Peter Stanley takes over the Jauncey pen from David Stephens.

I’m in Kolkata to deliver the keynote address at a conference, ‘Re-newing the military history of colonial India’, held at Jadavpur University, one of the most prestigious educational institutions in West Bengal. The conference is called ‘re-newing’ but actually it’s the first time that such a conference has been held in India – ever, it seems.

What a contrast to Australia, where military history is an accepted, familiar, even unduly dominant presence in our national history. In India, military history is associated either with the Raj (and therefore an alien presence) or with continuing conflicts with India’s neighbours and so pre-1947 history is irrelevant. And what military records that exist are either locked up in the possession of the Defence Force or almost as inaccessible in the hard-to-get-into (and almost as hard to use) National Archives, in distant New Delhi. The ready access to military records that we enjoy in Australia – from official war diaries to Dear-Aunty-Joan letters by ordinary soldiers – is a remote dream to Indians, whether they are scholars or those few interested in the unfashionable military past.

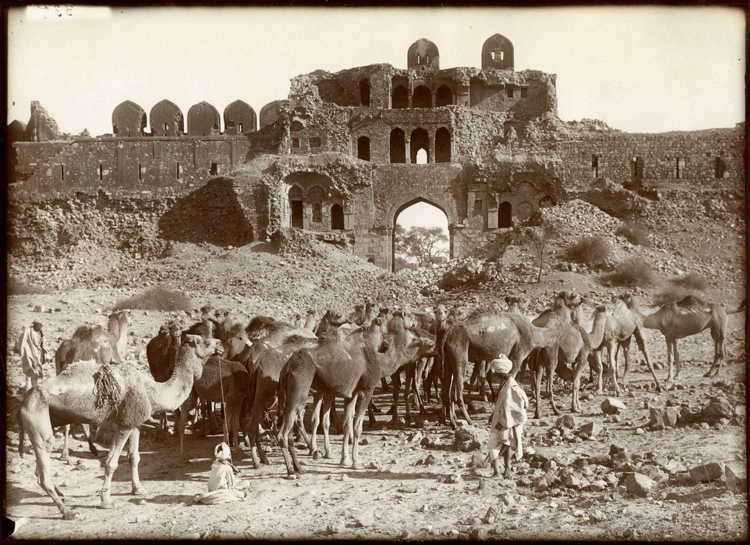

The walls of Old Delhi c. 1907 (source: National Archives UK COPY 1/507/177/Flickr Commons; photo: Herbert Ponting)

Yet Indians are doing military history, attempting to arouse interest in the military experience of Indians in war and in the effects of that war on the peoples of the sub-continent – undivided India as it was. They include Rana Chhina, a genial but very effective former squadron leader, who heads the quasi-official Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research in New Delhi. Rana has virtually single-handedly created a collaborative project involving scholars from India and overseas who are working on aspects of India’s part in the Great War and who will produce books, papers, articles and films that will contribute more to raising awareness than has occurred since … well, since 1918.

At the opposite end of the country, a young but astonishingly energetic and productive academic, Professor Kaushik Roy, has convened the Jadavpur conference and has also assembled a team of researchers, from Britain, Europe and Australia (me) and, more importantly, from India, including many aspiring scholars. They are also pursuing India’s military history on a broad front, from the experience of Indian patients in military hospitals to the ‘counter-insurgency’ operations on the North-West Frontier, all working in the face of shortages of everything from primary sources (many inaccessible) to (especially) research funding.

For an Australian, the experience is humbling. Coming from a country which values – perhaps over-values – its military history, with an abundance of records of all kinds, freely available, with researchers of all kinds, many well-funded, it is a sharp reminder of our good fortune to see and hear of the problems confronted by colleagues in India and to see how they face them with patience and ingenuity.

Speaking at the Jadavpur conference, I asked, ‘Who owns India’s military history?’ It could be claimed by many – by sectional religious, linguistic or religious interests. Can non-Sikhs truly do Sikh history? Who will offer a critique of Shivaji, the Maharashtran hero of whom Maharashtrans are so proud? Does the subject belong to the Defence Force (which hugs its records to itself) or only to those who have served? Does it belong to the contending sectors familiar from Australia’s military history, the operational historians or the social historians who pursue history so differently?

Statue of Shivaji, Pune, India. Shivaji is reputed to have defeated the invading Mughals and was also the first warlord to take up arms against the British (source: Flickr Commons; photo: Shankar S)

To explore the issue, I took a leaf from a classic of Australia’s literature of war; I refer to Norman Lindsay’s children’s book, The Magic Pudding, published in 1918. As well as producing some of the most vicious and hate-filled war propaganda Australia has ever seen, Lindsay also wrote, at exactly the same time, a children’s book of enduring charm.

As Australians don’t need reminding – but as Indians were amused to learn – ‘the pudden’ – Albert – is a surly and unpleasant character. But in that he is a magic pudding he is a generous figure, transforming himself into any pudding desired and inviting all to share him as a cut-and-come-again dish. That, I suggested, was the answer to the question, ‘Who owns India’s military history?’ India’s military history is a magic pudding, able to be consumed over and over in any style we desire; able to satisfy all tastes at once; inexhaustible (provided the records are available!)

Cover of The Magic Pudding, now available as an audio book from Angus & Robertson

What works for India will work for us. The history of Australia’s wars is likewise open to be interpreted, explained and represented in many ways, all legitimate as long as we respect the authenticity of the evidence and treat the past honestly. As I sit here, chewing my Kolkata chota hazri – my little breakfast of rubbery omelette and crunchy toast with fluorescent jam – I can reflect on Australia’s good fortune and on India’s prospects of also being able to comprehend its military history.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.