‘Money, Monash and motive: the Sir John Monash Centre, Villers-Bretonneux (Immersion I of II)’, Honest History, 7 July 2015

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works (PWC) considered the Sir John Monash Interpretive Centre on 26 June and Honest History attended the public hearing. The Hansard for that hearing is not yet available (we’ll look at it next time – here) but here we analyse the sole submission to the PWC, one from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). (Update 19 August: article on PWC’s report on the project.)

Dedication of the Australian National Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux, 22 July 1938 (Australian War Memorial H17471)

Dedication of the Australian National Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux, 22 July 1938 (Australian War Memorial H17471)

The project

Honest History has been following the progress of the interpretive centre, to be built at Villers-Bretonneux in Northern France. We noted it was a large item in Australia’s overall commemorative spend (a spend which is way ahead of any other country in quantum and per death), we wondered whether it was going to be 50 times better than the Franco-Australian Museum five minutes away, which is being refurbished while the Monash centre is being built, and we observed that loyalty to the interpretive centre concept seemed to be a criterion for membership of Team Australia.

The total cost of the interpretive centre project is estimated at $A99.5 million, comprising $A88.5 million capital costs (to be met by the Department of Defence), $A4.7 million operating costs, and $A6.3 million for staffing, management and operation from 2016-17 to 2018-19. ‘Cost drivers’ were considered in a PWC closed session after the public hearing. This session will presumably have heard about how much of the money goes to French navvies, carpenters and plumbers, how much to Australian architects and wranglers of interpretive presentations, and how much to DVA project managers.

‘The Centre will comprise’, according to the DVA submission, ‘an immersive multimedia journey that provides an evocative, emotional, informative and educational experience for visitors’ (para. 1.8). That’s five polysyllabic adjectives in a single short sentence, which may be some sort of record. The PWC seemed suitably impressed.

The Public Works Committee

The PWC’s role is set out in its legislation. Briefly, the Committee looks at the purpose of the work, its fitness for purpose, the need for it (‘the necessity for, or the advisability of, carrying out the work’), cost-effectiveness, revenue expected (if applicable) and the value of the work. The end point of the PWC process is a resolution of the House of Representatives that it is expedient for the work to proceed.

The PWC process addresses many technical issues. Thus, two-thirds of the DVA submission is about matters like zoning, land acquisition, sustainable design, workplace health and safety, disabled access, car parking, project delivery and risk management. There are some diagrams in the submission but the best impression of how the interpretive centre will look is contained in a You Tube video.

Given the interest maintained by Honest History and others in how Australia is commemorating the Anzac centenary, the PWC analysis of need is of particular concern. Is the PWC able to take account of public opinion, for example? The PWC process is not a broad-based examination of need, independent of the submissions it receives (although it does its own research to formulate appropriate questions). For example, a 2013 PWC report on a somewhat analogous project, the refurbishment of the World War I galleries at the Australian War Memorial, included one page under the heading ‘Need for the works’. The page paraphrased the relevant parts of the Australian War Memorial submission and concluded: ‘The Committee is satisfied that there is a need for the works’.

Villers-Bretonneux, 29 April 1918 (Australian War Memorial E04880)

Villers-Bretonneux, 29 April 1918 (Australian War Memorial E04880)

Where a project has already been announced by government, it is difficult for the PWC to go to fundamental questions, including whether the money could have been better spent on something else (in this case, say, a ‘Western Front Commemorative Fund’ for the dependants of disabled Afghanistan veterans) or whether money from the defence budget should be spent on commemoration and war tourism.

That, of course, raises the question: where can such questions be asked? They are surely the nub of the ‘need’ issue but they are glossed over. The sacred overlay that attends Anzac commemoration even affects institutions like the PWC, founded 1913, which have been around longer than Anzac itself. The Minister’s rant at Senator Gallacher in Senate Estimates (‘Do I take it that the Australian Labor Party does not support the Sir John Monash Centre? Because all I have heard is negativity about it’) is an indication of how easily Anzacker dog-whistling can be used to try to stifle legitimate questioning.

The DVA submission

There is a strong tone throughout the DVA submission of Australia’s contribution on the Western Front needing to be noticed, to be recognised by former allies and visitors generally.

The SJMC proposes to create a physical legacy through:

(a) being an Australian reference point for visitors of all nationalities to the

Western Front;(b) explaining and educating visitors on Australia’s involvement and significant

achievements on the Western Front;(c) enhancing visitors’ understanding of Australia’s role and sacrifice on the

Western Front battlefields; and(d) outlining the impacts of the war on Australia and Australians (para. 1.5; see also paras 1.4, 3.1, 4.3(a), 4.5, 6.4, 18.65).

It will be in the eye of the beholder whether the building of the interpretive centre leads to a judicious redressing of skewed balances in military history or simply gives the impression of crass boastfulness and parochial self-absorption on the part of Australia.

The DVA submission hopes that the new centre will change the pattern of visits to commemorative sites in France. In 2014 there were around 47 000 visitors (para. 9.2) to the Australian National Memorial (ANM) at Villers-Bretonneux (to which the interpretive centre will be adjacent), although there is no nationality breakdown of these visitors available. We understand, however, that most of the 16 000 visitors annually to the Franco-Australian Museum in nearby Villers-Bretonneux are Australian.

Aerial view of interpretive centre (partly buried, to the right) (Architecture and Design)

Aerial view of interpretive centre (partly buried, to the right) (Architecture and Design)

The DVA submission projects that annual visits to the combined ANM-Monash Centre will rise from 47 000 to around 110 000 (para. 9.4). Again, there is no official estimate of how many of the 110 000 will be Australian: one uncorroborated estimate that came to Honest History’s attention claims just ten per cent; the submission clearly expects a good proportion of the total will be British, French and German schoolchildren. (School groups currently make up 36-47 per cent of visitors in the region: para. 9.5.) The message about the Australian contribution in 1918 will be carried home to the lounge rooms of Berlin, Bordeaux and Birmingham by returning bus-loads of teenagers.

The targeting of school groups may also explain the emphasis on immersion. The word ‘immersive’ appears 14 times in the submission; it describes a form of virtual reality. The design of the centre provides for an ‘Immersive Gallery’, which will offer ‘impactful yet informative high level interpretations of the key focus questions’, as well as an ‘Impacts Gallery’. In the immersive gallery, ‘visitors will be able to manipulate large scale 3D virtual objects such as tanks and artillery guns using gesture technology’ (paras 18.72-73). (Rather like pioneer superhero, Mandrake the Magician, who regularly gestured hypnotically.)

It is not clear whether the immersion will extend as far as replicating the effects of such ordnance on human flesh. (If not, why not?) Given that there were at least eight million casualties on the Western Front, an honest portrayal of these four years would be fairly bloody. Even if the centre focuses (as it probably will) only on Australian casualties (180 000, around two per cent of the Western Front total) honest portrayal of this number will be a challenge for the immersive approach, particularly in 3D.

Making sure our ‘significant achievements’ get their due at last may need a more than proportionate supply of ‘leading-edge interactive interpretive technology’ (para. 6.4) to ensure that visitors ‘differentiate the Australian experience from other more universal experiences of the First World War’ (para. 18.65). Perhaps all that 3D and all that ‘gesture technology’ will help show how Australian deaths on the Western Front were different – apart from the fact that they were deaths of Australians.

Those who look at the story of the Western Front from a world history perspective might well argue that the Australian contribution there has received to date pretty much the amount of attention it deserves. Others might welcome some polite but proportionate reinterpretation. The language of the DVA submission suggests, however, that rather more than the latter is in prospect.

Teenagers may be particularly susceptible to the emotional pull of the centre, which is seen as one of its strong attractions.

Content will include first person experiences drawn from letters, diaries, official documents and histories to give a variety of perspectives and to provide visitors with an emotional first-hand connection to century old experiences (para. 18.65).

How long the emotional impact will be prolonged after the return to the air-conditioned tour bus may be questioned. There may, however, be a ‘teachable moment’ in the contrast between the forms of transport available today, compared with a century ago. Or even in the fact that today’s visitors can leave the battlefield when they feel like it.

Finally, the submission indicates another change of direction (besides getting more tourist buses to detour via Villers-Bretonneux). The section headed ‘The need’ commences thus:

The project is a new initiative of the Australian Government with the objective of providing a lasting legacy from the Anzac Centenary that ensures that the service and sacrifice of Australians on the Western Front during the First World War is not forgotten (para. 3.1).

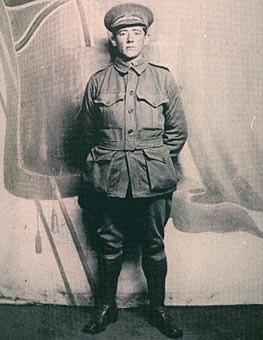

Lyall Howard, father of John, c. 1915 (Daily Telegraph)

Lyall Howard, father of John, c. 1915 (Daily Telegraph)

The remainder of this section is a long quote from Prime Minister Abbott, speaking at Villers-Bretonneux on 26 April this year:

Over the next three years, we will remember the achievement of the Australian light horse in Sinai, at Beersheba and in the capture of Jerusalem and Damascus. But increasingly our attention will turn here, to the Western Front, the main focus of the war, where almost 300,000 Australians fought and 46,000 died.

Gallipoli has dominated our imagination but the Western Front was where Australia’s main war was fought. This is where our thoughts must dwell if we are truly to remember our forebears, pay homage to their sacrifice and honour their achievements.

Gallipoli was a splendid failure; the Western Front was a terrible success and we should recall our victories as much as our defeats … Australians should congregate here, every April 25th, no less than at Anzac Cove.

This is the clearest indication of the motive behind the interpretive centre. The germ of the idea dates back to the days of John Howard (paras 2.1-5). He was the man whose father and grandfather bumped into each other near Mont St Quentin in August 1918. The expensive work at Villers-Bretonneux is symbolic of a new direction in Australian commemoration, away from the scrubby cliffs of Gallipoli and towards the mud and blood of France. It remains to be seen whether sharpening our focus on past ‘victories’ makes us more willing to take a punt on possible future ones.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.