‘State surveillance in Great War New Zealand’, Honest History , 14 August 2019

John McLeod reviews Jared Davidson’s Dead Letters: Censorship and Subversion in New Zealand 1914-20

Jared Davidson’s Dead Letters reveals the history of postal censorship in New Zealand in the First World War. It does so through letters stopped by the censor and filed away unread for a century. Here is the story of those caught in this fraught web of state censorship – a not unsurprising eclectic collection of German immigrants, political dissidents, pacifists, socialists, unionists, non-conformists, aliens and even an Irish nationalist, all of whom put their heads above the parapet

I came to this book through what may be perceived as two contrary lenses. First, as someone who had a role in shaping and delivering New Zealand’s centenary commemoration of the First World War, but also as the father of two children whose great-great grandfather, while born in New Zealand, was a member of an immigrant family who were victims of anti-German sentiment. Despite that, he and two of his brothers served in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. He was grievously wounded at Messines in 1917 by the same shell that killed his brothers.

I came to this book through what may be perceived as two contrary lenses. First, as someone who had a role in shaping and delivering New Zealand’s centenary commemoration of the First World War, but also as the father of two children whose great-great grandfather, while born in New Zealand, was a member of an immigrant family who were victims of anti-German sentiment. Despite that, he and two of his brothers served in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. He was grievously wounded at Messines in 1917 by the same shell that killed his brothers.

Through both lenses this is an engrossing, although not unsurprising book, one that is integral to our national story of the First World War. State surveillance and the way it so easily crosses the line into political intrusion, targeting activism, nonconformity and dissidence, has long been a challenging issue. And almost invariably as we look back, as in this case, we see this action as grossly unjust or even farcical, an abuse of state powers and something contrary to the principles we were supposedly fighting for.

New Zealand was not alone its approach to state surveillance and censorship and indeed New Zealand and Australian mail censors shared information. Perhaps because it was only overseas mail, and that of the small number of non-conformists who came to the attention of the authorities, there was limited opposition to censorship intruding into New Zealand’s way of life. (Opposition was somewhat more vocal in the Second World War.)

What is so compelling about this book is the way Jared Davidson uses the small number of surviving confiscated letters to weave a story around the writers and the intended receivers of the letters. Fortunately for the tale, among the 500 surviving items in the Army Department’s Secret Registry, there are all the ingredients of a compelling and at times salacious story.

One of these items is about Hjelmar Danneville, a cross-dressing doctor who came to New Zealand in 191, claiming to be Danish. Denounced as a suspicious and dangerous alien, she challenged all the prevailing gender and sexual norms. The authorities were uncertain whether she was a man or woman, as she wore men’s clothing. She was also in an ambiguous relationship with the wife of a local (and unfaithful) vicar, who claimed Danneville had lured her away from him. The Police Commissioner eventually required Danneville to undergo a physical examination to confirm her gender. She became one of the few women to be interned on Somes Island in Wellington Harbour. Eventually, she and the vicar’s wife left New Zealand for a new life in San Francisco.

The story of Marie Weitzel, German-born and in her mid-50s during the war, had particular resonance for me. She wrote to a German relative in 1916 of English ‘wickedness’ and the appalling and unfair way Germans were treated in New Zealand. ‘God will help the Germans’, she wrote. By then, Weitzel had long been the subject of police attention with her own socialist class politics and the prevailing anti-German sentiment. Not for the first time, those in authority in a patriarchal society struggled to deal with a troublesome and feisty woman. Weitzel openly defied the authorities, ignoring movement restrictions and other controls. They vacillated between wanting to intern her and deport her, but in the end could do neither.

Davidson brings a passion and enthusiasm to the way he writes, telling a story closely linked to his own personal values. He – successfully, I think – avoids using too much of a twenty-first century lens in Dead Letters. He does, however, draw out the underlying class and labour conflict themes evident in New Zealand at the time in a way that some might feel overstated. Yet it was this very undercurrent coupled with the disaffection of returned soldiers and their families that led to major social change in New Zealand during the 1930s.

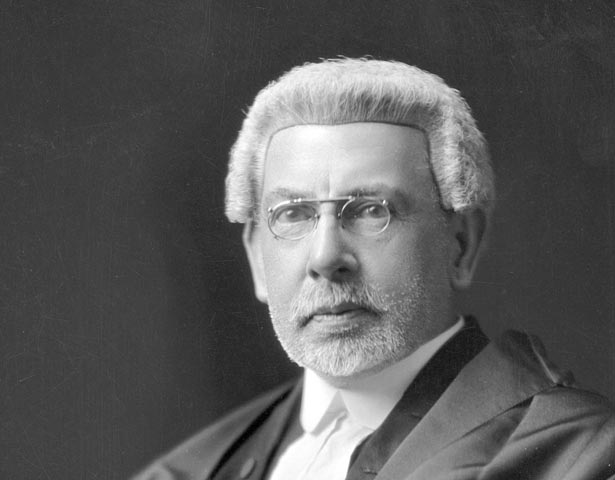

What of those who were responsible for this arbitrary, almost unfettered use of state power – Chief of General Staff and Chief Censor Colonel Charles Gibbon, Deputy Chief Postal Censor Walter Tanner and the Solicitor-General Sir John Salmond? Davidson says they were ‘not bad men’, and he observes that both Salmond and Defence Minister (and often Acting Prime Minister) Sir James Allen shared the personal cost of war, as they both had sons killed.

Davidson somewhat charitably suggests that the combination of lost wartime legislation, coupled with their ideological world view, gave these men considerable power, which they used to oversee this program of censorship. Of course, they were the architects of the wartime legislation, so the argument becomes a bit circular. It is clear, though, they were not operating with the malice and overt ideological bias that has become apparent in some Western democracies in recent years.

Sir John Salmond (NZ History Online)

Sir John Salmond (NZ History Online)

So where was the political oversight? As Davidson notes, Prime Minister WF Massey and Sir James Allen shared the same world view and were complicit in these acts of state surveillance, even on the United States consulate. Public hysteria, as well as anti-German and anti-organised labour sentiment, helped provide the permissive environment for the censorship regime.

New Zealand’s record in managing or even tolerating dissent in the Great War is not something to be proud of. Courage and sacrifice is often seen as synonymous with the battlefield. It, too, was very evident among those who made New Zealand their own conflict arena, whether through principle, being born in the ‘wrong’ country or simply choosing not to be involved in this war.

Dead Letters is an important book, laying bare one of the pillars by which the state controlled subversive elements in the First World War. Ironically, even as posted letters have become dead during this century, the challenge of balancing individual privacy and collective aims has become even starker as the state has acquired a new range of surveillance tools.

* John McLeod is a former Army officer who was the New Zealand Defence Force’s commemorative lead for the First World War centenary as well as a member of the steering group for the New Zealand Government’s WW100 programme. He is the author of the controversial book Myth and Reality: The New Zealand Soldier in World War II and one based on his peacekeeping experiences in Angola. He tweets.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.