John Moses*

‘The contingency factor in national historiography: Germany and Australia’, Honest History, 25 February 2018

ABSTRACT

This paper observes that what historians choose to write about is determined by the circumstances of their time and place. The paper does not attempt to canvas the personal characteristics required to be able to write history. It just focuses on obvious examples to illustrate how and why history is written. It will be seen that history is always conditioned by the circumstances in which the historian as political pedagogue finds herself. This writer draws here on his experience as an Australian abroad in Germany at a specific time, 1961-65, and his continued involvement in the historiography of that country. Being an ‘old’ Australian, he also has some observations to make about Australian national historians. All this, of course, severely modifies Leopold von Ranke’s famous advice or motto: ‘I only want to show how it essentially was’ (Ich will nur zeigen, wie es eigentlich gewesen). The inherent subjectivity of being a historian at all rules out the possibility of ever attaining clinical objectivity, whatever that might be.

‘No historian writes without some axe to grind or some cause to promote.’

I: Germany

What the historian chooses to research and write about is largely determined fortuitously; that is to say, it is influenced by situations perceived in the historians’ mental environment which trigger the curiosity and the desire for a rational explanation. In particular, political crises which often result in conflict will inevitably inspire the historian to trace the historical roots to establish a chain of causality.

Goetheplatz, Frankfurt, 1961 (Stadtseitenblog)

Goetheplatz, Frankfurt, 1961 (Stadtseitenblog)

Therein lies the essential justification for historical writing. Historians are scholars who perform an essential cultural-pedagogic task in all open and civilised societies. Without a recorded memory a society remains anchored in a pre-literate tribal state. But even here we need to take a step back and observe that what we deign to call ‘primitive societies’ actually do cultivate an awareness of the tribal past, an awareness which gives them their collective identity. One only has to think of our ancient Aboriginal fellow countrymen whose identity is determined by their recollection of past ‘events’, be they metaphysical or actual.

All peoples, so it would seem, perceive the need to understand their environment, at least in some degree. Indeed, one could argue with justification that a good citizen in our time has to be one who comprehends at the least the origins of the nation’s political system. For example, one is compelled in a democracy, say, at election times, to reflect on the historical roots of the constitution, the legal system and the origins of the political parties.

The questions about basic rights and the constitutional obligations of citizenship, are, of course, taken for granted by most, but obviously a fair minority does reflect on these matters, judging by the range of publications that are on offer in our better bookshops. Topics ranging from the biographies of distinguished citizens from all walks of life, political histories, exploration studies, religious and ecclesiastical histories, military history and international relations, in short, everything that has had some significance on the life of the community and the nation is on offer. Obviously, publishers think that what they choose to lay before the public will be found both edifying, culturally significant and therefore worth buying by the literate population. Indeed, the contents of bookshops are a yardstick of the cultural sophistication of the community. The kind of books people read is a guide to communal sensitivity.

One does well to remember that the proof of an ‘open society’ is the freedom of expression and the freedom of the press. This is never the case in dictatorships, where censorship of ideas is demanded by the ruling elite or warlord as essential in order to sustain the required submission to the party ideology. Such societies have institutionalised government censorship committees whose task it is to monitor what the public get to read.

Aeroflot, 1960s (Saatchigallery)

Aeroflot, 1960s (Saatchigallery)

I know this from personal experience. Once many years ago, during the latter part of the Cold War, I ventured to fly to Germany on study leave by booking an Aeroflot flight to Moscow, where I spent two interesting days sightseeing with a small group of Swedes. The further flight to Frankfurt was booked on Lufthansa, and as luck would have it my companion on that flight was a Soviet citizen from Azerbaijan. He noticed me reading the German magazine Der Spiegel and asked in German why I was going to Frankfurt. He was clearly a very garrulous person so I explained who I was and why I was also flying to Germany. He was going to a scientific conference there, so I realised immediately that he must have been a reliable member of the Communist Party. He belonged to the Reisekader meaning those Soviet and Eastern bloc citizens who were trusted by their respective regimes to make visits to foreign counties and come back.

But this man wanted to use the few hours it took for us to fly from Moscow to Frankfurt to improve his English. He explained that he regularly listened with his family to the BBC English language courses, which recommended certain English authors as good examples of colloquial English. The government censorship was very strict on allowing potentially politically subversive foreign material into the country. Therefore, the literature he wanted to read had to be totally apolitical.

Then came the big ‘bite’: would I be able to procure for him a selection of paperback novels by a BBC-recommended author whose work fell into the apolitical category? I had already explained that I would be going to England after my German research trip. My Soviet companion then said that if I went to a good book shop, the novels of this author would certainly be available. And so they were. I duly ordered and paid for them to be sent to the man’s address in Azerbaijan.

Months later after my return to Brisbane a card arrived confirming with gratitude the arrival of the books. I felt I had done at least something to improve Australian-Soviet relations. Incidentally, he said to me that we Australians would soon be having our own uprising of the proletariat to herald the socialist revolution. My reply was that, from my reading of Australian history, that was very unlikely. But the fact that he mentioned it at all was significant because it meant he was demonstrating his indoctrination in Marxist-Leninist ideology even if he did not really believe it.

Novels will, of course, outsell straight formal history as a rule, since the wider public’s thirst for entertainment is unquenchable. But history still retains a respectable following in all civilised countries. Citizens are both curious about the national past and also usually quite patriotic. And they are, as well, bound to be selective about what they prioritise in their comprehension of national history. Perhaps only a few can get behind the agenda of the individual national historian and figure out what s/he is trying to do with the material.

University of Queensland, 1960s (Queenslandplaces)

University of Queensland, 1960s (Queenslandplaces)

I well remember again an inspiring teacher I had at the University of Queensland. He had written arguably the very first comprehensive history of Australian literature. His name was Cecil Hadgraft and he was a Reader in the Department of English. Of course, I am trying recall lectures he gave over 60 years ago, but the one of his I remember most accurately dealt with how we should criticise a piece of writing, be it poetry or prose.

Hadcraft said you had to examine these four things: sense, tone, feeling and intention. So what is that all about? The sense was the plain meaning; tone meant the attitude of the author to her readers; feeling indicated the attitude of the author to her subject; intention meant what the author was trying to persuade the reader to believe – as well as to inform the reader about. I have always found this to be a most useful analytical tool in trying to assess the value of any piece of writing, but most of all historical writing.

While I was a student in Germany during the mid-60s the historians were in turmoil trying to explain the rise and fall of the Third Reich. It was as though they were all shell-shocked by the horror of what had happened. At that time, cities like Munich, Nuremberg, Berlin, Hamburg and Cologne were still deeply scarred by the savage Allied bombing raids. As late as 1963, I personally experienced an occasion when an unexploded bomb was being defused in the rubble of bombed-out street blocks in Nuremberg.

After the liberation (as it was called) from National Socialism, the universities, having been de-Nazified, re-opened their doors, often with many completely new staff or with professors who were able to return home from their enforced exile in Britain, America or Sweden. That was the case in both Munich and Erlangen where I spent a good five years from 1961.

The historians, sociologists and theologians all felt obliged to account for what had led to the devastation. And here I can give you examples from my personal experience. In Munich, capital of Bavaria, the American occupation forces had ensured that a totally de-Nazified faculty was installed at the university. As Head of the newly constituted department or seminar for modern history they had appointed a well known Roman Catholic liberal named Franz Schnabel. He was a mild-mannered man who in a subtle way was instructing students and the general public who crowded into his weekly two-hour lectures that the root cause of the war and defeat was the political culture of the absolutist monarchy of Prussia, that is, the Prussia of Frederick the Great which Bismarck had imported into the late 19th century when he founded the Prusso-Germany empire.

Franz Schnabel (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology)

Franz Schnabel (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology)

I attended Schnabel’s lectures and seminars for two years and then migrated north to Erlangen where I experienced something similar from the Reformation historian Walther Peter Fuchs. But, instead of lecturing directly on Luther and Calvin, Fuchs got up close and personal with the leading 19th and 20th century German historians who perceived themselves as the political mentors of the nation. Fuchs had concluded that these historians had all played a fateful role in glorifying an authoritarian political culture by teaching that the unification of Germany under Prussia was a law of history, indeed one willed by almighty God Himself.

These men were all disciples of GWF Hegel, the philosopher of the Machtstaat, or power state, in short, they were advocates of a ruthless Machiavellism. And this had been the seed bed in which the Nazi movement sprouted and took off, with its disastrous consequences.

So, I am making the point that many historians are men of intense patriotic fervour who often write not to show how the past actually was, but how they want the future to become. But, then along comes an outsider such as Franz Schnabel was, or a convert like Walther Peter Fuchs, and, in the light of the radically changed political situation such men revise previous interpretations quite radically.

This situation got even better: nothing was more radical during my time as post-graduate student in Germany than the ‘Fischer controversy’. Professor Fritz Fischer, urged on by his students and tutors, chiefly Dr Imanuel Geiss and others, felt obliged to explain – from his point of view – what had gone wrong. From my frequent research trips to Hamburg and Berlin I came to know Fischer, Geiss and other leading revisionists very well over the years.

When you examine Fischer’s biography you can see encapsulated in it the fate of the honest German educated elite, the so-called Bildungsbürgertum. I say ‘honest’ advisedly, because by no means all were able to jump over their own shadow, that is, accept that their previous training had been so disastrously wrong and then start all over again. Yet this is exactly what Fischer did. He and his students effected an intellectual-spiritual revolution in Germany after 1961. I was a fascinated bystander.

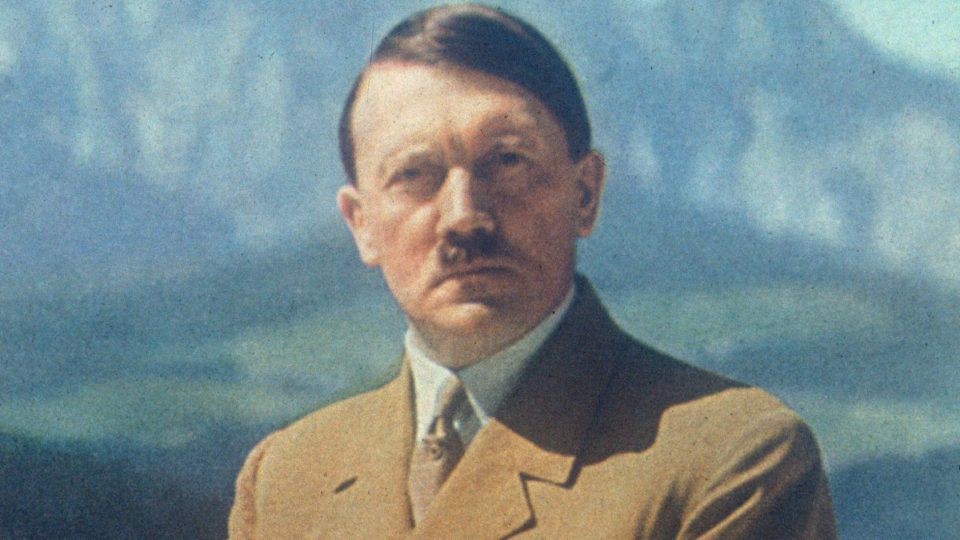

Fischer, born 1908, died 1999, was the son of a Protestant Franconian railway official based in the very Roman Catholic town of Eichstätt. Everything, so Fischer told me, was schwarz, stark katholisch. He was the only Protestant in the Gymnasium, the boys’ grammar school, so he became ever more defiantly Lutheran. And from 1923 to 1926 he belonged to a radical right wing, anti-Semitic fraternity called Bund Oberland, in which he received pre-military training. Later he graduated to a Protestant student fraternity named Uttenruthia which fostered excursions to the German border lands to help out on peasant holdings. The ideology of ‘blood and soil’ nationalism had captured an eager young disciple. So, not surprisingly, as with tens of thousands of other students Fischer in 1933 joined the SA, the Sturmabteilung of Brown Shirts and on 1 May 1937 he became a formal member of the NSDAP (the Nazi Party).

All this took place parallel with an intensive university training in Protestant church history. Fischer was undeniably an enthusiastic Protestant Nazi who had come to regard Hitler as the Saviour for God’s new chosen people. We have to comprehend Nazism as a virulent form of religious belief.

With the advent of war, Fischer found himself allocated to the army education department section, where he taught soldiers such subjects as the ‘The Penetration of Judaism into the culture and politics of Germany over the past 200 years’, followed by ‘The Penetration of Jewish blood into the English upper classes’, as well as ‘The Role of Judaism in the economy and government of the USA’.

Along the way, Fischer had qualified for appointment as a full professor and eventually received a call to a chair at the University of Hamburg. However, fate intervened in the form of the US army’s invasion of southern Germany. Consequently, Fischer spent a considerable time behind barbed wire, and this proved to be the most radical turning point in his career.

When American education officers discovered who Fischer was they engaged him in a dialogue that completely turned him around. From my later association with him and his family I gained the distinct impression that his conversion to Anglo-Saxon liberal values was genuine and not opportunistic. He was released from the POW camp and finally was free to take up his chair in Hamburg in 1947. There he began to make the most dramatic revisions in German historiography. In short, he initiated nothing short of the political re-education of his fellow countrymen. The question to be answered was: what had gone wrong that facilitated the rise of the disastrous warlord Adolf Hitler?

Being by training a Protestant church historian, Fritz Fischer dared to address the first post-war German Historians’ Congress, which was held in 1949 in Munich, and he spoke on the subject Der deutsche Protestantismus und die Politik im 19. Jahrundert, that is, ‘German Protestantism and politics in the 19th century’. The impact on his assembled peers was sensational. Most of them were conservatives who believed that Hitler was the consequence of the Treaty of Versailles unjustly inflicted on an innocent Germany.

So, if anyone was responsible for Hitler it was really the French and British, aided and abetted in Germany by opportunistic Jews, Liberals, Social Democrats and Communists. Fischer was saying that was all nonsense; he endorsed Franz Schnabel’s explanation, namely that the main cause of the Great War was Prusso-German political culture, dominated as it had been by the Lutheran doctrine of the two kingdoms or realms. This had crippled the growth of a critical but loyal opposition in Germany, such as was characteristic of Western European, British and American politics.

This was strong stuff for Fischer’s embarrassed and embittered colleagues. Some of the conservatives never forgave him, but his impact could not be overturned especially as he followed up with hard hitting articles in the Historische Zeitschrift (Historical Journal) and then in 1961 with the massive study of German war aims 1914-18, entitled Griff nach der Weltmacht. Then in 1969 came Krieg der Illusionen which covered the course of Germany policy that led up to the Great War.

The debate among modern historians of all civilised countries that Fischer unleashed has been going on ever since 1964, when Fischer and his students had to defend themselves against the passionate objections of their assembled conservative colleagues at the Berlin Historians’ Congress of that year. The crowds were so big that marquees with loud speakers had to be erected outside the lecture theatre so that all could hear the debate going on inside. I was there. Fischer and his Assistenten defended themselves valiantly and won the support of many of the assembled students. The time was clearly right for a satisfactory explanation of the dark forces that had influenced the course of Prusso-German history.

So Fischer has gone down in the history of historiography as the leading champion of the continuity thesis in German history, that is, continuity between Luther and Hitler. This means that an authoritarian political culture had begun to emerge out of the Reformation era when Luther enunciated in various publications his version of what is the doctrine of the two kingdoms or realms. These are the twin authorities of Church and State. It meant that the King or prince had supreme authority over secular matters, law and order, war and peace, while the Church had supreme authority over spiritual matters. And the two authorities never should interfere with each other.

Luther and Hitler (Wikipedia/The New Daily)

Luther and Hitler (Wikipedia/The New Daily)

The trouble was the King was head of both State and Church as God’s anointed ruler. It was the German version of the ‘divine right of kings’, according to which the King (or his officers and ministers) could command absolute obedience from all subjects. And because the secular authority of the King extended over the Church as well, there was a merging of the two entities: Church and State. By the mid 19th century there were leading theologians in Germany arguing that there was a complete identity between Church and State, that, in fact, the State was essentially the Church acting in the world.

This idea, as you may well imagine, has had a tortuous history in Germany, resulting in what I said earlier about Hitler as supreme head of State being feted as the Saviour in person. The notion was seriously upheld by a very large section of the Lutheran Church, who called themselves die deutschen Christen, that is, the specifically German Christians, as opposed to Roman Catholics and other Lutherans who insisted on the total separation of Church and State. That, of course, did not mean that they would ever oppose the State in its secular policies; they simply objected to Hitler interfering in the internal affairs of the Church. This resulted in what became known as the ‘Church struggle’, of which Dietrich Bonhoeffer was the most famous personality.

So Fritz Fischer had radically reworked the paradigm of Prusso-German history. And, as the situation of the divided Germany after 1945 became more and more fixed, the population of the West became increasingly integrated into the Trans-Atlantic world and that meant the adoption of Western liberal political values. Of course, it could be argued that that had nothing to do with what historians or theologians taught, but was the consequence of the Cold War.

Be that as it may, there is undoubtedly a reciprocal action between political circumstances and the ideas of educated people. The reflections of historians on the nation’s condition, their engagement in a public conversation in which rival explanations complete with each other in the market place of ideas are normal processes in an open society where change and adjustment have to be encountered by all citizens.

II: Australia

The same is true of Australia as well, where we have had our ‘history wars’ in which various self-appointed intellectual leaders have ventured to explain the settlement of Australia as either an invasion or simply the peaceful occupation of a terra nullius. But as John Howard memorably said, we do not need a ‘black armband’ interpretation of the nation’s history. Here I simply want to highlight the national historian’s political-pedagogic role in showing the community how it should understand the emergence of an Australian identity. Space and time permit only a few select examples.

George Arnold Wood (Living Peace Museum)

George Arnold Wood (Living Peace Museum)

From the appointment of George Arnold Wood as the first full-time professor of history at the University of Sydney in 1894 (where he served until his death in 1928), all subsequent professors have engaged in setting a national political-pedagogic agenda. They assumed the role as if it had been part of the job description. And ‘Woody’ being what he was, namely an English Nonconformist, a man with an acute sense of duty and morality became a political pedagogue of a special kind.

Wood’s career at Sydney was a prime example of the ‘political’ professor in one predominant regard and that was to inculcate in his students a ‘Whig’ sense of history. That means one should understand history as an evolutionary process, in which the nation develops towards the goal of democracy and freedom. So George Arnold Wood was a militant Whig. His understanding of English history from Magna Carta in the 13th century to the present was a kind of deterministic struggle of the forces of liberation against those of reaction and conservatism.

Why did Wood believe this? It was because he was brought up a pious, Bible-believing Congregationalist who came from a tradition that understood the Gospel of Christ to be the blue-print for human behaviour.

For Wood, the only good politician was one whose policies intended to liberate human beings from the bondage of slavery and poverty. He opposed with all his being the privileged classes and all forms of exploitation and oppression. It sounds as though ‘Woody’ had been reading Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He could have read them in the original German if he had chosen but instead he derived his political ideas exclusively from the New Testament. And this is what he applied in his lectures in Sydney, in the conviction that, since we in Australia were not hampered in our society by any old established ruling class, nor nobility, nor House of Lords, we had a better chance of realising the ideals which he held so dear. Unfortunately, in order to do justice to Wood’s long and turbulent career in Sydney, we would need a separate lecture.

Moving on now to Wood’s Melbourne counterpart, Ernest Scott, younger than Wood, who was appointed in 1913 and served as foundation professor until 1936 and died three years later. Scott was an Englishman of similar political values to Wood, though he was not an orthodox Nonconformist like Wood, but initially a Theosophist, having married the daughter of Annie Besant, who was very caught up in the suffragette movement.

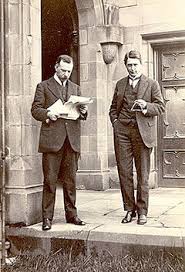

Professors Ernest Scott (left) and William Harrison Moore, University of Melbourne, c. 1914-18 (Wikipedia)

Professors Ernest Scott (left) and William Harrison Moore, University of Melbourne, c. 1914-18 (Wikipedia)

So Scott, too, like Wood was a man of deeply held liberal democratic convictions, and these, too, infused his teaching and research. Even though, later in life, he abandoned theosophy he still maintained his commitment to liberal democratic values and, like Wood, regarded Australia as an ideal place in which these values could be realised. His teaching and research output were all infused with this political-pedagogic example. And both he and Wood had produced a string of gifted students who went on to post-graduate study in Europe and returned to fill chairs around the country.

Names such as Max Crawford, Sir Keith Hancock, Stephen Henry Roberts and Manning Clark spring to mind as the most outstanding examples of this group. They all had stellar careers and were students either of Wood or Scott. All were eminently political and ideologically driven. Let me finish with a glance at Stephen Roberts and Manning Clark.

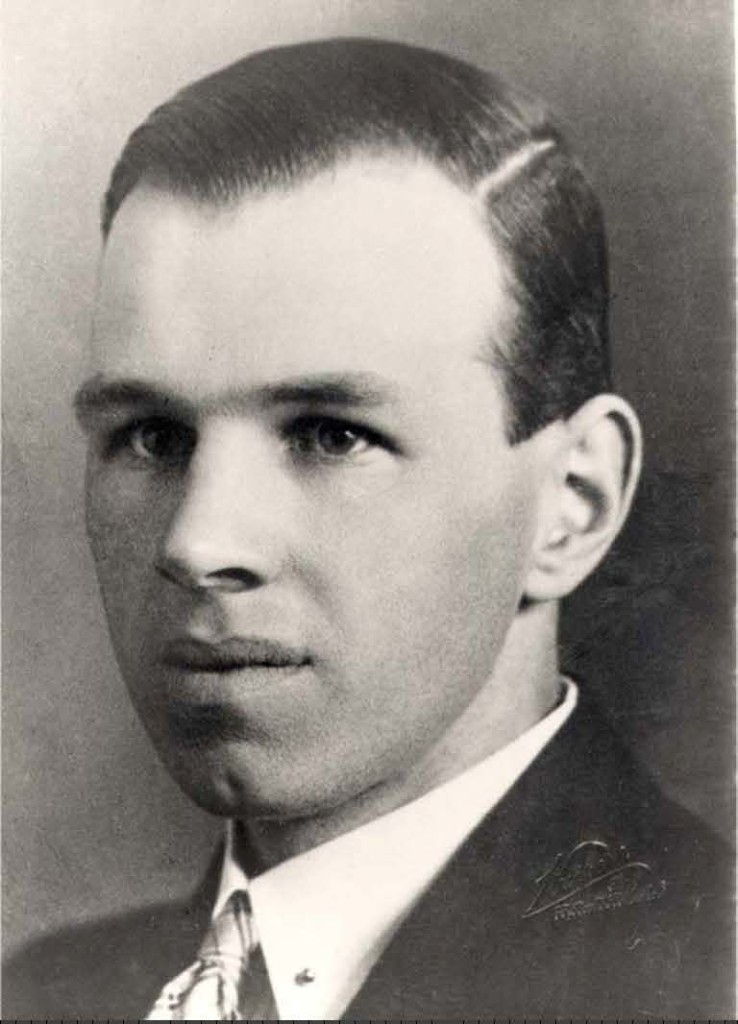

Stephen Roberts succeeded Wood in Sydney, although he had been a Melbourne graduate of Scott’s. His tenure in the Sydney chair lasted from 1929 to 1936, when he became Vice Chancellor. He died in 1971. Roberts was in his bones a ‘political’ professor intensely interested in international politics in the era of the rise of the ‘great dictators’. So political was he that he wrote an anonymous weekly commentary in the Sydney Morning Herald on international relations under the by-line ‘Our European Correspondent’. As well, he wrote articles in English for the German Consul-General’s newsletter, though he also could speak German, his mother being from a German family from Maldon, Victoria.

Roberts’ association with the German Consul-General, Dr Rudolf Asmis, led to an invitation to spend part of his study leave in 1936 in Germany. Asmis had the idea that, if a leading Australian scholar could actually visit Nazi Germany, he would have to come back with a very positive view which he could then propagate from his position as Head of History in Sydney.

As fate would have it, Roberts’ German tour coincided with the famous 1936 Nazi Party Rally in Nuremberg where he took numerous quite unprofessional snapshots, now preserved in the University Archives, all sadly out of focus. He never learned much about photography, but he wrote very perceptively about his impressions of Nazi Germany in what became the best-selling book, The House that Hitler Built.

Stephen Roberts, 1928 (University of Sydney)

Stephen Roberts, 1928 (University of Sydney)

Roberts’ book was the very first extensive scholarly analysis of National Socialism that caused a sensation at the time. In it you can read what Roberts really thought about the Nazi dictatorship. Dr Asmis’ hopes that Roberts would deliver a paean of praise for Hitler’s achievements had been inexplicably dashed. Roberts had been hosted quite lavishly in Germany but he repaid his beneficent hosts with a damning indictment, in which he highlighted the blatant anti-Semitism, oppressive anti-labour and anti-democratic policies of the ‘New’ Germany, and concluded that Germany was gearing up for another war.

Not everybody, including Mr Neville Chamberlain, wanted to believe Roberts. Needless to say the Germans were furious and put Roberts on the long list of persons to be proscribed when Germany conquered the British Empire. So Stephen Henry Roberts owed a great deal of his fame and fortune to his fortuitous association with the German Consul-General in Sydney.

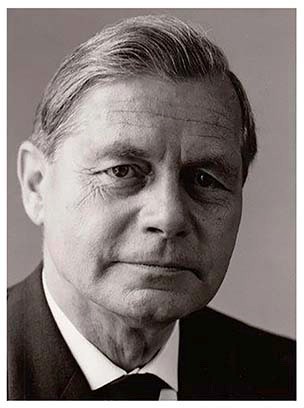

Finally, the example of Manning Clark closer to home. He has gone down in the history of Australian historiography as the leading prophet of Australian national identity. To achieve this he had to emphasise the difference between being a native- born Australian and simply being a transplanted Briton. The Antipodean environment moulded people into a ‘new species being’ to adapt a Marxist phrase. Australians became the ‘young green tree’ distinct from the ‘old dead tree’.

To be genuinely Australian one had to be decidedly anti-British. The contrast had to be emphasised. This, of course, was a curious feature of Clark’s argument, since he had grown up the son of an English-born Anglican priest and was well acquainted with the Book of Common Prayer, in which loyalty to the monarch is central to Anglican identity. By his own account, however, it was Clark’s sojourn at Balliol College, Oxford, that made him deeply hostile to the English, particularly because they did not approve of his batting style. So, being stamped as a kind of colonial upstart clearly rankled with the young Clark.

My own personal encounter with Clark came during his visit to the University of Queensland in August 1979 when he was invited to present the inaugural James Duhig Memorial Lecture entitled ‘The quest for an Australian identity’. This lecture contains all the essential ideas expounded in Clark’s earlier volumes. The main one is his extreme contempt for the British, a fact that certainly resonated with many in the audience, who were of Irish descent.

Manning Clark (suit) as coach of the Geelong Grammar 1st XI, 1941 (Wikipedia)

Manning Clark (suit) as coach of the Geelong Grammar 1st XI, 1941 (Wikipedia)

I spoke next day to Clark only to find that he had absolutely no idea at that time of what we now call ‘ethnic’ Australia. For example, he did not know that the Lord Mayor of Sydney (1973-75) was a person of Lebanese descent named Nicholas Shehadie (who died just recently) and that his successor, Leo Port was a Jew, facts which in themselves attested to Australia’s developing multiculturalism. It is not surprising, of course, that a Melbourne person at that time would never have heard much of Nick Shehadie, who was capped 30 times in the Wallabies Rugby Union team. As an Australian of Lebanese–Scottish descent myself I was not impressed either by Clark’s ignorance of ‘ethnic’ Australia or of his bitterness towards the British.

Much more could be said but perhaps enough has been related to affirm that no historian writes without some axe to grind or some cause to promote. When one picks up a historical work, it is always a case of ‘caveat emptor’. It is the price one has to pay for living in a pluralist society. If there is another way to ensure ‘honest history’, I have yet to hear of it.

* John Moses is a Professorial Associate of St Mark’s National Theological Centre, Charles Sturt University, Canberra. Among many publications, he is co-author with George F. Davis of Anzac Day Origins: Canon DJ Garland and Trans-Tasman Commemoration (2013). He was written a number of articles for Honest History (use our Search engine).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.