‘Lest We Forget comes out of the West’, Honest History, 7 October 2014

Paddy Gourley* reviews Bobbie Oliver & Sue Summers, ed., Lest We Forget? Marginalised Aspects of Australia at War and Peace, Black Swan Press, Curtin University, Perth, WA, 2014

_____________________________________________________________________

This book is the latest in the series Studies in Australia, Asia and the Pacific, that has drawn largely on the work of people associated with the Australia-Asia-Pacific Institute at Curtin University in Western Australia. As well as an introductory chapter, it contains essays dealing with matters the editors say ‘have received relatively little attention in the booming literature of Australia’s war experience in the 20th century’.

The most obvious thing to say about this collection of essays is that it is timely, we now being at the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I and with that mark coming up next year for the Gallipoli campaign. If form is anything to go by, it’s a good bet that not all about next year’s Anzac Day will be as good as it could be. While Anzac commemoration is often done very well, it is also attracts its fair share of false and exaggerated sentiments and claims.

When the respected war historian, Hew Strachan, says that Australian, New Zealand and Turkish ‘national identity was forged at Gallipoli’, it is perhaps understandable that others make overblown claims about the consequences of Australia’s experience of military conflict. Thus it is probably better only to be puzzled when the current Director of the Australian War Memorial, Dr Nelson, says that ‘[n]o group of Australians … has worked harder to shape our values and beliefs, the way we relate to one another and see our way in the world’ than past and present members of the defence forces.

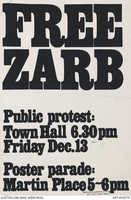

Anti-conscription poster c. 1968, referring to resister John Zarb (Australian War Memorial ART V03070). The poster is one of just two items under the heading ‘conscientious objectors’ in the Art collection of the Australian War Memorial .

Anti-conscription poster c. 1968, referring to resister John Zarb (Australian War Memorial ART V03070). The poster is one of just two items under the heading ‘conscientious objectors’ in the Art collection of the Australian War Memorial .

The point is that both Strachan and Nelson are reading too much into the direct experience of military conflict and military life. The national identity of any country can’t be ‘forged’ by a particular military campaign. It is inevitably composed of a host of experiences that play out over many years. And it would have occurred to hardly anyone in the defence forces that they were actively working ‘to shape our values and beliefs’. In the main, values and beliefs are the product of vast influences that have nothing to do with the military.

True, military conflict and the defence forces have had an effect on making Australia what it is. Distorting or exaggerating that effect is bad history and it leaves inadequate room to acknowledge properly the huge variety of contributions of others to the country’s development.

In a foreword to Lest We Forget Peter Stanley says a strength of the Australia-Asia-Pacific Institute ‘has been its members’ willingness to explore contentious areas of scholarship, to pose difficult questions and offer responses that might not always be regarded as comforting’. That’s what this collection of essays does.

Sue Summers provides a history of World War I trooper Frank Bolger who, after being shot in the chest in the Battle of The Nek was discharged; the bullet was not removed as it was too close to his heart. He was discharged as permanently unfit and given a pension. Bolger went to live in the vast backblocks of Western Australia, where he faced a continuing struggle over his benefits with government authorities who, Summers says, were ‘ill prepared for the immensity of the repatriation task’.

Lenore Layman examines the circumstances of the hundreds of thousands in so-called ‘reserved occupations’ who were restricted from military enlistment in World War II. Many of those affected may have preferred it to be otherwise but, without their efforts at home, a contribution to the allied war effort would not have been possible. Layman says that this ‘was not the stuff of which legends were made’ and that those in the ‘reserved occupations’ have found ‘no meaningful place in post war commemoration’.

Bobbie Oliver looks at conscientious objectors in the national service schemes between 1950 and 1972. Oliver notes that the Bishop of Bendigo claimed that the war in Vietnam was ‘a holy war against Communism; therefore conscription was justified’. With such egging-on many conscientious objectors to service in Vietnam were treated firmly by the system and often more so by the misguided patriots of the white feather brigade. The notion of conscientious objection as a part of war commemoration may be a testing one but there’s a lot to be said for remembering war in all its dimensions.

In their consideration of ‘Anzac Day media representation of women in Perth 1960-2012’, Robyn Mayes and Graham Seal say that women ‘have a range of variously contentious and shifting relationships with Anzac Day’ and have tried to ‘expand its meanings not least as a day for critical appraisal of the wider, gendered costs and sacrifices inherent in war’. It’s a front on which there may have been some give.

GW Lambert, West Mudros rest camp, Lemnos, 1919 (Australian War Memorial ART 02823)

GW Lambert, West Mudros rest camp, Lemnos, 1919 (Australian War Memorial ART 02823)

Finally, John Yiannakis laments what he sees as the ‘marginalization of Lemnos in the history and mythology of Gallipoli’ and wants this Greek island staging post to have a firmer ‘place in the story of Anzac’. He may have a point but there may be limits to the extent to which Gallipoli’s myths can be taken.

In summary, the Lest We Forget collection of essays is a reminder of things not so much at the heart of military encounter yet critical to it and that the burden of military endeavour and its consequences stretch well beyond those on conflict’s front lines. To the extent that Anzac Day has become an occasion to commemorate Australia’s involvement in all wars, these essays suggest it would be as well if it could more fully encompass the commemoration of our military experience.

Lest We Forget is a well-edited book with a useful introductory chapter from Oliver and Summers. Its essays are well written and contain extensive endnotes. Most of all they are interesting stories about parts of Australia’s history that deserve greater prominence.

* Paddy Gourley is a former senior Commonwealth public servant.