‘Rowing on after the Great War: the origins of the King’s Cup’, Honest History, 8 July 2019

Lucas Jordan reviews Bruce Coe’s Pulling Through: The Story of the King’s Cup

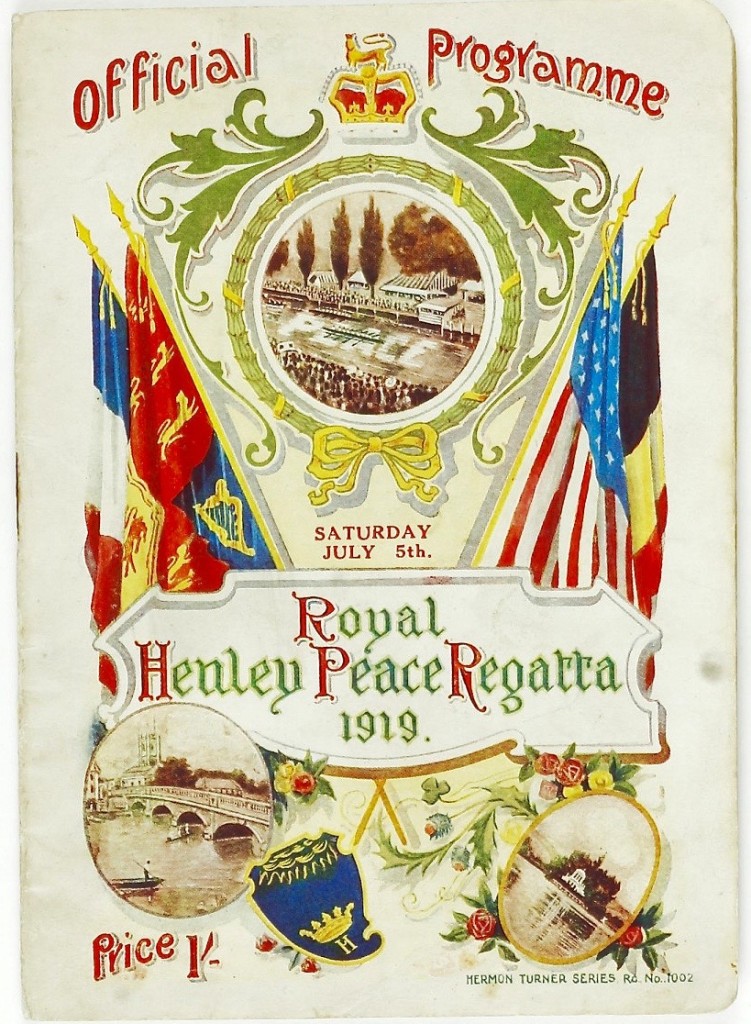

On Saturday, 5 July 1919, an eight-man rowing crew of the Australian Imperial Force won the King’s Cup from the famous blue blades of the Oxford University Boat Club at the Henley Peace Regatta. The Peace Regatta marked the end of the First World War, but the strain of that conflict was clear on the bodies and faces in the boats and the spectators on the banks of the famous River Thames. Pulling Through: The Story of the King’s Cup, by sports historian Bruce Coe, commemorates the centenary of the King’s Cup and underlines its legacy in Australian rowing.

In the introduction to the book, Andrew Guerin, Chair of the Australian King’s Cup Centenary Committee, writes that the King’s Cup is ‘more than a race’. The title Pulling Through refers not just to the oarsmen on the water but also to the drama involving the contest over the legacy of the trophy. Originally, the Australian War Museum Committee (the forerunner of the Australian War Memorial) were authorised to keep the trophy as a war relic for display, while the rowers and their backers wanted to see it honoured as an inter-state, perpetual trophy contested each year.

In the introduction to the book, Andrew Guerin, Chair of the Australian King’s Cup Centenary Committee, writes that the King’s Cup is ‘more than a race’. The title Pulling Through refers not just to the oarsmen on the water but also to the drama involving the contest over the legacy of the trophy. Originally, the Australian War Museum Committee (the forerunner of the Australian War Memorial) were authorised to keep the trophy as a war relic for display, while the rowers and their backers wanted to see it honoured as an inter-state, perpetual trophy contested each year.

At the heart of this short history is the outcome of the debate about how best to commemorate the 5000 Australian rowers who enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force. The role of sport in the repatriation of the Australian Imperial Force in 1919 is what makes Pulling Through distinguishable in the plethora of books marking the centenary of the Australian part in the First World War.

In 1919, the English rowing establishment decided to temporarily set aside the Henley Royal Regatta and replace it with a one-off event, the Royal Henley Peace Regatta, a rowing event specifically for former service men of the Allied imperial and expeditionary forces and the famous light and dark blues of the Cambridge and Oxford rowing clubs. Bruce Coe begins by describing the formation of the Australian Imperial Force Sports Control Board (SCB), which played a leading part in the repatriation and welfare of Australian soldiers for whom the war was over, yet the prospect of a swift return to Australia was beyond possibility.

By March 1919, the SCB had identified first and second crews to compete in the VIII, IV and II categories at the Peace Regatta. Stephen Fairbairn was selected as coach. He was ‘a brilliant and innovative rowing coach’ with experience at Cambridge and the Thames and London Rowing Clubs before the war. Ultimately, Norman Marshall replaced Fairbairn and went on to coach the AIF VIIIs to victory. Readers of military history will be aware of Marshall’s record as a battalion commander and might argue that he still awaits his biographer.

Sadly, the book generally lacks penetrating studies of the character and war experience of the winning crew or the other Australians who rowed in the Peace Regatta. Perhaps Coe simply could not find the biographical material in the sources. The personal service records of the winning crew, held by the National Archives of Australia, reveals big wars were experienced at Gallipoli and the Western Front by many men who later became Peace Regatta crew members. For example, there was Arthur Valentine Scott, the number four, who had been a locomotive foreman before enlisting. Scott’s mother died while he was on active service, and his brother was killed in action. Faced with such family tragedy, Scott refused to go into the front line because he wanted to get to England to clear up his dead brother’s personal effects. He was court martialled and charged with ‘wilful disobedience of a lawful command given personally by his superior officer.’

Such life-affirming stories are not included in Coe’s account. Harry Hauenstein, ‘a magnificent oar with a perfect blade and finish’, earned the Military Medal for ‘repeatedly’ going into No Man’s Land at Mouquet Farm, near Pozieres, to rescue wounded men under intense fire. These interesting and character-rich stories are not included, their lack suggesting that the author might have taken the reader on a deeper journey. Regrettably, the result is that most of the Australian rowers mentioned in Pulling Through remain shadowy figures throughout the book.

On the other hand, Coe relies heavily on newspaper reports and the odd letter to add descriptive power and interest to his narrative. He draws on the astute observations of the rowing reporters of papers such as the Daily Telegraph, The Times and the Sporting Life. These contemporary accounts paint a picture in journalistic prose of the strengths and weaknesses of the rival teams.

Unfortunately, the book is a clunky read, lacking a clear authorial voice prepared to analyse the sources. Names of rowers, dates of events and results are recorded ad infinitum but without that great hook which comes when history and narrative combine to build tension and develop central characters. Nevertheless, Coe’s eye for humour and storytelling sometimes rises above simple rehashing of excerpts from primary sources. The moment of victory is the most vivid and enthusiastically penned in the book. ‘Genteel Henley had never before seen such antics, which at times would have been bordering on raucous.’

Slattery Media Group produced the book for Andrew Guerin, with sponsorship from members of the Australian rowing community. It is a very short book of 175 pages including appendices, notes and index. It serves as something of an honour roll, illustrated with many images of the Peace Regatta, held by the University of Melbourne and other sources, a comprehensive list of rowers, coaches and results.

Peace Regatta program (Hear the Boat Sing)

Peace Regatta program (Hear the Boat Sing)

The winning of the King’s Cup is the climax of the book but Coe’s chapter, ‘Winning the King’s Cup – Again!’, describes how a few passionate rowers secured the cup’s legacy as a perpetual inter-state competition. The Australian War Museum Committee (and the Commonwealth Government) wanted to keep the King’s Cup as a ‘war trophy’, arguing that more Australians would see it and appreciate the story if it travelled the country as an object in an exhibition.

The Australian soldier-rowers saw it differently, however. As Bruce Coe memorably puts it, ‘Having survived the war and having won the trophy in good competition, the crew was in no mood to allow the AWM to have its way’. So, ‘the second battle to win the King’s Cup’ went all the way up to King George V. Bruce Coe finishes the book with this intriguing story. Thanks to the King’s approval, the King’s Cup continues to hold ‘a special place in Australian rowing’.

* Dr Lucas Jordan is the author of Stealth Raiders: A Few Daring Men in 1918, Vintage, Sydney, 2017.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.