‘Medical women in war’, Honest History, 14 April 2015

Carolyn Holbrook reviews Susan J. Neuhaus and Sharon Mascall-Dare, Not for Glory: a Century of Service by Medical Women to the Australian Army and its Allies

When Dr Agnes Bennett tried to enlist in the First AIF in 1914 she was told to ‘go home and knit’ (Neuhaus & Mascall-Dare, p. 18). Not to be deterred from her impulse to lend her surgical skills to the imperial war effort, Bennett sailed for Britain. When her ship docked in Alexandria en route, Bennett caught sight of wounded soldiers from the Gallipoli campaign, some of whom were Australians. She resolved to stay put. Attached to the New Zealand Medical Army Corps in Egypt, Bennett became the first female military surgeon in the British Empire.

Dr Agnes Bennett, c. 1916-17 (Jennifer Baker, Australian Women Doctors Who Served in WWI)

Dr Agnes Bennett, c. 1916-17 (Jennifer Baker, Australian Women Doctors Who Served in WWI)

After the Dardanelles campaign was aborted in December 1915, Agnes Bennett took charge of a field hospital behind the Greek Macedonian front line, where French and Serbian troops were fighting German-backed Austrians. Bennett’s staff included another Australian surgeon Lilian Cooper, Cooper’s companion Josephine Bedford, who assisted in surgery, several Australian nurses and the author Miles Franklin, who worked as a medical orderly. Perched on the side of Mount Kajmakcalan, 5000 feet above sea level and ten kilometres from the frontline, Bennett and her female colleagues performed amputations, removed shell fragments and bullets and saved hundreds of lives.

Bennett was the last Australian to evacuate the field hospital before it was overrun by Bulgarian bandits who killed all remaining staff and patients. Though the efforts of Agnes Bennett, Lilian Cooper and Josephine Bedford were ignored by their own country, they were recognised by the Serbian government, which awarded each of them the Order of St Sava for humanitarian service.

Why are extraordinary stories like this not better known in Australia? As the authors of Not For Glory, Susan Neuhaus and Sharon Mascall-Dare, point out, the experiences of Australian army nurses are well remembered in books, television and popular culture—think of the Australian War Memorial’s ‘Florence Nurse Bear’—as are those of women on the home front during the world wars. Yet the experiences of women doctors in wartime are little known. The authors’ suggestion that people have assumed that ‘all medical women in the military are employed in nursing roles’ rings true (p. xvi).

Despite Australia’s progressive record of civil rights for women, the Australian Army was slow to accept female doctors. Neuhaus and Mascall-Dare claim that women doctors have had to fight ‘not one, but two wars’: the war against prejudice and the war against the enemy (p. xiv). The Australian Army followed the British lead during the Great War by prohibiting women doctors from enlisting. War was ‘a man’s world’ and women were considered ‘too illogical or hysterical’ to cope with its demands (p. 17). Due to the dearth of medical expertise the British later relaxed their prohibition; the Australians did not.

Dr Agnes Bennett was used to defying the wishes of small-minded men. She had taken out a bank loan and paid her own way to study medicine at the Edinburgh University Medical College. Unable to find work as a surgeon in Britain or Australia, she resorted to work in mental asylums.

Dr Lilian Cooper and Josephine Bedford c. 1900 (Lesbians in 1900 Brisbane)

Dr Lilian Cooper and Josephine Bedford c. 1900 (Lesbians in 1900 Brisbane)

Bennett was not the only female doctor who saw the Great War as an opportunity to put her skills to proper use. Fifteen of the 129 female doctors registered in Australia in 1915 circumvented the Australian and British bans on female doctors to find means of applying their skills to the Allied cause. These women found work in France, Serbia and Malta, working for organisations such as the British War Office, the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) and the Scottish Women’s Hospitals. Neuhaus and Mascall-Dare have examined diaries and other records to tell remarkable stories of endeavour and hardship.

Even when the Australian medical profession at large became more welcoming to women during the inter-war years, the Army maintained its policy of exclusion. Soon after World War II began, it was announced that women doctors would be accepted into the Australian defence forces. The first of these was Dr Winifred MacKenzie, whose commission in the Australian Army Medical Corps was noted in the press. A women’s columnist at the West Australian was pleased to report that Dr MacKenzie’s uniform of khaki shirt, collar and tie, opaque stockings and tan shoes was pleasantly flattering. The columnist assured readers, who might be concerned lest the doctor’s femininity be doubted, that ‘she is a trim figure in her uniform’ (p. 83). At least 26 women served in the Australian Army Medical Corps during the war, mostly in administrative roles.

Since 1990, Australian military personnel have been engaged in peacekeeping missions in places such as Cambodia, Somalia, Bougainville and East Timor, and in combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. Using written sources as well as interviews, the authors tell the stories of individual female doctors and allied health workers.

As well as applying their professional expertise in difficult and highly distressing situations, these women are often dealing with the more prosaic matters of running a family. In October 2002, anaesthetist and army reservist Su Winter was urgently recruited to the Australian medical evacuation team after the Bali terrorist bombings. It was the first time she had left her two-year-old daughter. Her army officer husband was later chastised by his ‘superiors’ for missing a training exercise in order to care for their child.

The later chapters of Not For Glory demonstrate how greatly opportunities have increased for women in the military. In 2013, Brigadier Georgeina Whelan, who led the Australian army’s medical response to the Boxing Day tsunami in 2004, was appointed as the first female Head of Corps of the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps. Navy Rear Admiral Robyn Walker has been Surgeon-General of the Australian Defence Forces since 2011. Walker recently earned the wrath of former soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder when, during an interview on Four Corners in March, she appeared evasive about the role of military service in causing trauma.

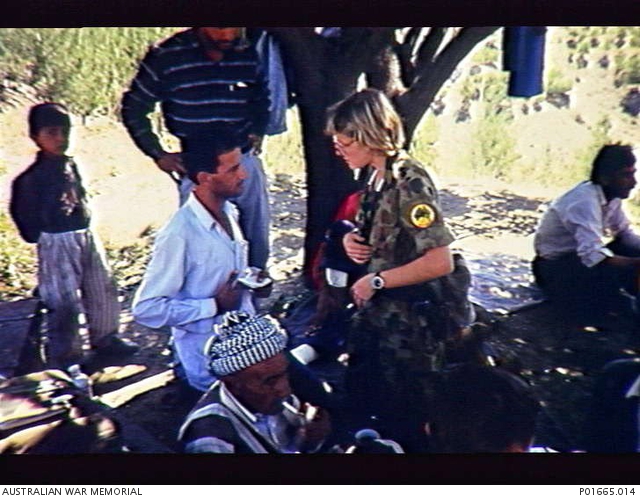

Dr Captain Jane Morris treating refugees, Northern Iraq, 1991 (Australian War Memorial P01665.014)

Dr Captain Jane Morris treating refugees, Northern Iraq, 1991 (Australian War Memorial P01665.014)

By telling the story of women military doctors through the experience of the women themselves, Neuhaus and Mascall-Dare have written a highly readable book. Alongside the stories of remarkable women such as Agnes Bennett, Lilian Cooper, Winifred MacKenzie, Su Winter and Susan Neuhaus herself—a surgeon and retired army colonel—is the story of the increasing recognition of women in the military workplace. However, as we know from the recent stories that have emerged about the behaviour of male cadets at Duntroon and the behaviour of senior specialists in the medical profession, the war against misogyny and sexism is not yet won.

carolyn.holbrook@monash.edu

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.