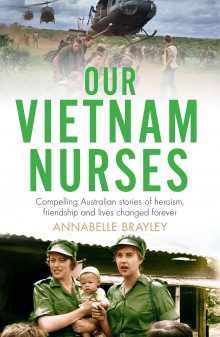

‘Our Vietnam nurses’ stories should have been told before this’ (review of Brayley), Honest History, 15 June 2016

Pamela Burton reviews Annabelle Brayley’s Our Vietnam Nurses.

It is refreshing to read stories of heroism by those who travel to war zones to save lives rather than to take them. Annabelle Brayley’s Our Vietnam Nurses (Penguin Random House Australia, 2016) is about saving lives.

The experience of Australian nurses in the Vietnam war has not been widely published, prompting a study in 2001 of Australian Army nurses who served in Vung Tau, entitled ‘The wartime experience of Australian Army nurses in Vietnam 1967-1971‘, by Biedermann, Usher, Williams and Hayes, published in the Journal of Advanced Nursing. That study concluded that the vast majority of the nurses sent to Vietnam knew little about the type of work or the environment into which they were entering and were, therefore, clinically unprepared. The study also revealed that, although the nurses adapted professionally, their memories of their experiences have affected many personally.

The experience of Australian nurses in the Vietnam war has not been widely published, prompting a study in 2001 of Australian Army nurses who served in Vung Tau, entitled ‘The wartime experience of Australian Army nurses in Vietnam 1967-1971‘, by Biedermann, Usher, Williams and Hayes, published in the Journal of Advanced Nursing. That study concluded that the vast majority of the nurses sent to Vietnam knew little about the type of work or the environment into which they were entering and were, therefore, clinically unprepared. The study also revealed that, although the nurses adapted professionally, their memories of their experiences have affected many personally.

Brayley’s collection of stories confirms those conclusions. The book brings a true-life understanding of the experiences, not only of our army nurses but also of those RAAF nurses who were based at Butterworth Air Force Base in Malaysia to care for soldiers wounded in Vietnam and who flew medivacs into Vietnam to evacuate Australian casualties from Saigon and Vung Tau.

The book is reminiscent of Siobhan McHugh’s Minefields and Miniskirts, first published in 1993: an account of Australian women risking their lives in Vietnam in a war that did not belong to them. Like many soldiers, many nurses signed from a youthful sense of adventure but with no real idea of the horror that they would confront in being exposed to guerrilla warfare and of the alien culture and landscape into which they would be dropped.

Brayley’s 15 separate but interlinking stories reveal the lack of briefing nurses received on the overcrowded hospitals and poor conditions they were expected to work in. The nurses had no training about nursing in a tropical climate in a contemporary war zone, were told nothing about cultural and religious differences around health and healing and, sadly, missed out on debriefing on their return. Yet the nurses cheerfully accepted the situations they found themselves in and made do with inadequate medical supplies and the non-delivery of medications ordered and paid for, while, in order to care for their patients, they coped with terrifying events that threatened their own lives.

The book adopts the format of Vietnam War Nurses, the edited stories of 18 American nurses (edited by Patricia Rushton and published in 2013) although the Australian nurses’ voices are indirect, Brayley narrating their stories from interviews she conducted. Nevertheless, she captures the young nurses’ diverse emotional reactions: joy at helping a soldier recover from an amputation; terror at narrowly avoiding being killed; the horror of tending to bloody maimed bodies; frustration having to deal with a range of medical conditions, including tropical diseases and bacterial skin infections, for which the women had no training.

Brayley’s own input is minimal, historical research and contextual material confined to a few pages at the back of the book headed ‘Background and timeline’. She faithfully tells the stories, without embellishment. However, the reader is left wondering, for example, about the truth of the ‘briefing’ given to one nurse, that if, when flying over Vietnam, the aircraft was shot down, it was up to the pilots to shoot the nurses so they wouldn’t be taken prisoner. The nurse used to check out the pilot on every flight, thinking he might be the one who’d have to shoot her. The point of the story is that the young nurse always believed the statement to be true. That particular nurse spoke to no one to question this at the time because she had been sworn to secrecy about her work.

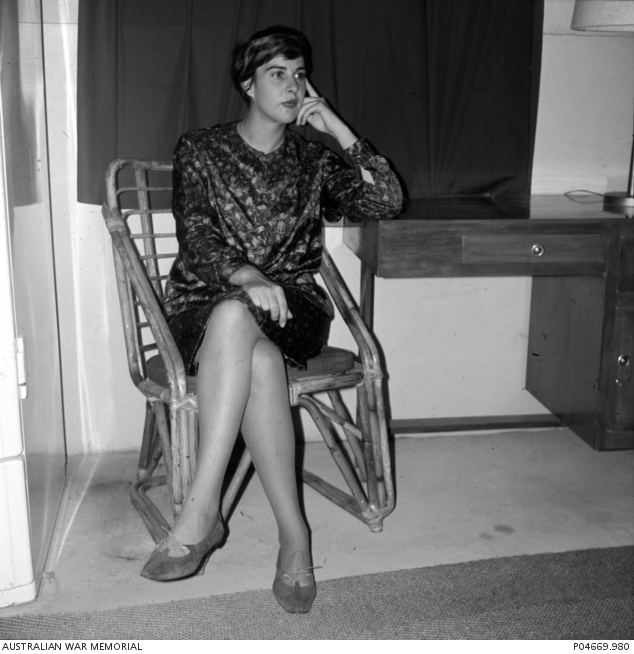

Lt Margaret Tony in her quarters, Phuoc Tuy, 1967 (AWM P04669.980/DS Gibbons)

Lt Margaret Tony in her quarters, Phuoc Tuy, 1967 (AWM P04669.980/DS Gibbons)

Secrecy surrounded everything, except when it came to government propaganda. All of the nurses were told that they could tell no one about their work in Vietnam or their deployment to the medivac team flying in and out of Vietnam. Some felt betrayed when they learned that they were identified at home in film clips or radio announcements. One, instructed by her supervisor to tell no one outside the RAAF that she was going to Vietnam, opened a letter one day from her shocked mother who had seen her on television loading patients in Vietnam. The nurse had no idea she’d been filmed or that the film would be broadcast as news back home. Another, silent about her posting, heard her name on the radio in the presence of her parents in 1966, just before she left for Vietnam. There was a public fanfare about the nurses’ departure, presumably encouraged by the army to help reassure the families of young men who had been called up in the national service ballot and were bound for Vietnam.

The stories provide a moving account of sometimes humorous, more commonly traumatic, experiences. But the horror of war is not confined to the ghastly sights and situations that confront nurses and civilians working and living in war zones. Brayley’s tales follow the nurses home to see how they fared. Though they had served their country, many suffered on returning home. They were not honoured with the status of war veterans. These were the days of conservatism and societal prejudices that discriminated according to gender and jobs in valuing the services performed by Australian men and women.

Nurses who married when they returned home were forced to resign their commissions. The ban on married women working in the services remained in place until 1978. More hurtfully, nurses – men and women – were not regarded as having been on ‘active service’, or the secrecy surrounding their service made it too difficult to prove that they were. One young nurse who, some years after returning to Australia had become a single mother, unable to work and support her children, applied to Defence for housing assistance, only to be told that she had not been on ‘active service’.

Some of the nurses whose stories were told reconnected over time and discovered that they all had stories of denial of their service. They banded together to put this right. One nurse, who had buried her Vietnam memories and the abysmal treatment she received on returning home, was forced to revisit her anger and pain more than a decade later. A violent storm tore down a shed on her farm. The cleanup revealed a trunk of documents including her diary and letters home. They helped her and some of her colleagues to win their argument with the Department of Veterans’ Affairs for recognition of their Vietnam service. In 1989 their service was officially acknowledged and they were awarded the Returned from Active Service Badge. By 1994 all RAAF nurses who were based at Butterworth, who flew medivacs into Vietnam evacuating Australian casualties, and who were seconded to the United States Air Force, were awarded the Vietnam Medal and the Australian Active Service Medal. They successfully applied for Gold Cards from Veterans’ Affairs.

The stories told are not only those of women. They include the dedicated work of a male medic on the front line and the experiences of young conscripts. They all tell of the futility of war and of the professionalism and commitment of those who found themselves, through one life event or another, caring for the wounded in Vietnam.

Medical evacuation, 2nd Field Ambulance, Vung Tau, 1967 (AWM ART 40580/Bruce Fletcher)

Medical evacuation, 2nd Field Ambulance, Vung Tau, 1967 (AWM ART 40580/Bruce Fletcher)

These compelling stories help us to understand what went on in Vietnam. They don’t answer our questions of why we were there or what we were trying to achieve in the longer term. What has changed? Australia still sends its troops and nurses, men and women, to other countries’ ghastly wars. Our Vietnam Nurses demonstrates that, whether war nurses believe in a political cause or not, they will give their life for others, acting selflessly in the moment of compatriotism.

Pamela Burton is a former Canberra lawyer and author of three books (From Moree to Mabo: The Mary Gaudron Story, The Waterlow Killings: A Portrait of a Family Tragedy and A Foreign Affair). She is also a member of the Honest History committee.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.