‘Mythbusting about Australians returned from Vietnam: Honest History highlights reel’, Honest History, 9 June 2015 updated

UPDATE 14 July 2015: further volume planned on medical aspects of Vietnam War service. Comment by Alison Broinowski.

UPDATE 18 June 2015: Dr Sheralyn Rose responds to this highlights reel, particularly in relation to the attitude of the RSL.

UPDATE 12 June 2015: the Vietnam Veterans’ Federation responds to this highlights reel, particularly in relation to Agent Orange.

______________

Australia 2015 is in the midst of two commemorative exercises. According to Senator Michael Ronaldson, Minister assisting the Prime Minister for the Centenary of Anzac:

The Centenary of Anzac is not just about commemorating those who fought in the First World War. The Anzac Centenary program is about a century of service: it commemorates and recognises the service of all those who have served in the Australian Defence Force over the last one hundred years.

One focus will be the Australian commitment to Vietnam from 1962 to 1975, including the idea that the soldiers Australia sent to that theatre were ill-treated on their return home. Senator Ronaldson provided an example of this theme recently:

We honour our Vietnam Veterans, and their families. We acknowledge that our nation has, in the past, not appropriately recognised their service and sacrifice. As we mark our century of service, the Australian Government is determined to ensure that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past and honour those who have served their nation.

‘The Welcome Home March, 3 October 1987: Because many men returned from Viet Nam in small groups it was not possible to have grand parades for them. When Battalions returned they usually marched through the streets of a major city but these often attracted the rabid rat bag element of the Anti War, Anti Conscription, Anti Government and Anti Anything crowd. Many Viet Nam vets were bitter about the treatment they received from an indifferent populace and an angry Rent A Crowd. Many still are.’ (Digger History)

‘The Welcome Home March, 3 October 1987: Because many men returned from Viet Nam in small groups it was not possible to have grand parades for them. When Battalions returned they usually marched through the streets of a major city but these often attracted the rabid rat bag element of the Anti War, Anti Conscription, Anti Government and Anti Anything crowd. Many Viet Nam vets were bitter about the treatment they received from an indifferent populace and an angry Rent A Crowd. Many still are.’ (Digger History)

Minister Ronaldson’s remarks echo plenty of similar claims from Australian politicians over the years. In 1988, Prime Minister Hawke, having the previous year inaugurated ‘Vietnam Veterans’ Day’ (18 August, the anniversary of the Battle of Long Tan) and attended a ‘Welcome Home Parade’ in Sydney, referred to ‘the recognition at last extended to our Vietnam veterans’. Twenty-five thousand veterans marched and at least 60 ooo people lined the streets.*) In 2006, Prime Minister Howard mentioned ‘our nation’s collective failure at the time to adequately honour the service of those who went to Vietnam. The sad fact is that those who served in Vietnam were not welcomed back as they should have been.’ Earlier this year, Prime Minister Abbott, speaking at a welcome home parade for soldiers returning from Afghanistan, said: ‘Now, some decades ago, Australians returned home from another war and were not properly acknowledged’.

A Vietnam War memorial was unveiled in Canberra in 1992 and another parade was held. (The Appendices to this Factsheet contain some archival material on the memorial.) These parades, twenty years on, and the memorial were explicitly seen at the time as making up for what was seen to have been missing earlier. The alleged lack of welcome parades or other conspicuous acknowledgement while the war was under way was regarded as particularly important but other causes of resentment among returned men were what they recalled as mass anti-war feeling directed at them, physical attacks on soldiers, ostracism by the RSL, and lack of empathy and assistance from government departments.

Two books, Michael Caulfield’s The Vietnam Years (2007) and Mark Dapin’s The Nashos’ War (2014), address these claims. Caulfield and Dapin both spoke to dozens of veterans and pored through media of the time. The two books have different perspectives and subject matter: Caulfield looks at the 60 000 personnel who went to Vietnam, Dapin the more than 15 000 national servicemen who went. The following paragraphs quote and paraphrase from these books. Both books also address many other aspects of the Vietnam commitment and are recommended.

A third book, also recommended, is Peter Edwards’ Australia and the Vietnam War (2014), which is essentially a summary of the multi-volume official history of the war, written by one of the official historians. In this highlights reel we have worked in some material from Edwards as reinforcement (or sometimes counterpoint) to Caulfield and Dapin.

General

Edwards gives a succinct summary of the points of contention in how we deal with Vietnam decades on:

A major legacy of the Vietnam War, still highly sensitive, concerns the impact on those who served, and by extension on their friends and families. This is a complex story, in which at least three major strands can be discerned: the reception given to the veterans by government agencies, such as the army, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (as the former Department of Repatriation had been renamed) and the Repatriation Commission, by ex-service organisations, and by the wider Australian community; the impacts, both direct and indirect, of post-traumatic stress on the post-war health of veterans; and the impact of a number of herbicides and other toxic chemicals, generally known collectively as Agent Orange. (Edwards Kindle locations 4559-64)

It is around these intertwining strands that nuances need to be found; welcoming home has many aspects.

‘And the mythology about the war is even more intense. Soldiers returning from Vietnam were attacked by organised anti-war protesters who spat at them, threw blood on them and called them “baby-killers”. No, they weren’t. Vietnam veterans are social misfits, loners, prone to alcoholism and violence. No, they’re not. Australians did not support the war. Yes we did, by a large majority until the last couple of years [of the war]. Australian soldiers were never welcomed home. Yes, they were. And on and on. The gap between veterans’ memories and popular belief about what Australia did in Vietnam, why we did it and even whether we succeeded, remains deep and wide and leaves most people either ignorant or confused. Even now, 40 years later, those two Vietnam Wars have never really come to terms with each other, never really been at peace.’ (Caulfield page xii)

‘”They were treated like pariahs when they came home, weren’t they?” [said Dapin’s friend]. Well, some of them were by some people in some places at some times, but to allow that to become the entire story of 15 381 men [national servicemen] who fought in a foreign war is naive, almost obscene.’ (Dapin Kindle locations 6169-71)

Private Graham Edwards, 7RAR, who later lost both legs in Vietnam, before becoming an MP and advocate for veterans (Australian War Memorial P04724.001)

Private Graham Edwards, 7RAR, who later lost both legs in Vietnam, before becoming an MP and advocate for veterans (Australian War Memorial P04724.001)

Public feeling and parades

‘All but one infantry battalion had a homecoming parade and the welcome was, in the main, riotously enthusiastic.’ (Dapin 882-83) Nine battalions had a total of 16 tours; Edwards (4585) confirms 15 out of 16 tours ended in welcome home parades, ‘the last being as welcoming as the first’. There were also multiple tours by the Special Air Service Regiment, artillery, engineers, intelligence, signallers, and others, plus Navy, RAAF, nursing and other personnel. Order of Battle.

‘One of the most enduring myths about Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War holds that the returned men didn’t receive a homecoming parade until 1987; another is that their welcome home marches were regularly disrupted by protesters.’ (Dapin 2556-58)

‘There were never any organised, formal protests against soldiers in Australia. On the contrary, welcome home parades were held for a number of battalions throughout the duration of Australia’s presence in Vietnam. The parades attracted large, affectionate crowds and only an occasional, often lone, dissenter.’ (Caulfield 403)

Three examples of parades are described below. One of the points that Dapin, in particular, makes is that the media were generally enthusiastic about the Vietnam commitment until the war began to turn. So parades were well reported.

1RAR welcome parade, Sydney, June 1966

Dapin 1490-95, based on Australian and Sydney Morning Herald, 9 June 1966, records that there was a crowd estimated at 300 000 people, telephone books torn into confetti, ticker tape in Martin Place, an elderly woman kissing soldiers in the ranks and young girls throwing streamers. The New South Wales premier had asked employers to give their staff time off to watch the march. An elderly gentleman beat a protester with a walking stick, a woman with an umbrella attacked two other protesters and another protester was knocked over by a policeman. Barristers and builders’ labourers alike applauded.

There was also Nadine Jensen, coated in red paint, a lone woman who burst through the ranks of soldiers. See below, ‘Misremembering’.

‘A half a million people went to the trouble of attending that day. They came to welcome home Australian soldiers from a war in Vietnam; to honour their service to their country. In 1966, four years into our involvement in the war. But no one remembers that. They remember Nadine.’ (Caulfield 359)

4RAR welcome parade, Brisbane, May 1969

‘On 30 May, 4RAR, who had been in Vietnam since June 1968, came home to Brisbane to what the Courier-Mail described as “a most spectacular ‘ticker tape’ reception … Offices and shops emptied and work virtually came to a standstill” … Although there were no demonstrators reported at the parade – nor at any parade in Queensland ever – the paper claimed, inscrutably, “Protest leaders decided not to proceed with any demonstration because Brisbane gave the troops one of the warmest welcomes since World War II”.’ (Dapin 4710-16, based on Courier-Mail, 31 May 1969)

8RAR welcome parade, Brisbane, November 1970

‘Two months after the second moratorium, in November 1970, 8RAR returned to Australia, the first battalion to be withdrawn from Vietnam without being replaced. They marched through the streets of Brisbane and tens of thousands of people welcomed them home with ticker tape and applause. There were no protesters.’ (Caulfield 398)

Moratorium, Melbourne, May 1970 (Australian War Memorial P00671.009/R. Gilchrist)

Moratorium, Melbourne, May 1970 (Australian War Memorial P00671.009/R. Gilchrist)

Attacks on soldiers

‘There were very few protests against returning soldiers, and none of them seem to have taken place at airports. Soldiers were more likely to assault demonstrators than the other way around.’ (Dapin 883-84)

As the war went sour, protesters became more vocal but returning soldiers were still supported by the majority. Soldiers’ memories do not match reports at the time. An official Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) publication in 1990 quoted ‘Mike’ recalling being pelted with tomatoes and spat on by demonstrators at Sydney Airport in 1970. A mass fight allegedly followed, involving hundreds of men. Yet the press at the time reports no such event. (Dapin 4930-40)

Misremembering

Single incidents were exaggerated and this became more common after the war had been lost and with the passage of time.

‘Yet today, the three hundred thousand welcoming citizens [at the June 1966 Sydney parade] have disappeared from memory … to be replaced by flights of swooping, vampiric Nadine Jensens, soaked in plasma. Throughout the Vietnam War, there was no other reported example of returned soldiers in Australia being doused in red paint, blood, entrails or anything else. There were no reported incidents at all of national servicemen being treated this way. All these stories came later, after the fall of Saigon [in 1975].’ (Dapin 1516-20)

‘Every Vietnam veteran I have talked with remembers the woman and the red paint [at the June 1966 Sydney parade], the perceived insult to their uniform, to their service. But not one of them spoke of the half a million people, or the enthusiasm of the reception. One single action, one potent photograph has become the accepted truth … Most Australians still supported our involvement in the war, as well as conscription; in fact three out of every five people said they did.’ (Caulfield 359-60; see also Edwards 2684)

Misremembering also came about because, for various reasons, not every returning serviceman took part in a parade.

‘Men who had arrived in Vietnam as reinforcements were often transferred to other units, where they stayed after their mates went home, until their year in country was over. They might return instead on the evening flights back to Sydney, which some came to believe were smuggling them home like thieves in the night, to hide them from demonstrators who were, in truth, probably never expected. The wounded and the sick might precede their units. Other men might disembark the Sydney before the ship reached the battalion’s home state. Although the men were welcomed home, there was no fanfare after the parade.’ (Dapin 2556-66; also 4950-65; also Edwards 4584-89)

6RAR welcome parade, Brisbane, June 1967, with 60 000 spectators (Australian War Memorial P06136.013/Bruce Minell)

6RAR welcome parade, Brisbane, June 1967, with 60 000 spectators (Australian War Memorial P06136.013/Bruce Minell)

There was one battalion that missed out altogether on a parade.

‘Coincidentally, the men of 6RAR/NZ, whose tour ended in May [1970], were unable to come home on the HMAS Sydney as the ship was in the docks for a refit. Instead, they flew back to Australia, company by company, over several weeks. There was no welcome-home parade for these soldiers, and to some it must have seemed that the moratorium [8-9 May, with an estimated 200 000 involved] was their real public reception, the spit in the face so often cited, perhaps emblematically, as evidence of the way they felt they were treated.’ (Dapin 5090-93)

Edwards summarises the repatriation problems affecting some veterans: re-entry into civil society; rehabilitation from physical and mental elements; hostility or indifference from the community, the RSL, even family and friends; lack of understanding and support from government authorities, including DVA; resentment that non-veterans were relatively unaffected by the war; resentment at lack of parades. (Edwards 4568-83)

Many of these stories may have been exaggerated or imported from American experience, but there had clearly been some serious failures in the repatriation procedures, caused as much by what was not done as by what was done. (Edwards 4583-84; also 4593 ff.)

There are no reported instances of protesters turning up at service funerals to wave placards (despite a single allegation to this effect), the idea that servicemen were ordered to wear civilian clothes (to avoid being harassed by protesters) is an urban myth, and the peace movement was neither omnipresent nor dominant. (Dapin 6190-6200)

Nevertheless, as Edwards observes:

The absence of positive support or comprehension of the difficulties of reintegration into a totally different environment created a vacuum in which stories of hostile incidents could multiply and the sense of abandonment and disorientation could fester. (Edwards 4591-92)

‘Which memory, which version you believe in, depends on who you were and what you saw.’ (Caulfield xii)

The attitude of the RSL

Former soldiers always compare wars and some Vietnam veterans felt discriminated against.

‘I went down to Melbourne and my father took me to his Returned Services Club and I’d been asked to tell them about my experiences and I did that and the old diggers said that wasn’t a war, that I didn’t know what a war was. I was just devastated. I never joined the RSL after that. I came away and just couldn’t cope with it. It was bad enough with the civilians but to have the old diggers say that, it was terrible.’ BILL HINDSON, 1RAR, SAS (Caulfield 443-44)

‘Sadly, it was an insult mostly delivered by World War II men, members of RSLs; and they were often returned soldiers who had not seen combat themselves. Whether every individual who returned from Vietnam encountered this, or the abuse, or the rejections, or the spitting, or any of the long list of offences finally didn’t matter. They all believed they did. For to do it to some was to do it to all.’ (Caulfield 458-59)

‘RSLs wouldn’t have anything to do with us, you couldn’t join RSLs, they didn’t like us, they didn’t want us. People didn’t want, you didn’t dare tell anybody … You kept it quiet, your medals, you threw in the bottom drawer under all your underwear, you never pulled them out again.’ BRIAN WOODS (Caulfield 459)

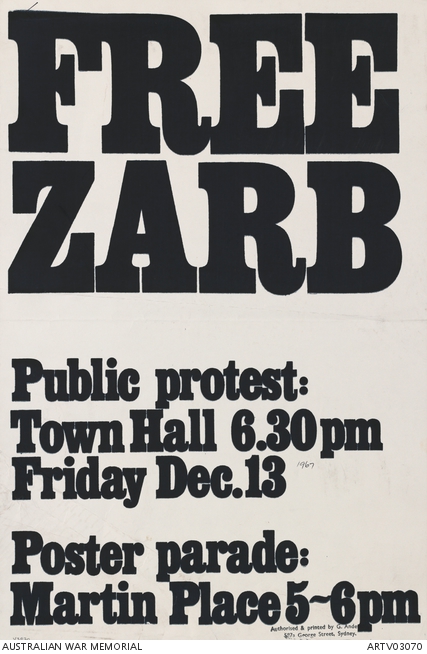

Protest on behalf of conscientious objector John Zarb, December 1968 (Australian War Memorial ARTV03070)

Protest on behalf of conscientious objector John Zarb, December 1968 (Australian War Memorial ARTV03070)

Discontented Vietnam veterans set up the Vietnam Veterans Association of Australia, originally the Vietnam Veterans Action Association formed in 1979, partly because they didn’t trust or respect the RSL. The Association’s motto today is ‘Honour the dead but fight like hell for the living’. Yet veterans’ calls for special treatment and a popular feeling that some of them were mentally unstable ‘gave them the unfortunate air of being whingeing victims’. (Caulfield 460; also Edwards 4595-97) ‘Vietnam veterans aren’t victims’, counters the VVAA, ‘they are achievers’.

But the RSL was not beyond redemption.

‘On 25 April 1972, the RSL honoured men returned from Vietnam by inviting them to lead the Anzac Day parade through Sydney. One hundred and fifty thousand people turned up to watch the march, vastly outnumbering the attendance of any demonstration against the war anywhere in Australia ever.’ (Dapin 6041-45)

Bearing the burden

‘There is always the danger that, in looking back, one can be overcome by sentiment, by regret, perhaps even take guilty pleasure in melancholy. But until we know how we came to be the way we are now – until we can, with clear eyes, understand what we lost along the way, we cannot possibly look forwards. The men and women who served in Vietnam, those Australians who were made to feel personally and morally responsible for a war their country banished, deserve no less.’ (Caulfield xii-xiii)

Comment by David Stephens

Caulfield and Dapin are not the last word about what happened four decades ago. There has been an official history of Australia’s involvement and many other books and articles have been written. Vietnam veterans’ groups and individuals have websites and stories to tell. Honest History hopes this post will lead to robust comment.

How well DVA and its predecessors have served Vietnam veterans has clearly been an issue over the years. A recent speech by Minister Ronaldson focused on government initiatives in Vietnam veterans’ counselling and the return of bodies, as areas where deficiencies had been or were being redressed. The record regarding the recognition of Agent Orange effects has been seen by many as lamentable. (For a summary of Agent Orange and related issues, see Edwards 4595 ff.)

Caulfield and Dapin provide well-evidenced material, which Edwards reinforces. Their findings need to be set against the remarks of politicians past and present quoted earlier in this piece. When prime ministers and ministers speak they need to focus on specific cases of official and community neglect – what Edwards calls ‘what was not done’ – rather than make generalised remarks which too easily become ‘dog-whistles’, calling up high profile but untypical incidents like Nadine Jensen’s demonstration or the reactions of some RSL members.

It is unclear whether politicians’ remarks over the decades have arisen from ignorance or from accepting myths or, on the other hand, whether claims about failures to welcome or acknowledge, or spitting, or harassment by protesters, are a way of diverting attention from government and bureaucratic failures. Generalised remarks cater to misremembering of the type described by Caulfield and Dapin.

Such remarks have political implications as well. Politicians are adept at turning commemoration of past wars into support for current ones. In similar fashion, remarks hinting at past disunity and disloyalty can be a means of seeking unquestioning support for current or future military ventures.

Like all war stories the Vietnam one is complex – more complex than is implied by the fact that the date of a single and untypical battle, Long Tan, has been designated as the date for the major commemorative service for the complete war. ‘Mythbusting’ in relation to Vietnam is not about knocking off one partial or misleading story and substituting another; it is about trying to get right with many elements of a troubled time. Close examination of the history of Australia in Vietnam should, at the very least, encourage politicians towards a more nuanced and honest presentation of this part of Australian history. We can but hope.

Update 10 June 2015: a remiscence from a Tasmanian veteran.

* Dapin 2558 and Edwards 4655 say the crowd was 60 000. The official page says ‘several hundred thousand people’.

David Stephens registered as a conscientious objector against the Vietnam War, one of the 1200 who did so. When his number was drawn out, and not being entitled to further educational deferment, he became a National Service Act defaulter. He took part in the first moratorium in May 1970.

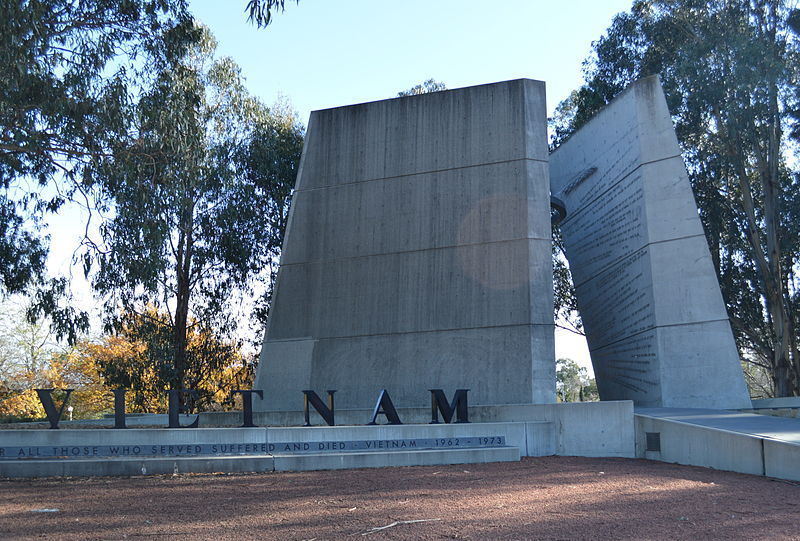

Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial, Canberra (Wikimedia Commons/Mattinbgn)

Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial, Canberra (Wikimedia Commons/Mattinbgn)

Appendices: archival material and comments on the Vietnam Memorial, Anzac Parade, Canberra

This material was originally prepared in 2012 by David Stephens for the Lake War Memorials Forum, which campaigned successfully against the building in Canberra of new World War I and II memorials, to rival the Australian War Memorial.

Appendix 1: The Vietnam memorial: recognition of service in response to the demands of veterans

Key findings from a scan of NCA [National Capital Authority] files and contextual material are:

In 1988, the then Minister for Veterans’ Affairs, Ben Humphreys, responding to the report of the Royal Commission on the use and effects of chemical agents on Australian personnel in Vietnam, said that the Government would be prepared to put money towards a memorial, following appropriate CNMC [Canberra National Memorials Committee, the decision-maker] consideration. But the terms were clear:

The Australian War Memorial has been established as the national monument to the veterans of all the wars in which Australia has been engaged. An important aspect of this monument is the commemoration of veterans fallen in all wars, including the Vietnam conflict, by inscription of their names on the cloistral walls of the memorial.[1]

The Vietnam memorial would be built as a response to the demands of Vietnam veterans for recognition of their service but the Australian War Memorial would retain its role of commemorating sacrifice. This policy firmed up over subsequent years, as the NCA material shows, despite some lack of clarity from time to time.

The policy reflected the views of at least some Vietnam veterans. At a meeting early in 1989 between the CNMC [Canberra National Memorials Committee] secretariat and representatives of the Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial Committee (AVFNMC), AVFNMC representative Peter Poulton was recorded as saying, ‘The wall concept as was used in the USA has been rejected. Some people do not want names put up’.[2]

The CNMC and relevant officials worked through the issue in 1990-92. CNMC member Dr John Hewson, Leader of the Opposition, after consulting colleagues, including Tim Fischer, a Vietnam veteran, had asked Arts and Territories Minister David Simmons to

confirm that the Memorial will not include individual names of veterans who died in action. I understand this is the custom in relation to the various memorials in Canberra to sections of the Armed Forces. The comprehensive list of names of those killed in action is recorded at the Shrine of Remembrance [sic] within the Australian War Memorial.[3]

Minister Simmons replied on 26 September 1990, confirming that ‘the Memorial will not include the individual names of veterans who died in action’.[4]

A meeting of officials and the AVFNMC in April 1991 rejected a proposal from the memorial’s designers that the full list of names, high up in the memorial, could be constructed so as to be read with binoculars.

The meeting considered that there could be some difficulty with this idea. Assurances had been given to a number of people [presumably including Dr Hewson] that the names would not be visible but would be contained in a sealed capsule. It was not felt that this could now be changed.[5]

Officials in DASETT still sought clarification, taking advice from Dr Alan Roberts, an authority on national memorials in Canberra, but the further assurances given to the CNMC that names would not be shown had settled the matter and the CNMC approved the memorial design on that basis.[6]

The Chief Executive of the NCPA wrote to Mr Poulton of the AVFNMC on 15 May 1992 concerning a proposal from some Vietnam veterans that the names should, after all, be included. (This was less than six months before the proposed date for dedicating the memorial.) The Chief Executive said this was a significant departure from previous views of the AVFNMC and ‘an issue of major concern’ to the NCPA. ‘A specific condition of this brief [for the memorial] was that the names of the fallen would not be displayed on the Memorial but “be entombed within the Memorial”.’ (There are copies of the brief on the files. The wording is accurate.) Any change would have to go back to the CNMC and, given the concerns previously expressed there (particularly by Dr Hewson, see above),

there is little to indicate that their response would be favourable. It is anticipated also that the Committee would be particularly concerned also, to address the implications for other National Memorials: the names of the fallen are listed in the Shrine of Remembrance [sic, just as in the letter from Dr Hewson above] in the Australian War Memorial, a short walk away at the head of Anzac Parade, and this is consistent with all other memorials in Anzac Parade.[7]

The apparent change of mind from the AVFNMC had no effect. By 1999, with the Vietnam memorial built, the policy was settled, in words very similar to those of Minister Humphreys a decade before.

No memorials on ANZAC Parade include the names of individual casualties. All Australians killed in war are commemorated in the cloistered wall of the Australian War Memorial. The Committee [the AVFNMC] did not wish to duplicate the functions of the Australian War Memorial.[8]

Appendix 2: Why Vietnam was different

In November 1988, a DASETT official, Robert Deane, chaired a meeting of officials supporting the CNMC. His opening remark about the proposed Vietnam memorial was as follows: ‘This is a different Memorial to all the others’.[9] Why was it different?

There is something of an answer in the final report of the panel which chose the winning design for the memorial. It is notable that these considered words include no reference to ‘sacrifice’ or to the number of service people killed in the war and only a generalised reference to death in wars in general. The importance of the memorial to veterans, those closest to the deaths in the war, is stated as secondary to its importance to future generations. The rationale for the memorial is as much cultural and sociological as commemorative.

The selected design will achieve two purposes:

- be meaningful to Vietnam Veterans, which includes a degree of currency, to remind them of what the war was about; and

- more importantly, provide future generations with recognisable pictures, imagery and information enabling them to understand and see something of that war and especially its differences to other conflicts.

Suffering, death, tension, fatigue and mateship are common to all wars. Vietnam Veterans can not and have never claimed any monopoly over these long-standing common emotions and feelings, all so amply reflected in the many sculptures and iconography in the Australian War Memorial nearby.

What therefore were the differences that singled out this conflict to the extent that the Government has deemed it appropriate to allocate a rarely given site in Anzac Parade? It is suggested that the differences included:

- it was our first electronic media war when what was done on the morning battlefield was shown in the evening lounge room TV. Because of this, the war and actions of individual soldiers were immediately judged as no previous war was ever judged;

- it was our longest war;

- while it directly affected only 50,000 service personnel and their relatives and friends, it evoked a high degree of political and social debate and dissension;

- the mix of National Servicemen and Regular Army soldiers involved and the controversial conscription issue;

- the equipment used was unique, especially the helicopter, which, above all else, became symbolic of the war.[10]

[1] House Hansard, 19 May 1988, p. 2676, accessible at https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au .

[2] Summary record, CNMC officials meeting with AVFNMC representatives, 2 February 1989, Department of Arts, Sport, Environment, Tourism and Territories (DASETT) file 89/2890/f.216, CNMC – National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces.

[3] J. Hewson to D. Simmons, 14 September 1990, DASETT file 90/6706/f.51, National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces.

[4] D. Simmons to J. Hewson, 26 September 1990, DASETT file 90/6706/f.57, National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces.

[5] Summary record, CNMC officials and AVFNMC representatives, 8 April 1991, DASETT file 90/6706/f.113, National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces.

[6] J. Hunt, National Functions Section, DASETT, to Director, National Functions, 15 May 1992, DASETT file 90/6706/ff.189-90, National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces.

[7] L. Neilson to P. Poulton, 15 May 1992, NCA file 90/135-05/n.f., National Capital Enhancing Activity Australian Vietnam Forces Memorial Design.

[8] Minister McDonald to Bruce Billson MP, 1 April 1999, NCA file 98/352/f.94, Australian Vietnam Memorial.

[9] Summary record, CNMC officials meeting, 28 November 1988, DASETT file 89/2980/f.187, National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces.

[10] L. Neilson, Chief Executive, NCPA, to D. McIntyre, Secretary, CNMC, DASETT, 23 July 1990, DASETT file 90/6706/ff.30-31, National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces.

https://independentaustralia.net/australia/australia-display/reflections-on-the-fall,4404