.

Full of interesting insights into the era, and particularly the home-front. Things I didn’t know. Beautifully presented. Well done Cleary and Kearney!!