‘Australia and the Vietnam War: Part 2 – No-win situation’, Honest History, 20 December 2022

Greg Lockhart is a leading historian of Australia’s Vietnam War (Nation in Arms: the Origins of the People’s Army of Vietnam; The Minefield: an Australian Tragedy in Vietnam). His article (in two parts; Part 1) is published to mark the 50th anniversary of the last Australian Army parade in Vietnam, 16 December 1972, in which the then Captain Lockhart participated, and also serves as a summation of his work on the Vietnam War. HH

Introduction

In Part 1, we saw how from the 1940s to the 1960s conservative Australian governments feared the threat of decolonisation in Asia but could not say so, as Asian nations were becoming independent. At the same time, those governments were able to override that geopolitical contradiction by adopting the anti-communist rhetoric of the Cold War. By overlaying the old ‘yellow peril’ with the rhetorical ‘red peril’ re-construction of it in the new era, they disguised their neo-colonial hostility to Asian national independence movements – which arguably intensified the anti-communist tone of conservative politics.

In this context, Menzies was always going to act on the ‘domino theory’ fiction. In his reckoning, the notion of the downward thrust of communist China, justified what was, in any case, his government’s race strategy, that of encouraging the establishment of a barrier of US troops in Vietnam to protect white Australia against the perceived threat to regional security posed by sovereign Asian nations.

In Part 2, it becomes clear how the Australian government’s barrier defence against that threat, which it denied, left the force it sent to Vietnam in the dangerous position of confronting enemy armies it could also never name. The First Australian Task Force (1ATF) always remained a coherent fighting force. But we need to understand how official ignorance of the battlefield, arising from the government’s denial of geopolitical reality, projected 1ATF into the strategically incoherent, no-win situation in which it found itself in Vietnam.

The Australian Army and its enemy in Vietnam

In 1948, the formation of the Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) represented the first regular standing army in Australian history. This changed after Menzies announced conscription for overseas service on 10 November 1964, a measure that would be essential to maintain a Vietnam commitment, as well as other commitments in Malaya and Borneo. Almost certainly, Menzies’ November announcement had also anticipated President Johnston’s December request for Australian support in Vietnam and Cabinet’s prompt confirmation of Menzies’ positive response to it. On 17 December, we have indeed seen that Cabinet ratified, in the famous ‘five minutes’, Menzies’ prior decision to offer the US President such support as he had stopped short of requesting: an Australian combat battalion.

Meanwhile, built on limited industrial and recruiting bases, the tough, disciplined quality of the original professional army was retained when national servicemen were included in the small, well-trained, well-armed, and tactically proficient force the government sent to Vietnam. By around that time, the RAR was based on nine infantry battalions. The initial deployment in April 1965 was of a single battalion of about 800 troops, attached to the US 173rd Airborne Brigade at Bien Hoa. In 1966, the force was extended for various reasons to the establishment of a two- and, later, three-battalion Task Force, known as the First Australian Task Force (1ATF) at its Nui Dat Base in Phuoc Tuy Province.[1]

1ATF’s strength peaked in 1969 with some 8000 people – 7672 Australians and 552 New Zealanders. The US army peaked around the same time at over half a million troops. Menzies’ strategic delusion meant that the Australian force, which one rarely sees mentioned in the indexes of American books on the Vietnam War, was a small one with no strategic initiative.

This was especially so when the government’s dependence on conscription to maintain its Vietnam involvement eventually made it fearful of the political backlash if 1ATF sustained significant casualties. The government had proclaimed its aim to prevent ‘the North invading the South’, as the remarkable slogan of the day depicted the strategic problem. In 1966, when the government expanded the battalion into the task force, however, it contradicted its stated reasons for being in Vietnam by wanting a quiet province with little fighting for Australian troops.

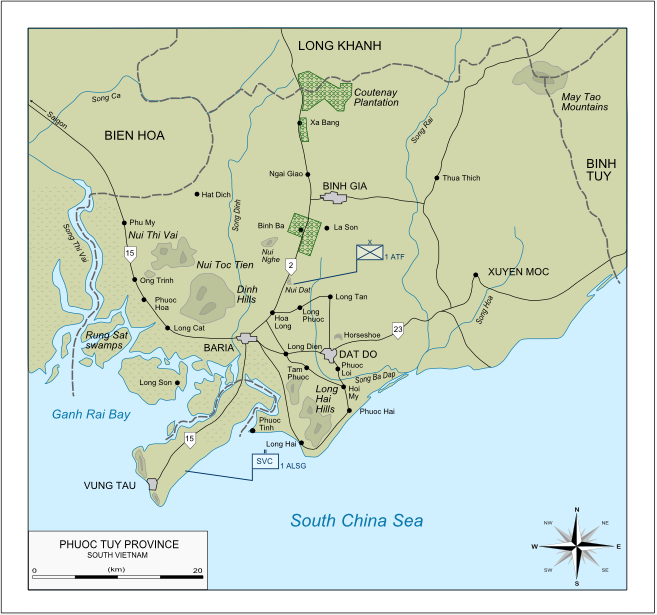

Phuoc Tuy, which was a coastal province in Military Region III south and west of Saigon, seemed to fit the bill. With sizeable rice growing plains, it supported in 1967 a population of some 102 000. With the Long Hai Mountains in the southwest, the most populous area in the centre, and jungle and mountains in the north and northeast, it seemed that 1ATF would face little more than a low intensity campaign fought by small-scale guerrilla units.

The appearance from time to time of regular, main force enemy units in the province was envisaged. Yet these incursions did not necessarily mean battles with large enemy formations that could inflict heavy casualties on 1ATF, as could have been the case in, for instance, Military Region I in northern Central Vietnam. There is, nonetheless, a major qualification to this point: 1ATF’s inability to name accurately its enemy meant that 1ATF would be in a far more dangerous position in Phuoc Tuy than the Australian government could have imagined.

North Vietnam General Vo Nguyen Giap and soldiers after Dien Bien Phu, May 1954 (Vietnam Government)

North Vietnam General Vo Nguyen Giap and soldiers after Dien Bien Phu, May 1954 (Vietnam Government)

Following US and ‘Free World’ usage in Vietnam, 1ATF described its regular main force enemy as the ‘North Vietnamese Army’ (NVA), which overlooked the crucial fact that no state of North Vietnam ever existed. Meanwhile, in 1945, Ho Chi Minh’s declaration of the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) in Hanoi had already fixed the name of the national army: the one that called itself the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN).

Later, in the 1960s, the Australians also adopted the ‘Free World’ term ‘Vietnamese Communists’ (VC) to describe the southern insurgency, which had broken out from around 1957 against the US-backed Republic of Vietnam (RVN) and its army (ARVN) with their capital in Saigon. Yet the term ‘VC’ was also heavily loaded with neo-colonial political bias.

By 1954, the US had been funding 80 per cent of the French colonial war. After the fall of Dien Bien Phu in May, the Geneva Accords in July allowed for the country to be divided at the 17th parallel so that French colonial interests could regroup in the South and leave the country within two years. Reunification elections were then to be held. By September 1954, however, the US had already bankrolled the state of the RVN and its Army (ARVN), and the reunification elections scheduled for 1956 were never held. By 1957, when Vietnamese resistance to the RVN broke out in the South, elements of a civil war existed. Yet, in the 1960s, US political and military influence in southern Vietnam was so great it largely determined the re-emergence of the Vietnamese war of decolonisation.

In December 1960, the ‘National Liberation Front for the Southern Region’ (NLF), which proclaimed itself with DRV backing, called its military wing the ‘People’s Liberation Armed Forces’ (PLAF) – as opposed to ‘VC’. It is notable that in national terms the DRV designation of the ‘southern region’ ruled out recognition of any state of ‘South Vietnam’, just as it did one of ‘North Vietnam’.

In the 1960s, therefore, the emergence of the so-called ‘American War’ represented a continuation or resumption of the war which Vietnamese had won in 1954 against the forces of French colonialism. Altogether, post-1975 Vietnamese histories describe the ‘American’ or ‘Vietnam War’ not as a civil war, but as a part of their ‘thirty-year war of national liberation’.

When it comes to naming armies, basic issues of allegiance and strategy are involved. For the Australian government and high command, the ambiguity of being unable to name PAVN and PLAF was central. The neo-colonial-cum-imperial Australian agenda was bound to suppress those names with the crude substitutes it used, NVA and VC. But that suppression denied Australian war leaders the main portal on the history, political motivation, relationship with society, and operational methods of the national enemy they sent 1ATF to fight in Vietnam.

The strategic incoherence of 1ATF’s position in the Vietnam War followed.

The Vietnamese strategy of protracted, peoples war for national liberation.[2]

Following Chinese models by 1942, Vietnamese communist cadres formed village guerrilla units (du kich) in remote areas in Vietnam to strike fast at enemy targets and disperse among the people. By energising villagers politically, this kind of war often had a larger impact on the local populations than on the stronger enemy, who might only have noticed the strikes as pinpricks. In any case, the method for mobilising people and support, in the form of recruits, rice and intelligence in the protracted war, was the political-military technique of ‘armed propaganda.’

In Vietnamese, the term ‘propaganda’ does not necessarily suggest ‘misinformation’, but something closer to religious or political proselytising. As such, armed propaganda had been going on in Vietnam from 1942, some two years before the official birthday of the PAVN on 22 December 1944, the day its first main force unit was named ‘The Vietnam Propaganda and Liberation Unit.’

Already, village guerrilla forces were the building blocks for the gradual development of semi-regular and regular forces at the provincial, regional, and national levels. By mid-1954, the strategic reflex of dispersing when confronted by stronger forces and then concentrating against weaker ones had enabled the resistance to pump up out of the villages a large national army. By 1954, the resistance had indeed mobilised the notional 50 000 soldiers that constituted the five main force divisions, which PAVN was able to concentrate around the French colonial garrison at Dien Bien Phu. With all the rice, other supplies and intelligence mobilised by the revolutionary resistance, plus the supply of artillery ammunition from China, those divisions finally won their victory over the French garrison and terminated the First Indochina War in a regular, 56-day battle of siege warfare.

Fast forward to the period around 1960 when the peoples’ committees (uy ban nhan dan) in the villages of Phuoc Tuy were supporting the emergence of the NLF and its PLAF to fight ARVN and the forces of American intervention with the support of PAVN. One local Phuoc Tuy Province history, that of Long Dat District (1986), underlines the revival of efforts in 1960 ‘to organise armed forces’ by ‘establishing armed propaganda squads’. On the night of 25-26 November, a few weeks before the formation of the NLF in December, an eight-man squad from the armed propaganda unit ambushed an enemy jeep on Route 44, killing two enemies including an American adviser:

That was the first time the armed propaganda team had killed an American. News of the victory spread and strongly stimulated the movement. Only a few days later, the district armed propaganda unit burst into Tam Phuoc [village] … We got nine [RVN village guards] gave them a long lecture and released them on the spot after collecting their nine rifles and two grenades … In a number of villages the local guards handed over their weapons and went home and returned to work.[3]

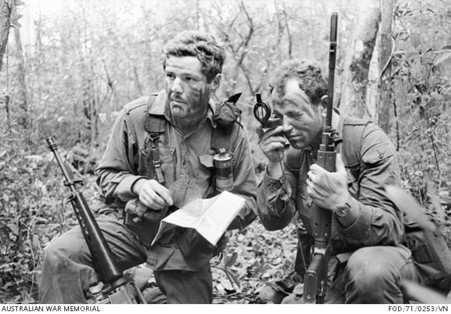

CPL Peter Johnson, Morley, WA, and SGT John Bojarski, Fairfield, NSW, 2RAR /NZ (ANZAC), Phuoc Tuy, Vietnam, May 1971 (AWM). The battalion left Vietnam later in the month.

CPL Peter Johnson, Morley, WA, and SGT John Bojarski, Fairfield, NSW, 2RAR /NZ (ANZAC), Phuoc Tuy, Vietnam, May 1971 (AWM). The battalion left Vietnam later in the month.

By December 1964, local guerrilla units were sufficiently organised to be involved in a major NLF armed propaganda display of the growing incapacity of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). This was when district companies C40 and C45, which had existed since at least 1957, combined with PLAF units from outside Phuoc Tuy Province to rout a large divisional-sized ARVN formation around the Catholic village of Binh Gia inside the province.

On 19 May 1965, Ho Chi Minh’s birthday, C40 and C45 amalgamated to form the local D445 Battalion.[4] From that point, the PLAF-PAVN war against 1ATF in Phuoc Tuy was largely one of armed propaganda, which not only undermined, but turned to PLAF-PAVN advantage the conventional war barriers that 1ATF’s commanders erected in a futile effort to prevent ‘the North invading the South’.

Protecting the enemy: 1ATF’s barrier base and minefield

Operating on that assumption in 1966, Brigadier OD Jackson located the 1ATF base at Nui Dat to the north of the main population centres in the province. This was to protect those centres from the regular main force units he understood to be invading the province from the north. By placing his two combat battalions as shields on the north and north-eastern sectors of the Nui Dat position, he also confirmed the conventional war role of ANZAC forces in two world wars and Korea – thus contradicting the government’s desire that 1ATF should avoid casualties in a low intensity counter-insurgency role.

Following Menzies’ strategic desire for a colonial ‘barrier reef’ to Australia’s north, and McEwen’s reiteration of it in the 1964 Cabinet Meeting, Jackson had set up a barrier base, although he did not call it that. He had overlooked the problem that national resistance was going on among people south of the barrier defence he imagined he had erected. There, south of Nui Dat, a sufficiently large number of people supported the local guerrillas to make the resistance work. This was especially when such resistance implied local support for the regular main force units entering the province. Without realising it, Jackson had positioned his barrier base to protect his enemy.

As the combat developed, historians Bob Hall and Andrew Ross dissect it well in a 2012 essay.[5] They tell us that 1ATF had some 3900 fleeting contacts with guerrilla and other units and 16 ‘landmark battles’. These ‘very few’ battles, which did less damage to 1ATF’s enemy than the mass of fleeting contacts, involved at least an Australian company and supporting arms against elements of D445 Battalion and larger formations, sometimes PLAF 274 and 275 Regiments or PAVN 33 Regiment. Those formations came from outside province and often chose to stand and fight for several hours.

This first happened on 18 August 1966, when a perhaps 2500-strong enemy force, including elements of D445 Battalion and PLAF’s 275 Regiment, appeared near Long Tan village off the perimeter of the Nui Dat base. Fortunately for 1ATF, its enemy encountered some 108 men of D Company 6RAR who stood and delivered. Largely due to their artillery support, well over the 245 enemy bodies counted after the battle – possibly as many bodies again were dragged from the battlefield – compared with 17 Australians who were killed. The 1ATF base was defended. Yet D Company’s tactical victory at Long Tan has largely obscured in Australian writing its enemy’s strategic success.

Australian writers do not usually realise that the mere presence of main force units in the province was enough to warn people not to get close to 1ATF. The sounds of a battle such as at Long Tan, particularly of the artillery, further reinforced that message. With NLF cadres talking up the battle in the villages, the sounds of the gunfire left the people in them believing that the revolutionary side won. As at Long Tan and most other ‘landmark battles’, Hall and Ross provide the evidence-based conclusion that because PAVN-PLAF units were prepared to take infantry casualties in Phuoc Tuy, they ‘unreservedly won’ the political struggle for the ‘hearts and minds’ of the people.

The very presence of 1ATF in Phuoc Tuy had transformed it into a far more dangerous province than the government had imagined. That was especially so from 1967 when the second 1ATF commander Brigadier Stuart Graham still did not know who his enemy was. In June that year, Graham made a disastrous blunder stemming from official ignorance of the battlefield.[6] As he saw it, his force was too small for the scale of the security problem it faced in the large province. The government, which was famously unable to give 1ATF instructions about how it might create security, also failed to provide Graham with the extra troops he asked for. To free up his small force for offensive patrolling and other tasks he resorted to a conventional war strategy, which he knew was risky but felt obliged to employ.

His idea was to lay an 11 kilometre long ‘barrier minefield’ containing some 20 000 lethal M16 landmines around Dat Do village. He calculated that the minefield would extend the barrier function of the Nui Dat base by shielding the villagers around Dat Do from ‘NVA’ main force units, invading from the north. But, of course, this solution to his tactical problem greatly exacerbated it. In effect, the barrier minefield compounded the problem of Jackson’s barrier base by arming 1ATF’s enemy.

Graham left the mine field unguarded in a situation where he did not understand that, because the peasants in the villages were his guerrilla enemy, they – mainly young women at first – would enter the minefield and, feeling around with their toes, find the mines and begin the process of lifting over 5000 of them. The guerrilla enemy, which 1ATF had not noticed, and which could not in any case have put a glove on 1ATF with its discipline, training, and heavy weapons, now armed itself with all the high explosive ordnance it could use to turn against 1ATF from its own minefield. Local guerrillas called the minefield their ‘weapons store’, just as 1ATF soldiers said it was.

Within a few weeks the ‘barrier minefield’ was breached and, thereafter, 1ATF was much preoccupied with the realisation that it had been attempting to protect its enemy. By 1971, M16 mines from the 1ATF minefield had killed and mutilated more than 300 Australian and a further 200 Allied soldiers and civilians. This tally was roughly ten percent of all Australian battle casualties in the war, rising to 80 per cent for some major operations. The tactical implications were also far reaching. Operations were skewed by, for instance, the creation of no-go areas and the reduction of rates of advance for infantry patrols to 100 metres an hour as the scouts prodded with their bayonets for mines. 1ATF’s enemy was also able to successfully defend its base areas, most notably in the Long Hai Hills, with M16 mines.

Some idea of the chaos resulting from the projection of the high command’s ignorance of its enemy on 1ATF’s incoherent barrier strategy thus follows.

(Right) The M16 ‘Jumping Jack’ Mine primed with an M106 fuze, and (left) an anti-lift device consisting of an M26 grenade and an M5 pressure release switch. The ensemble awaits installation in the mine hole to the right of the shadow at the base of the mine in May 1967. The anti-lift device would be placed in the hole first, the mine sat on top of it, and the spoil packed back in the hole around the ordnance. The prongs on the fuze would be just below the surface and camouflaged with a light sprinkling of dirt. (Photo: courtesy Dick Beck).

(Right) The M16 ‘Jumping Jack’ Mine primed with an M106 fuze, and (left) an anti-lift device consisting of an M26 grenade and an M5 pressure release switch. The ensemble awaits installation in the mine hole to the right of the shadow at the base of the mine in May 1967. The anti-lift device would be placed in the hole first, the mine sat on top of it, and the spoil packed back in the hole around the ordnance. The prongs on the fuze would be just below the surface and camouflaged with a light sprinkling of dirt. (Photo: courtesy Dick Beck).

Some strategic chaos

One could chronicle 1ATF’s strategic incoherence from at least the time of Brigadier Graham’s appreciation of the need to lay the barrier minefield. The worst run of Australian mine casualties then followed in a series of operations between 8 May and 15 August 1969, which Frank Frost’s classic history of 1ATF found ‘did not produce any conclusive result’. A local Vietnamese history noted many ‘armed propaganda’ successes and described how ‘the cadres and soldiers of Long Dat turned the Australian M16 mines into weapons to kill Australians’. Nineteen Australians were killed and at least 80 wounded in the 13-week period, while 1ATF inflicted negligible casualties on its enemy.[7]

Here is another, more detailed example taken from Chapter 14 of The Minefield. On 18 February 1970, the 8th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (8RAR), cornered D445 Battalion or most of it in a re-entrant. Destruction of the battalion would have been a serious military setback for 1ATF’s enemy. With Canberra breathing down its neck and perhaps seeking consciously to avoid casualties, however, Headquarters 1ATF ordered a B52 air strike on the enemy battalion, which 8RAR’s Commanding Officer, Keith O’Neill, did not want. His troops would have to pull back 3000 metres, the safety distance for such a strike, and he feared that D445 would get away.

It did. Intersecting with that outcome on ‘Black Saturday’ 28 February 1970 was, then, the worst mine incident in 1ATF history, involving only two M16 mines from the 1ATF minefield.

The Long Hai Hills were one of D445’s base areas. O’Neill thus sent 1 Platoon under Sergeant Bill Hoban to ambush some tracks leading into those hills. Around 11. 00 am, the patrol stopped near the top to rest and removed their packs. Thereupon, one of the soldiers dislodged a rock and revealed a booby-trapped grenade, which did not go off. Sapper Terry Binney, who I interviewed in 2002, had a look, returned to his pack to get some plastic explosive to blow the grenade and, suddenly, he thought, ‘”Fuuuck” – I’ve heard a “click”. There must be a mine beside my pack. It exploded. Dirt and shit flew up and I got thrown into the air. A bone came out of the bottom of my boot. I was walking for a moment, too shocked to feel pain, and collapsed near the radio.’

In an instant, the scene had changed violently: eight were killed and 13 wounded, some screaming in agony. The blast probably blew Binney above most of the shrapnel, which also missed some as close as two metres away but killed and wounded many 30 or 40 metres away. Bill Hoban, who was in talking distance of Lance Corporal Bob D’Arcy, looked at D’Arcy and dropped dead. Another soldier, who was wounded as he was blown into the air, watched and heard a young soldier die as a jet of blood burst from his ear.

Binney distinguished himself, despite his heavy wounds. Although losing, as he put it, ‘the Popeye tattoo on my foot’, he instructed another soldier named Barrett to use the mine detector to clear a path to a Landing Zone from where medical evacuation helicopters known as ‘Dustoffs’ could evacuate the wounded. While Barrett did this, a ‘Dustoff’, came in with another soldier named Miller being winched down from the air into the position. Then, Barrett stepped back out of the area he had cleared and stood on the second M16 mine. ‘And “CRUMP”’, Binney told me. ‘He got it up the back and died almost immediately. The chopper took some shrapnel and had to clear out with Miller dangling on the winch, wounded. That would have been a ride!’, said Binney. Then, no one probably heard, as he shouted into the radio handset, ‘Get the fucking Dustoffs in’. With total casualties of nine killed and 15 wounded, the platoon had been wiped out.

Within five hours of this monstrous event on 28 February, there was another. This time, 1ATF headquarters, which had inadvertently facilitated D445’s escape ten days before, ordered 6RAR ‘to destroy D445 … Battalion’. But what happened around 5 pm on 28 February some 20 kilometres northeast of the Long Hai Mountains was that D445 caught 2 and 3 platoons from 6RAR with heavy small arms, machine gun, and rocket propelled grenade fire in a bunker system. Fifteen soldiers were wounded before the platoons were extricated.

In March and April, the casualties mounted in several other bunker contacts and mine incidents with many variations on the horror as 1ATF units were yet again ordered ‘to destroy D445 Battalion’. On 15 March, for instance, Trooper NP Tognolini ran his Armoured Personnel Carrier over an 18-kilogram anti-tank mine near Xuyen Moc in the hunt for D445. At least ten were wounded, some seriously. Tognolini lost a foot and had his other leg trapped under the stricken vehicle as fuel sprayed over it. He later died from burns and the trauma of the double amputation 8RAR’s Medical Officer Bill Josephson had to perform to cut him from under the vehicle, ‘with a raging fire coming out of the turret’.

On 22 April, there was yet another bunker contact, this time after 1ATF ordered 7RAR ‘to destroy D445 Battalion’. This time, D445 Battalion lured B Company, 7RAR, into some fierce crossfire about 13 kilometres east of Nui Dat. B Company sighted two enemy, and a reconnaissance party led by Lieutenant Doug Gibbons from 5 Platoon followed them up. Suddenly, at 1.39 pm, while moving through bamboo thickets, the party received heavy AK47 fire from bunkers at a range of 15 metres. The volume of enemy fire intensified, and the forward scout, Private Colin Tilmouth, was shot in the throat. Under covering fire from his patrol, Gibbons rescued Tilmouth. Company HQ and 4 Platoon attacked the bunkers to help extricate the reconnaissance party and were met by fierce small arms, 60 mm rocket and rocket propelled grenade fire which hit one of the helicopter gunships also attacking the position. At 6.20 pm the attack was suspended. Tanks were brought up to the start line to resume the attack in the morning. By that time, the enemy had withdrawn, leaving four bodies in the position that turned out to contain 18 bunkers. Six Australians were wounded and one, Pte RR Hughes, later died of wounds.

In the end, 89 1ATF soldiers were killed and wounded in operations that can be related to official reticence over casualties and, in any case, to the failure to destroy D445 on 18 February. If, as 8RAR had wanted, it had attacked decisively with its great advantages in heavy weapons, tanks, and artillery, it is reasonable to conclude that it would have taken far fewer and, perhaps, relatively negligible casualties.

Australian base, Nui Dat, 1971 (AWM)

Australian base, Nui Dat, 1971 (AWM)

Some staying power

At the same time, we must not forget that 1ATF always remained a coherent fighting force. Frank Frost, myself and Bob Hall have all emphasised the ‘tactical proficiency’ of the disciplined, well-trained, and well-armed 1ATF and its capacity to inflict heavy casualties on its enemy.[8] A more recent 100-page ‘Research Note’ (RN), which Ernie Chamberlain produced in 2020 now permits us to crosscheck that view and drive home its meaning.

RN is called ‘Communist Views of the 1st Australian Task Force’.[9] It compiles Chamberlain’s translations of Vietnamese resistance commentaries on 1ATF from during and since the war. As such, it presents serious tactical observations of 1ATF interspersed with denigration of and loose commentary about the force. From our perspective, the tactical observations are the most relevant parts of RN.

One exception is worth mentioning: the frequent denigration of Australian forces as ‘imperialist’ mercenaries and the like. That designation would not accurately reflect the ANZAC self-identification of Australian soldiers in Vietnam. Yet it does underline the basic political and strategic disposition from which their enemies disparaged them; namely, the primacy of the Vietnamese anti-imperial and anti-colonial struggle for national independence (as distinct from their communist goals, which were also asserted). By implication, the neo-imperial nature of Australia’s involvement in the war surfaces once more.

Meanwhile, let us focus on the credible Vietnamese perception of effective Australian operational methods, two examples of which are enough to serve our purposes here.

One is from a 2013 history of D440 Battalion, which explains that Australian forces:

were expert at ambush tactics, small-scale assaults at half-section and section strength into our rear areas. They also used artillery to fire interdiction missions … and they adapted themselves quickly to the tropical climatic and weather conditions. They created many difficulties for the local Revolutionary Movement, and we suffered heavy casualties.’[10]

The other is from a 2010 Binh Ba Village history:

In the area of the Bau Sen base [north of Duc Thanh], the enemy’s artillery fired continuously night and day. The US and the Australian commandos ambushed all the ways in and out of the base, and the enemy’s mines, and all types of boobytraps were laid in the jungle and along all the trails and our liaison routes. Route 2 from Cam My past Xa Bang down to Binh Ba became a road of blood. The Australians camouflaged themselves and ambushed both day and night in the thick and difficult jungle as well the lake edges. Many district cadre and plantation cadre were killed.[11]

These remarks represent a somewhat prevalent, considered Vietnamese picture of an aggressive Australian force with a high degree of training and discipline. The main 1ATF methods, which its enemy’s commentary tends to confirm, were stealthy, small-unit tactics, those of an infantry section, platoon, or company patrolling through the jungle – taking ‘short cuts’ as the Vietnamese sometimes observe, on compass bearings through the scrub and using good field craft, rather than moving as the local forces usually did along beaten tracks.

Phuoc Tuy province (Wikipedia)

Phuoc Tuy province (Wikipedia)

The Vietnamese perception was also one in which the salience of ‘artillery’ support for 1ATF infantry operations is clear. 1ATF’s artillery was used in all 16 ‘landmark battles’, often to great effect, as at Long Tan. All 1ATF patrolling went on within artillery range (11 000 metres), and was used in heavy contact, including in bunker systems. Artillery was also used for ‘harassing’ fire, in which the guns speculated by firing at targets of possible enemy activity. In relation to the 3900 small contacts registered by Hall and Ross, artillery and mortars were little used.

In another research paper, Chamberlain offers an estimation of the casualties that 1ATF inflicted on D445.[12] Apparently, in his words, ‘D445’s strength in August 1966 was 392 – but was down to 157 in September 1971 when 1ATF began to withdraw’. How, then, assuming these figures are accurate, did D445 manage this 60 percent depletion in its strength over some five years?

While the paper on D445 stops short – as RN does – of conceptualising PAVN-PLAF’s strategy of protracted war for national liberation, the paper’s tactical preoccupations go a long way to answering that question. Chamberlain stresses that, indeed, the battalion ‘was “dispersed” into three companies and attached to the VC districts’. Such was indeed the PLAF-PVN strategy as well as the tactic we raised earlier of dispersing in the face of stronger forces and concentrating when they were weaker – all within the process of mobilising people in the protracted, interactive small and large unit people’s war.

We may say that the refuge D445 found in the villages of Phuoc Tuy enabled it to maintain the unit in decline. Hence, the armed propaganda actions we have instanced in the province. In 1969, village guerrillas went on with the ‘deliberate mine battle’. In 1970, we saw that D445 could still out-manoeuvre and inflict heavy casualties on 1ATF. In 1972, Chamberlain notes, D445 returned to full strength when 1ATF left the province – as the strategy of protracted war always predicted it would.

Chamberlain’s translations and research help us to dovetail both sides of the war. His work clearly justifies a conclusion that 1ATF infantry operations supported by artillery and mortars ‘created many difficulties for the local Revolutionary Movement, and we suffered heavy casualties’. He confirms the effective tactical side of 1ATF military operations, even as they were afflicted with strategic incoherence. He underlines the political-military capacity of that enemy to remain strategically alive, even in tactical military defeat.

RN thus drives home the essential ambiguity of the no-win situation into which the Australian government sent its army in Vietnam. That document helpfully draws our attention to the flip side of the incredulous American-Australian post-war observation that ‘we won every battle but lost the war’. As a compilation of communist observations of 1ATF’s skillful and effective tactics, RN could not make it clearer that the Vietnamese resistance lost many battles and won the war.

Conclusion

The historical significance of 1ATF lay in its training, discipline, heavy weapons, particularly artillery, and tactical proficiency, because they were the factors that kept it functioning as a coherent fighting force in an incoherent strategic setting.

Dependence on the US position in Vietnam to counter a threat it could not name was always the frame for Australia’s involvement in the war. 1ATF would then erect barrier defences against an enemy it could not name. Many skewed operations and grievous casualties followed, especially after the laying of the ‘barrier minefield’. As the Vietnamese resistance strategy of protracted peoples’ war anticipated, 1ATF would inevitably withdraw – once the Americans were forced to announce their withdrawal. 1ATF withdrew by December 1971, almost three and a half years before the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975 marked the end of the war.

1ATF was strong enough to surmount the dangers it faced in Phuoc Tuy Province. But even by way of encouraging and supporting US escalation of the war in 1965, it could never have done what the Commonwealth secretly sent it to do: reverse the process of decolonisation in Vietnam. It was always in a no-win situation.

The Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV) was the first Australian Army unit in Vietnam in 1962 and the last to leave in 1972. Here, on 16 December 1972, members of the AATTV, Captain Greg Lockhart (left) shaking hands with Warrant Officer Brian Ranson, as Warrant Officer John Whipp looks on immediately after they participated in the Australian Army’s last parade in Vietnam (supplied). More on AATTV.

* Greg Lockhart is a Vietnam veteran and an historian. Formerly of the Australian National University, he is author of Nation in Arms: The Origins of the People’s Army of Vietnam (1989), The Minefield: An Australian Tragedy in Vietnam (2007) and, lately, essays on Australian history. He is co-translator with his wife Monique of The Light of the Capital: Three Modern Vietnamese Classics (1996). His memoir Weaving of Worlds: a Day on Île d’Yeu (2022) is forthcoming. Use the Honest History search engine to find other work by him.

Endnotes

[1] Frank Frost, Australia’s War in Vietnam (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1987) is still the best book on 1ATF.

[2] For a full discussion see Greg Lockhart, Nation in Arms: the Origins of the People’s Army of Vietnam (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1989).

[3] Long Dat, 94, with other examples of ‘armed propaganda’ appearing on 48, 72 quoted in Lockhart, The Minefield: an Australian Tragedy in Vietnam (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2007), 32.

[4] Lockhart, The Minefield, 32

[5] Bob Hall & Andrew Ross, ‘Landmark battles and the myths of Vietnam’, in Craig Stockings, ed., ANZAC’s Dirty Dozen (Sydney: NewSouth, 2012), 186-209.

[6] This story is told in Lockhart, The Minefield.

[7] Frost, Australia’s War, Ch. 6; Long Dat, Ch. 8; Lockhart, The Minefield, Chs. 10-11.

[8] Frost, Australia’s War, 1987, 75-6, 135-36 initiated the argument, which I and Bob Hall reinforced in various places between 1990 and 2012.

[9] Written at Point Lonsdale and addressed on 28 February 2020 to the Australian War Memorial, Canberra. Some 20 per cent of the 100-page text is devoted to bibliography, annexes, and notes. A considerable part of the work also covers enemy denigration of and wildly inaccurate remarks about 1ATF, especially its casualties.

[10] RN, 4.

[11] RN, 71.

[12] EP Chamberlain, ‘Memorial for our old Foe’, The Vietnam Veterans’ Newsletter, December 2019.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.