‘Keepers of the flame: why do the people who control our war memorials look so different from the rest of us and why does this matter?’ Honest History, 7 June 2016 updated

Contents

The Australian War Memorial Act 1980 and its history

The composition of the Memorial Council since 1980

A comparison with war memorials in Australian states

A comparison with war memorials in other Commonwealth countries

__________________________

A few weeks ago, two new members were appointed to the Council of the Australian War Memorial. They are a retired RAAF nurse, female, aged about 40, and a Victoria Cross recipient, aged 32. The new members join a body that includes three male septuagenarians, two male generals, a male air marshal, a male vice admiral, a retired female brigadier, a retired male colonel, and two women with portfolios of interests in philanthropy, academia and business. Then there is the Director of the Memorial, who is not formally a member of the Council but attends all of its meetings. The current Director is a former Commonwealth minister, Leader of the Opposition, and ambassador.

The arrival of new Council members offers an opportunity to compare the composition of today’s Council with its own history and with the make-up of similar bodies in other jurisdictions. If, as we are told by the current Director, ‘Every nation has its story. This is our story’, it would be reasonable to expect that the people who control the telling of the story should look something like the nation whose story the Memorial tells. If, on the other hand, the members of the Memorial’s Council are unrepresentative it is likely that the story the Memorial tells will be unrepresentative also and perhaps self-serving.

The Australian War Memorial Act 1980 and its history

Under section 9 of the Act, the War Memorial Council ‘is responsible for the conduct and control of the affairs of the Memorial and the policy of the Memorial with respect to any matters shall be determined by the Council’. Section 10 of the Act says that the members of the War Memorial Council shall be the Chiefs of Navy, Army and Air Force and not less than eight or more than ten other members ‘appointed by the Governor-General having regard to their knowledge and experience with respect to matters relevant to the functions of the Memorial’. Finally, under section 20 of the Act, the Director of the Memorial ‘is the chief executive officer of the Memorial and shall, subject to and in accordance with the general directions of the Council, manage the affairs of the Memorial’. So the Council controls, the Director manages; the Council is in charge.

Australian War Memorial Museum, Sydney, c. 1925 (AWM P08655.003)

Australian War Memorial Museum, Sydney, c. 1925 (AWM P08655.003)

The legislated requirement for three ex officio military members has been in place since 1952, 64 years, though the service chiefs were frequently appointed to the then Board of Management even before that date. The formal inclusion of the service chiefs on the Board of Management was supported by the then Director of the Memorial, JL Treloar, who argued that, ‘as matters affecting the Services arose regularly, it would be an advantage if the Chiefs were fully aware of the Memorial’s needs’.[1] This would have made sense just a few years after World War II, as the Memorial was building up its collection, drawing upon artefacts from that war.

When the old Board of Management was replaced by a Board of Trustees in 1962, the old Board included two generals, two admirals, an air marshal, an air vice marshal – three of these gentlemen were ex officio and three were retired – plus a former president of the then RSSAILA and the venerable CEW Bean. The retired officers included Rear Admiral Sir Leighton Bracegirdle (Ret’d), whose career in the defence forces had begun in 1898 and who had served on the Board since 1938.

The composition of the Memorial Council since 1980

Apart from ex officio military members what has been the background of the members of the Memorial’s Council? The table below analyses the composition of the Council at five-year intervals from 1985. The final entry is for the Council at 1 July 2016 to take in the two most recent appointments (now updated to July 2018).

| Year | Total members | Military (including three ex officio) | Civilian |

| 1984-85 | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| 1989-90 | 12 | 5 | 7 |

| 1994-95 | 13 | 6 | 7 |

| 1999-2000 | 13 | 8 | 5 |

| 2004-05 | 13 | 8 | 5 |

| 2009-10 | 12 | 7 | 5 |

| 2014-15 | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| 1 July 2016 (July 2018) | 13 (13) | 9 (9) | 4 (4) |

Source: Australian War Memorial Annual Reports from 1984-85 on. Where there was a change of member during the year, we have counted the member who was in office at the end of the year. We have counted as ‘military’ members only those who were designated as ‘Retired’ from military service or who listed a military decoration. In two cases, where the member had served in the defence forces but later became a parliamentarian, and one case where a former serviceman later became a bishop, we have counted the member as ‘civilian’.

The table shows that in five out of seven sample years (six out of eight if we include 2018), members with a military background have made up a majority of the Council. Given that only three positions are ex officio military, it is clear that these majorities have come about through appointments by the Minister of the day.

Further, the great bulk of these non ex officio military appointments have been of former senior officers; there has always been a lot of brass in Memorial Council meetings. (The two 2016 appointments of Bown and Keighran were a welcome change from the emphasis on seniority.) Adding to the military cast was the presence between 1996 and 2012 of Major General Steve Gower AO (Ret’d) as director, followed in that role by the Hon Dr Brendan Nelson AO, a former Minister for Defence.

The Council from 1 July 2016 (with 2018 changes noted below) comprises the following individuals (ages as at 2016):

- Kerry Stokes AC, businessman and philanthropist, Chairman, age 75

- Vice Admiral Tim Barrett AO CSC RAN, Chief of Navy (ex officio) [replaced July 2018 by Vice Admiral Michael Noonan AO ex officio]

- Wing Commander Sharon Bown (Ret’d)

- Lieutenant General Angus Campbell DSC AM, Chief of Army (ex officio) [replaced July 2018 by Lieutenant General Rick Burr AO DSC MVO ex officio]

- Les Carlyon AC, author and journalist, age 73

- Brigadier Alison Creagh CSC (Ret’d), Executive Director, Spirit of Anzac Centenary Experience (a War Memorial project), other community roles [replaced July 2018 by Colonel Susan Neuhaus CSC (Ret’d)]

- Air Marshal Leo Davies AO CSC, Chief of Air Force (ex officio)

- Rear Admiral Ken Doolan AO RAN (Ret’d), National President of the RSL, former Chairman of the Council, other community roles, age 77

- Corporal Daniel Keighran VC, now of the Army Reserve, private sector and community roles

- James McMahon DSC, DSM , Commissioner of Corrective Services, Western Australia, community roles, formerly commanding officer, Special Air Service Regiment

- Major General Greg Melick AO RFD FANZCN SC, Army Reserve since 1966, barrister, community roles

- Jillian Segal AM, lawyer, company director, community and university roles, Chair of the General Sir John Monash Foundation [replaced June 2017 by Margaret Jackson AC]

- Josephine Stone AM, lawyer, company director, community roles.

Sir Leighton Bracegirdle (Wikipedia)

Sir Leighton Bracegirdle (Wikipedia)

We have not attempted an historical analysis of the ages of Council members, although we believe the average age of the current Council is approximately 57 years. Corporal Keighran at 32 years of age may well be the Council’s youngest-ever member though we have not checked this. Nor have we looked at the occupational background of Council members earlier than the current Council or the historical gender balance, though the current tally of four women out of 13 may be slightly higher than usual.

Nor are we claiming that, because a member has been a soldier or a sailor (or a business person or a lawyer) that he or she will act on the Council only as a representative of that profession or that his or her motivations will derive only from the time spent in that profession. People are more complicated than that.

On the other hand, we do suggest that military officers, senior ones in particular, are the custodians of a legacy, encapsulated as ‘the Anzac tradition’ or a similar formulation, which perpetuates a particular view of military service.[2] It is not surprising that these men – almost all of them have been men – would use their positions on the Memorial Council to promote a corporate ethos which suffuses the past and present of our defence forces – and serves their future, given that how the Memorial presents military history will influence defence recruitment.

A comparison with war memorials in Australian states

Anzac Memorial, Hyde Park, Sydney

Under the Anzac Memorial (Building) Act 1923, the Trustees of the Anzac Memorial are required to maintain and conserve the Memorial and to preserve the memory of those who have served their country in war. The Premier of New South Wales is the Chair of the Trust, though the role is normally delegated to the Minister for Veterans’ Affairs. The State President of the New South Wales Branch of the RSL is Deputy Chair and the other Trustees are the Leader of the Opposition, the Lord Mayor of Sydney, the Secretary of the Department of Education, the State Librarian, the State Architect, and representatives of veterans and the community. The official representatives tend to nominate proxies.

Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne

The Victorian model is at once more militarised and somewhat more complex than the New South Wales one. Under the Shrine of Remembrance Act 1978 the Shrine Trustees are responsible for the care, management, maintenance and preservation of the Shrine and the land around it. There are ten Trustees, including a retired air vice marshal (Chairman), a retired major general (representing the RSL), two colonels, a wing commander (representing Legacy), the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, and four civilians. There are also five Life Governors and seven Governors, whose functions are ceremonial. Eleven out of 12 of these individuals are current or retired members of the Defence Force.

A comparison with war memorials in other Commonwealth countries

Canadian War Museum

The Museum is one of three museums within the Canadian Museum of History, which is a Crown Corporation under the Museums Act. The Corporation has a Board of Trustees with eleven members, selected from across the country and appointed by the relevant Minister. While the most recent Chair of the Board (deceased April 2015) was a retired senior military officer, the remaining Trustees are predominantly business people, philanthropists, academics and community activists. The Trustees’ biographies disclose virtually no military experience. (One Trustee is ‘an active member of the Royal Canadian Legion and the Atlantic Branch of the Black Watch Association’.) Three of the Trustees are women.

Reporting to the Board, there is a Canadian War Museum Committee, which includes members of the Board and representatives of veterans’ associations. The Committee ‘provides advice on matters related to the Canadian War Museum’ but the Corporation, including the War Museum, is governed by the Board of Trustees.

The key feature of the Canadian system is the grouping under the Museums Act of six main museums and galleries (as well as the museum of history, including the War Museum, there is the National Gallery and the museums of nature, science and technology, human rights and immigration). This is fundamentally different from the Australian model, where the War Memorial sits by itself in the Veterans’ Affairs portfolio which, in turn, is part of the Defence portfolio. This has been the case since 1984, though the arrival of the Memorial in its new portfolio was not without considerable controversy.[3]

Pukeahu National Memorial Park, Wellington, April 2015 (Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage)

Pukeahu National Memorial Park, Wellington, April 2015 (Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage)

National War Memorial, Aotearoa New Zealand

The National War Memorial, Pukeahu Park, Wellington, is controlled and maintained directly by the relevant minister, under the National War Memorial Act. The Act provides for a National War Memorial Advisory Council, whose current members are a retired rear admiral as Chair, a retired air vice marshal, a retired major, the chief executive of the relevant ministry, and the president of the Royal New Zealand Returned Services’ Association (RNZRSA). This membership reflects the terms of the Act, which provides for one ministerial appointee, two nominees of the RNZRSA, a senior serving or retired officer of the Defence Force, and the chief executive of the ministry. Currently, just one of these five is a woman.

Superficially, the New Zealand model looks even more military-dominated than the Australian War Memorial set-up but it gives the military representatives an advisory role only. Power resides with the minister and his or her department (Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage). The location of the commemorative function within a wide-ranging culture ministry is another fundamental difference from the Australian model. New Zealand looks like Canada in that respect.

Imperial War Museum(s), United Kingdom

The Imperial War Museum is actually five museums across the UK, with the flagship IWM located in London. The IWM is subject to a number of pieces of legislation, one of which (the Imperial War Museum Act 1920) establishes the Board of Trustees. There are currently 22 Trustees, comprising a president (appointed by the Queen), and appointees of the prime minister (ten members), the foreign secretary (two members), the secretary for defence (one member), the secretary for culture, media and sport (one member). Then there are ex officio the high commissioners of Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa and Sri Lanka. The Trustees ‘have corporate responsibility for the general management and control of IWM’ and they meet quarterly.

The current president of the Board of Trustees is the Duke of Kent, whose position seems to be formal only. Leaving aside the Duke, the seven high commissioners and a vacant position, there are 13 Trustees left. The chairman is an air chief marshal who is about to become Chief of Defence Staff, his deputy is a retired general, and there is a retired rear admiral among the other members. That leaves nine civilians, including Lord Ashcroft of Chichester (who has a colourful history and interesting tax arrangements), historian Professor Sir Hew Strachan, a former head of the Secret Intelligence Service, a defence bureaucrat, and people active in academia, the arts and business. Just two of these 13 Trustees are women and none of the ex officio high commissioners is female.

Altogether, the IWM list gives off an air of what used to be known around Whitehall as ‘the great and the good’. With only three military men out of 13 non-royal appointees, though, this is a much less militarised body than the Council of the Australian War Memorial, however, or the New Zealand Council (which is advisory only) although it is more militarised than the Canadian Board of Trustees (which has a range of responsibilities apart from the War Museum). Like every other body we have looked at the IWM Board is overwhelmingly male.

As for portfolio arrangements, the IWM is an executive non-departmental public body under the Department for Culture, Media and Sport so, as in Canada and New Zealand, the commemorative institution is formally within the culture portfolio. The culture secretary, however, has only limited powers of appointment to the Board of Trustees and the status of the IWM is clearly rather more than a cultural institution. A study of its Minutes, available online, albeit in redacted form, might reveal more of its internal politics. Making Council Minutes available is a practice the Australian War Memorial might well consider.[4]

Imperial War Museum, London (Visit London)

Imperial War Museum, London (Visit London)

Who runs the show?

In 1968, the minister then responsible for the Australian War Memorial, Peter Nixon, tried to persuade the then Chairman of the then Board, Lieutenant General Sir Edmund Herring (Ret’d), aged 76, that the Board needed ‘more broader representation’. Sir Edmund dissuaded him.[5] Almost 50 years on, the Memorial Council is still predominantly the province of middle-aged to elderly men, a good proportion of whom have been or still are senior military officers.

The Memorial Council is no more male than its counterpart organisations in other jurisdictions in Australia or overseas and possibly not much older on average. But the Council is by far the most militarised of the bodies we have looked at (with the exception of the Victorian Shrine but only if we count the ceremonial Governors there). Indeed, a detached observer looking at the current Council membership (or, for that matter, its membership at any time over the last 75 years), without knowing who it belonged to, might take it to be the Board of a Naval, Army and Air Force Club rather than of a national war memorial, albeit a club that was doing its best to be welcoming to female members and the younger generation and to keep up its links with military history buffs, particularly philanthropic ones.

Then, the Memorial’s portfolio location under Veterans’ Affairs (and nominally under the wing of Defence) gives it a special status. As was intended by those, led by the RSL, who supported the portfolio move in 1984, location separate from other cultural institutions frees the Council from the need to balance the Memorial’s interests against directly competing portfolio claims, as might be the case in the Canadian model (one war museum within a cluster of cultural institutions), the British model (widely disparate appointing authorities leading to dispersed loyalties) and the New Zealand model (direct ministerial control).

Having lots of brass around the Council table does not necessarily mean they will run the Memorial, of course, despite the words of section 9 of the Memorial’s Act (‘conduct and control’, determination of policy). The Council only meets four times a year while the Director and his officers are on the job the year round. An activist director and a quiescent council will strike a different power balance compared with a mild-mannered director and a feisty council.

The Council also has committees, whose role we have not considered here, but which meet in between meetings of the Council. The Council may simply rubber stamp decisions of committees whose work has been dominated by the Director and his staff. During 2014-15 the Council had just three committees, on Finance, Audit and Compliance, the remuneration of the Director, and the membership of the Council. This last committee provides advice to the Minister through the Chair of the Council and thus bears some responsibility for the ‘look and feel’ of the Council’s membership.

There are also long-term volunteer guides and a Friends of the Memorial group who have exercised influence in the distant (and less distant) past, frustrating attempts by directors to change the way things have always been done.[6] The RSL has always had an inside track into the Memorial, too, most recently when Admiral Doolan was simultaneously Chairman of the Council and National President of the RSL, which had the potential to create conflicts of interest.

Council meetings might also witness interesting situations to do with deference and hierarchy. How does it affect decision-making and politics when the director was not all that long ago the ministerial boss of some of the members? Then, while the appointment of younger members to the Council is to be welcomed, how will a former Wing Commander and a former Corporal, used to chains of command, fare in discussions with all those two- and three-star officers, retired and serving?

Mutual reinforcement

Definitively answering the question about who really runs the Australian War Memorial would require leading more evidence than we have attempted here. We would really need to be a fly on the wall alongside all that brass in Council meetings and in other environments at the Memorial. (There is scope here for a television documentary.) Yet, the ‘who decides?’ question certainly needs to be asked of an organisation that claims it has a unique hold on the nation’s soul, let alone on a decent chunk of its money.

Canadian High Commissioner McArdle presents a uniform to AWM Trustee AGW Keys, 1976 (AWM 043712)

Canadian High Commissioner McArdle presents a uniform to AWM Trustee AGW Keys, 1976 (AWM 043712)

Controlling bodies clearly have the ability to set the style of an organisation, even if they are not involved in minutiae. The ability of the Memorial to continue much as it has done for the last 75 years as a monument to how well Australians have fought and died is influenced as much by the composition of the Council as it is by the Council’s narrow interpretation of the Memorial’s Act. Together these influences encourage the Memorial to continue to focus mainly on the exploits of Australians in uniform rather than on the wider impacts of war.

The spectre of Charles Bean helps in this regard. He – or a bowdlerised version of him – has been for decades a talisman or mascot for the received view of commemoration. ‘I don’t think Dr Bean would approve of what is happening here’, said the founding president of the Memorial’s volunteer guides in 1983 of changes being promoted by then director Jim Flemming.[7] Bean may have been called up also by the Vietnam veteran who opposed director Nelson’s plans to project images onto the wall of the Memorial. This gentleman feared the Memorial was ‘in danger of going down the historical theme park road’. On the other hand, Bean is still regularly – if selectively – quoted in Memorial publications, in speeches by its spokespersons and on the Memorial’s walls.[8]

Despite Bean’s conservative influence, his work provides a clue as to how the Memorial and its Council might change. Bean lauded volunteer forces, men and women who came, served for a while, then, if they survived, returned to their families changed. Why then is the legacy of those volunteers in those great wars, the great majority of our war dead and damaged, carried in the Council of the War Memorial by permanent, professional military officers and by retired men (and the occasional woman) who have served life terms (or at least many years) in the services?

The majority of the Council looks nothing like Australia then – or now. The Anzac tradition carried by the military members, the selective legacy of Bean, the sentimental version of remembrance favoured by the Council’s authors and aficionados, and the ambitions of the Memorial’s senior management will tend to reinforce each other. There is a grave risk that the contestability which should characterise a nation’s history will stop at the door of the Memorial’s Council room.

A modest proposal

A reform that an incoming government should consider would be to amend the Australian War Memorial Act to allow for Council vacancies to be filled through public advertisement. Positions in the mass armies, air forces and navies of the past were filled by recruitment drives boosted by patriotic advertising; positions on the body which determines how these men and women are remembered could also be filled by advertising and application.

The Minister might continue to appoint the Chair of the Council, some ex officio military positions might be retained (though they might not necessarily be filled by the service chiefs), but the other positions could be filled by qualified and interested members of the community, chosen by the Minister, taking account of the advice of sitting Council members, senior staff of the Memorial and respected citizens. The members appointed might have a background in, for example, the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia, Legacy, the Medical Association for Prevention of War, the Red Cross, Soldier On, the United Nations Association, and university history departments. There might even be some elected positions. An institution which claims to tell its nation’s story should surely be open to having Council members democratically elected by, from and for the nation.

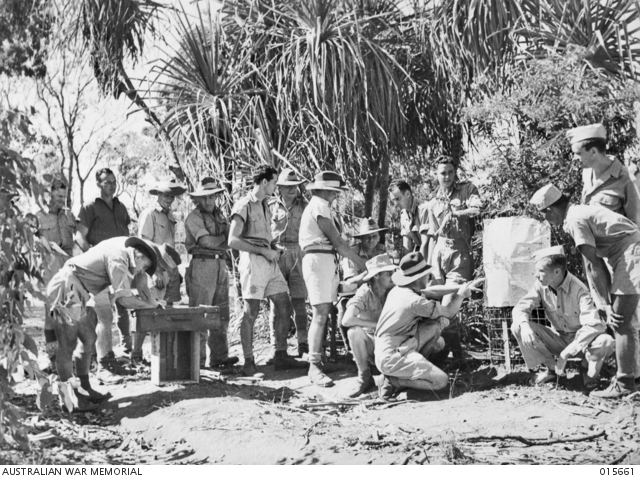

Australian soldiers in NW Australia vote in the federal election, 1943 (AWM 015661)

Australian soldiers in NW Australia vote in the federal election, 1943 (AWM 015661)

Australians enlisted for our major wars in great numbers. Some of them became officers. A handful of them became senior officers. Decades on, too much of the control of our national war memorial has devolved to the senior officer cadre and a supporting cast of the Australian version of ‘the great and the good’. The people should be allowed to take back this role. The remembrance of war – and, more importantly, the prospect of peace – are too important to be left to those who have made a profession out of military activity or a hobby out of military history. These matters affect all of us and our future, not just those who try to keep the Anzac flame burning in pretty much the same way as it has for the last century.

The War Memorial Council as presently composed is an anachronism. It stands in the way of significant change in the way we commemorate war and hope for a peaceful future. A Council which was more representative of the range of Australian experience of war – and of Australians – would help the Memorial tell a more rounded story, a story not just of daring and death in uniform but of the widespread and lasting effects of war on individuals, families (especially women and children) and communities. The story not just of what Australians have done in war but of what war has done to Australia and Australians – and what it should never do again.

Endnotes

[1] Michael McKernan, Here is Their Spirit: A History of the Australian War Memorial 1917-1990, University of Queensland Press and Australian War Memorial, St Lucia, 1991, p. 228.

[2] When Chief of Army, and thus ex officio a member of the War Memorial Council, Lieutenant General David Morrison, told soldiers returning from Afghanistan that ‘you have added you own distinctive chapter to the legend of the ANZACs. You have joined that long, loping column stretching back in memory’s eye through the mist of time, of those who have worn the slouch hat and Rising Sun badge abroad in the service of their country.’

[3] McKernan, pp. 328-37.

[4] Searching the Memorial’s website shows that the Minutes of a Council meeting and a Council Committee meeting in August 2000 are available in the Memorial’s collection.

[5] McKernan, pp. 242-43.

[6] See below note 7.

[7] McKernan, p. 311.

[8] Biographies of Bean, like those by Coulthart and Rees, reveal the complexity of the man, the war correspondent, the diarist and the war historian.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.