‘Some extracts from Honest History’s Alternative Guide to the Australian War Memorial, Second edition, June 2017’, Honest History, 25 July 2017 updated

We have produced the second edition of Honest History’s Alternative Guide to the Australian War Memorial. The second edition is about 20 per cent longer than the first, with more attention being paid to World War II and later conflicts. It also takes account of changes in the Memorial’s temporary exhibitions (notably the arrival of the For country, For Nation exhibition – which closed in Canberra in September 2017 but is to go on tour nationally) and the new permanent exhibition on the Holocaust. Following are some extracts from the second edition.

The first edition of the Alternative Guide was posted on the Honest History website on Anzac Day 2016. Over the next 14 months it was downloaded more than 2000 times by students, teachers and members of the general public.

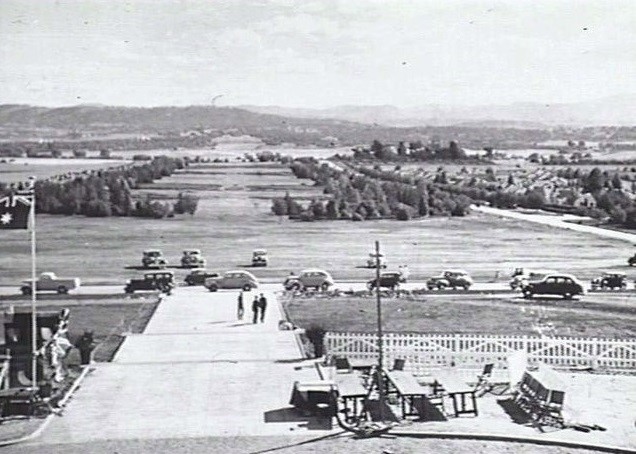

View from the Australian War Memorial steps, opening day, 11 November 1941 (AWM 130300/RS Conrow)

View from the Australian War Memorial steps, opening day, 11 November 1941 (AWM 130300/RS Conrow)

_______________________________

The themes of the Alternative Guide

Reading the Memorial

The Australian War Memorial is a complex ‘site of memory’ and it can be read in different ways, many of which may be legitimate or justifiable. The Alternative Guide recognises the ‘readings’ the Memorial offers but then offers alternative readings.

…

This Alternative Guide wants to help change public expectations of the Memorial. Look, for example, at the definition of ‘Australian military history’ in section 3 of the Memorial’s Act: ‘the history of: (a) wars and warlike operations in which Australians have been on active service, including the events leading up to, and the aftermath of, such wars and warlike operations; and (b) the Defence Force’.

Reading this, you might think that ‘the history of … wars’ would include something about why these wars occurred, the experience of the people Australians fought against (as well as of Australians), and the effects of war on Australia and other countries. Yet the Memorial’s ‘Mission’, as set out in its Corporate Plan, is a lot narrower than the words in the Act. It says this: ‘To assist Australians to remember, interpret, and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring impact on Australian society’ (emphasis added).

Does this emphasis on ‘the Australian experience of war’ and its ‘impact on Australian society’ allow the Memorial to take a parochial, Australia-centric view, ignoring the rest of the world? Should the Memorial focus more broadly? You could keep these key questions in mind during your visit. (None of them imply any disrespect to Australians who went to war.)

Complexity

‘Official’ interpretations of history need to be challenged and corrected, not just because they are unduly dominant – due to their endorsement by powerful interests – but to offer alternative readings. The discipline of history is all about a contest between interpretations. History – ‘what happened’ – is not a single narrative. Nor is history, the discipline. The more interpretations that contest with each other, the more complex history becomes. That should be welcomed.

Context

A key theme of the Alternative Guide is ‘context’. Are there ‘silences’ in the Memorial’s galleries which need to be filled? We suggested above that the Memorial presents an Australia-centric or parochial view of the wars in which Australia has been involved. The Guide will point to where the Memorial could consider the impacts of war on people other than Australians.

…

The Memorial also emphasises the deeds of men and women in uniform. You could ask whether this emphasis is at the cost of describing what was happening on the home front, to women, children – and men. These people were the majority of the population, the ones who did not go to war. For example, Joan Beaumont in Broken Nation points out that, during World War I in Australia, ‘[a]mong men aged 18 to 60, nearly 70 per cent did not enlist’. So the Guide suggests where there is room to look at what was happening at home.

…

Honesty (and evidence)

The final key theme of the Alternative Guide is ‘honesty’. The Honest History coalition deliberately included the word ‘honest’ in its title to emphasise the importance of honesty in the way all of us should approach history. History means interpretation; ‘honest history’ is interpretation robustly supported by evidence.

But honest history is also about telling the full story, not holding evidence back, not sanitising. Look for places where the Memorial presents (or fails to present) evidence in a way that produces sanitised or misleading or partial stories. (Here we mean ‘partial’ in both senses – not telling the whole story and favouring just one side of the story.)

…

What are you supposed to feel when visiting the Memorial, when looking at an object or a diorama or an exhibit? Do you feel you are being manipulated? Is an object or display offering you historical evidence or just giving you a warm and fuzzy feeling or making you feel sad or making you feel proud to be an Australian? Should the Memorial make you think as well as make you feel?

…

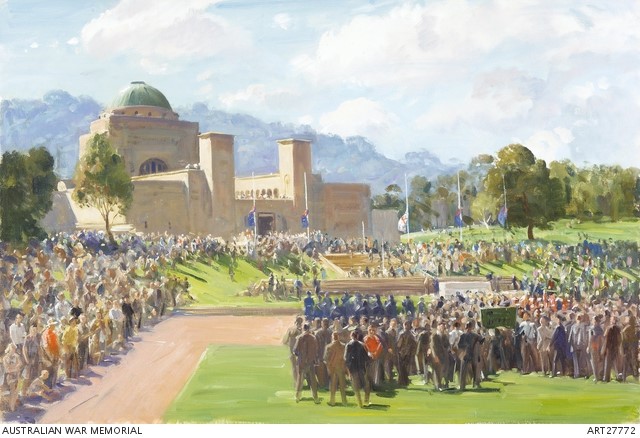

Anzac Day ceremony, Australian War Memorial, 1971 (AWM ART27772/William Dargie)

Anzac Day ceremony, Australian War Memorial, 1971 (AWM ART27772/William Dargie)

______________________________

Section 5: The other galleries

World War II

The Holocaust: Witnesses and Survivors

This is a new (November 2016) exhibition at the Memorial. It looks at the Holocaust through the eyes of survivors who came to Australia and through the work of an official war artist, Alan Moore.

Look at the sketches by the survivor, Bernard Slawik. Why do you think he worked on and reworked them throughout his life?

Is it possible to not serve in the military forces yet be deeply affected by war? Would you like to see the Memorial show more of the impact of wars on ordinary people, not necessarily Australians, or should the Memorial be mainly about Australians in uniform?

Some Australians objected to the Memorial opening this exhibition. Why?

Sources: Australian War Memorial (including opening speech) Canberra Times; Stanley (review of the exhibition)

…

1940-41 Victory and defeat

In this area of the Memorial there are a number of vehicles displayed – trucks, a motor cycle and side-car, a small tank.

In the Aircraft Hall, to the rear of the Memorial, there are aeroplanes, and a sign on the wall, ‘Big Things’.

What do large objects like this tell us about how men and women experience war?

1942 Turning point

‘Work, Fight or Perish.’ Watch the speech by Prime Minister Curtin in Sydney, which is part of a newsreel called ‘All Must Serve’. What do you think of the prime minister’s speech-making style? Would it have an impact today?

What were ‘Liberty Loans’?

Do you think it is true to say that Prime Minister Curtin gave his life for the war effort?

Nearby, there is a poster ‘He’s Coming South’. What emotions does the poster try to provoke among people who see it?

Sources: Australian Dictionary of Biography; John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library

Kokoda Trail

A little further on there is a mock-up of a section of the Kokoda Trail or Kokoda Track. Why is Kokoda seen as important, even today?

Many people today walk the Kokoda Trail. Why?

What do you think of the argument that Kokoda is more important to Australians than Gallipoli? Does it matter whether one battle in one war is more important than another battle in another war? Why?

What did Prime Minister Keating do at Kokoda in 1992. Why?

Sources: Cooper (different views of Kokoda); O’Lincoln (Kokoda or Gallipoli?); Watson (Keating)

…

1943-44 Australian Comforts Fund

Watch the newsreel in the Australian Comforts Fund exhibition. What does it tell you about attitudes to women during the war?

Were women who did jobs normally done by men paid the same wages as men had been?

1944-45 Final campaigns

Find the exhibit about the Bougainville campaign 1944-45, a campaign which, we are told, ‘did nothing to end the war one second sooner’. If you had fought in this campaign and had been told this after the war, how would you have felt?

Is it sometimes difficult to make a connection between the actions of individual soldiers or groups of soldiers in battle and ultimate outcomes?

…

Victory in Europe: D-Day

One million Allied troops landed in Normandy in a month, 150 000 on the first day, the largest sea-borne invasion in history, much bigger than Gallipoli.

Does an invasion have to involve massive numbers over a short time or can it start small and take much longer? Have there been any invasions of Australia?

Pacific war ends

Find Australian General Blamey’s statement to Japanese General Teshima at Morotai, September 1945. The statement commences, ‘I do not recognise you as an honourable and gallant foe …’

Why would Blamey have said that? Was it fair?

Should our attitudes to former enemies today be affected by their actions during past wars?

After the war

Above the little plywood crosses, there is a small display depicting the early post-war years. It covers the Korean War, the development of new suburbs, the growth of prosperity, industrial development, and immigration.

Would you like to know more about what happened after the war, particularly whether things were better after the war than they were before, and why?

Can you see anything in the Memorial about the lives after World War II of the men and women who returned home physically and mentally damaged from the war?

Read more of Honest History’s Alternative Guide to the Australian War Memorial (second edition) and download it.

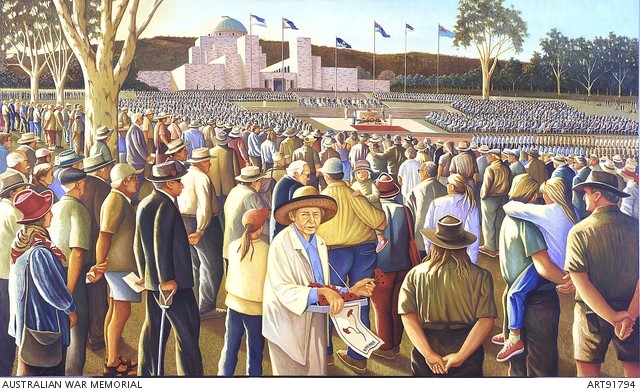

60th anniversary of opening of the Australian War Memorial, Remembrance Day, 2001 (AWM ART91794/Bob Marchant)

60th anniversary of opening of the Australian War Memorial, Remembrance Day, 2001 (AWM ART91794/Bob Marchant)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.