‘Highlights reel: ‘and the war came’, Honest History, 4 August 2014

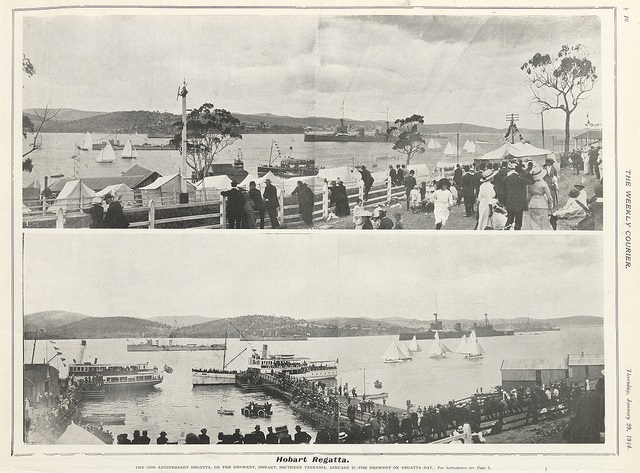

Hobart Regatta photos from the Weekly Courier newspaper, January 1914 (Flickr Commons/Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)

Hobart Regatta photos from the Weekly Courier newspaper, January 1914 (Flickr Commons/Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)This highlights reel takes extracts from Australian press editorials and other published material in the few days leading up to the start of the Great War.

It gives an idea of the atmosphere at the time, the speed with which matters came to a head, the uncertainty about what was to come next, and the dual culture of Australia at the time, as a new nation within a controlling Empire.

Britain was dealing also with serious unrest in Northern Ireland (Ulster).

The Hobart Mercury‘s editorial on Monday, 27 July 1914, was pessimistic but reasonably prescient.

Once again Europe is threatened with war [there had been two wars in the Balkans since 1908]; indeed, it may be that even now Austria and Servia have entered upon a conflict. If it were merely a question of Austria punishing Servia for refusing to take action against subjects of the latter who plotted and planned the assassination of the Archduke there would be very little in it. But there is the feeling that this is merely a pretence, and that actually the war is another step towards the establishment of Teutonic influence in the Balkan States, and, therefore, a blow to the Slav prestige …

There is no reason to doubt that the Kaiser is ready once again to support the action of Austria [as he did when Austria annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908], and the question is whether the other Powers will stand by and allow these two allies to work their will. Presumably the Ulster crisis, with the threat of civil war, has had its influence. France may be ready to support Russia in a vigorous protest against Austrian aggression in the Balkans, but to make reasonably certain of success the backing of Great Britain, at her strongest, is required.

The fact that the British Government is face to face with the most serious crisis which has occurred in many generations [Ulster], and that even the King has openly admitted the possibility of civil war, must tend to give confidence to Austria. But, should war really threaten, the British family will postpone its domestic quarrels, as it has done before, and those who look for weakness are likely to find strength and loyalty.

On Tuesday, 28 July, the Melbourne Argus ran a collection of items drawn from cables dated 26 and 27 July. Their tone was cautiously hopeful.

FIGHTING ON THE DANUBE; RUSSIA USING INFLUENCE FOR PEACE; HOPEFUL REPORT FROM ST. PETERSBURG

LONDON, July 27, 2.45 p.m.

The only developments during the past 24 hours in the Austro-Servian dispute have been in the direction of either avoiding the possibility of conflict altogether or at least of localising it. The British Government has suggested that Germany, France, Great Britain, and Italy should mediate in the dispute.

There is a more hopeful feeling in Paris and St. Petersburg, following a long interview which the Russian Foreign Minister (M. Sazonoff) has had with the Austrian Ambassador to Russia. M. Sazonoff has made suggestions which he deems will satisfy Austria, while safeguarding Servia’s sovereignty. At the same time he has informed the German Ambassador at St. Petersburg that Russia will not be able to remain indifferent if Servia is invaded.

It is semi-officially announced in Berlin that Germany has approached the French, Russian, British, and other Governments, suggesting that the conflict be localised. When Austria, it appears, informed Germany of the facts regarding the anti-Austrian propaganda in Servia, Germany agreed that the position was unendurable, but did not see Austria’s ultimatum

English newspapers consider that Austria’s ultimatum was unduly humiliating, though Austria was justified in demanding the suppression of the anti-Austrian propaganda. Servia’s reply, they say, shows that she is not unprepared to make reparation, and Austria, therefore, should exercise forbearance in the case of a so much smaller power.

The next day, however, Wednesday, 29 July, the Adelaide Advertiser seemed to be picking up some hints from London that matters were about to come to a head.

It is, perhaps, an inevitable result of Great Britain’s “splendid isolation” that the aims of her foreign policy should be so widely misunderstood … Because a British Minister has stated that his country is unfettered by obligations to a single Continental Power, it is assumed that the Power or Powers who believe themselves to be the military masters of Europe are to be free to ride roughshod over all others.

Never was there a mistake more fatal, as the latest utterance of Sir Edward Grey [British Foreign Secretary] shows abundantly enough. While the quarrel is restricted to Austria and Servia there will be no intervention, but “the moment another Power enters the struggle,” adds the Foreign Secretary, “the situation would become different, for it would then be a question of the peace of Europe.”

As an exposition of British foreign policy nothing could be more lucid; nor is it a foreign policy devised solely for the present emergency. It has never been the desire of Great Britain to meddle with the affairs of other nations, but neither for Great Britain any more than for other Powers has there been each a thing as standing aloof from Continental affairs. From time immemorial her policy has been twofold – first to guard her own, and, secondly, arising from the first requirement, to hold the balance even between the Continental forces …

With a world-wide Empire to defend, Great Britain has as much to lose as a Continental Power from the establishment of a European dictatorship …

So on the present occasion, while Great Britain is bound by no existing treaty to make war in conjunction with any one set of Powers against another, Sir Edward Grey has said enough to show that she will be no unconcerned spectator of what the next few weeks or months may produce on the Continent.

The Sydney Morning Herald of Thursday, 30 July, was mostly concerned about what a European war would mean for Australian exports.

Some people in this part of the world, after reading this morning’s cablegrams, with their news of war declared by Austria against Servia, and the demoralisation of the world’s markets, will think that, after all, it does not much matter. The trouble is far away. If the conflict does not spread, why should we worry? And even if there should be a great European war, with the Powers engaged in hammering each other to pieces, why should Australia be unnecessarily distressed?

We are bound to be outside of the area of conflict, in any case, and when peace is finally declared the Commonwealth will still be facing the Pacific, and New South Wales will continue to draw wealth from a world that will still want wool, wheat, gold, silver, and the industrial metals.

But it will not do. This continent, for better or worse, is an integral part of the civilised world to-day; and a war which shakes Europe will assuredly shock Australia …

While Britain remains outside the circle of conflict all is well, and as long as the British fleet is supreme, even if the mother country has to take sides, there need be no fear. But peace is essential to our continued well-being. That is the point we would press home. Our trade cannot keep its volume unless our customers in Europe, where the bulk of our oversea business is done, are as open to buy as we are to sell.

On Friday, 31 July, the Brisbane Courier was reporting (dateline Wednesday) that the threatened British election was to be put off, as much because of the Ulster crisis as the impending war. The headlines on the same page, however (dateline Thursday), ran like this: ‘The die is cast; Only a miracle can prevent war; Belgrade bombarded and occupied; Departure of British First Fleet; Stirring scenes; Active Russian mobilisation; Regarded by Germany as intensely serious; Diplomatic intercourse between Russia and Austria suspended; Preparations in France’. In the House of Commons, the British prime minister, Asquith, said the situation was extremely grave but his government ‘was doing everything to circumscribe the area of the conflict’.

The Melbourne Argus of Saturday, 1 August, thought matters in Europe were important enough for it to insert, on its normal advertising only front page, the following teasers: ‘European crisis; Russians mobilising; Germany demands cessation; Insists on early reply; Excitement in capitals’. Most of the edition seems to have been ‘prepared earlier’ for weekend reading, however, with items about the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn, the Royal Family, the civilising British, Baby Sunday in the churches and GE Morrison in China.

Pages 17-20, however, were largely war news, with a large graphic and lengthy text about the disposition of the British Fleet, plus a map of the North Sea. There were eight headlines, with ‘Threatened European war’ leading the way, and many small articles, dated 30 and 31 July, carrying news from European capitals. The Irish Home Rule issue had been deferred in the House of Commons by the agreement of all parties, who recognised that more pressing issues had intervened.

In the streets of Melbourne, people felt there was ‘about an even chance’ of a European war and that what happened in Europe was ‘likely to have considerable influence’ on Australia. There was ‘optimism’ and ‘excitement’ but no alarm. In New Zealand, the members of Parliament rose in their seats and sang the National Anthem. The Argus editorial, though taking second billing to one about the Australian general election, was very grim:

The position in Europe has not greatly changed, according to the news published to day; but in times of crisis events move rapidly, and no one knows what a day or an hour may bring forth. Whether Great Britain will be called upon to fight seems, at the moment, to depend upon Germany … While there still is ground for hoping that Great Britain may not need to fight, it cannot be denied that the situation is extremely critical.

The federal election campaign was properly under way but the party leaders set out very similar positions on the war. Andrew Fisher at Colac:

Turn your eyes to the European situation, and give the kindest feelings towards the mother country at this time. I sincerely hope that international arbitration will avail before Europe is convulsed in the greatest war of any time. All, I am sure, will regret the critical position existing at the present time, and pray that a disastrous war may be averted. But should the worst happen after everything has been done that honour will permit, Australians will stand beside our own to help and defend her to our last man and our last shilling. (Loud applause.)

Joseph Cook at Hamilton:

The outlook is serious, and what is going to happen I do not know. I hope that reason will get the better of these passionate feelings that have been aroused, and that there may be peace without resort to the arbitrament of arms. We don’t know when this fire starts where this conflagration is going to end, and every effort will be made to check it.

In the meantime, we may feel sure that we have wise counsels at the seat of government in London, and I have the fullest confidence in Sir Edward Grey at this juncture, and whatever happens Australia is a part of the Empire right to the full.

Remember that when the Empire is at war, so is Australia at war. That being so, you will see how grave is the situation. So far as the defences go here and now in Australia I want to make it quite clear that all our resources in Australia are in the Empire and for the Empire, and for the preservation and the security of the Empire. (Loud cheers.)

In other news, Australasia (Australia and New Zealand) was getting the better of Germany in the Davis Cup.

On Sunday, 2 August, the Perth Daily News brought out a special edition, one page war, one page sport and general news. The headlines read: ‘Germany declares war on Russia! Appalling European situation; French army mobilising; Russia ready to strike; Italy standing neutral; Great Britain’s move unknown; Some sensational cablegrams; The Kaiser and the sword of war’.

In over 40 short items about war developments, however, there was very little about Australian reaction. The Cabinet was to meet to consider despatches from London, senior military officers were on call, there was talk of rehearsing mobilisation arrangements, and prime minister Cook had spoken about the need for Australia to be prepared and to be able to integrate its efforts with those of Great Britain. But ‘Melbourne news’ was that ‘[c]omparatively little interest is being shown here publicly with regard to the war’ although the outlook was felt to be ‘black’ and the lack of an announcement from London about British neutrality was regarded as ‘significant’.

The Perth Sunday Times agreed that the situation was ‘intensely critical’. The Sydney Sunday Times headlined ‘The blow falls’ and ‘World will be ablaze’. Its cartoon was captioned ‘And women must weep’ against a background of soldiers with fixed bayonets charging against cannons. Again, there was very little about Australian impacts; but it was a Sunday.

On Monday morning, 3 August, the Melbourne Argus summarised the position in one sentence. ‘With Germany’s declaration of war against Russia, the European conflict has undergone a startling change.’ The paper thought it was still possible that Britain, Italy and perhaps France might not be drawn into the conflict though it noted that prayers for peace had been offered in all the Melbourne churches. ‘Great Britain is not actually allied either to France or to Russia, but she is a party to the entente cordiale with both, and is practically an ally.’

As for Australia, an unsigned article put the view that, ‘If Great Britain became involved in the war, the time will have arrived for the display of a patriotism that knows no party’. The author quoted both Cook and Fisher from 31 July and went on that ‘[t]he hour has come for Australia to make a definite offer’, which should be bipartisan and consist of ships or men or both.

We are bound to the motherland by ties not so much of material interest as of kinship and of gratitude. For a century we have lived in freedom under Britain’s protection. We have appreciated our great good fortune quietly. Ours is not a flaunting patriotism, but it is perhaps all the more profound because it lacks that quality. We have never hung back when war has made its appeal.

The Argus reported remarks from Cook at Colac over the weekend: ‘if it is to be war, if the Armageddon is to come, then you and I shall be in it. (Loud applause.) It is no use to blink our obligation. If the old country is at war so are we. (Loud applause.) It is not even a matter of choice. but of international law.’ The paper also reported the scene in Melbourne on the Sunday. (A Trove search of all Australian newspapers for the 15 days 27 July to 10 August 1914 shows the word ‘Armageddon’ was used 152 times.)

In a very little time folk in the city were telephoning the momentous news [of Germany’s declaration] to relatives and friends in the suburbs, and the result was an influx of people into the city from all directions and by whatever means of locomotion proved most convenient. By midday large crowds had gathered outside the daily newspaper offices [where regular bulletins were posted as cables arrived from Europe] and about the principal street corners. Melbourne received the news calmly and seriously. When the crowds were at their greatest numerical strength there was noticeable a gravity which told eloquently how the tidings were affecting the community.

On Tuesday, 4 August, the Sydney Morning Herald‘s editorialist seemed to recognise that the balance had tipped decisively towards the involvement of Britain and the Empire.

While there is hope as long as Great Britain is not reported as actually drawn into the circle of hostilities in Europe, it would be foolish to deny that the news up to date is cumulatively serious. Everything seems to point to the mother country being actively engaged as a combatant with Russia and France against Germany and Austria. There is the fact, no doubt, that our cablegrams do not contain any word of a declaration of war on the part of Great Britain. The Powers are pictured as waiting breathlessly for her decision …

If in some happy way Mr. Asquith has been able to guard Britain’s honour while keeping her out of the area of conflict, no part of the Empire will rejoice more heartily than Australia. But if peace is to be bought by surrender of principle, by the abandonment of friends, and has been preserved through fears of the consequences of an awful conflict, no people will sorrow and suffer more than we shall. Our place is with the mother country for good or ill.

The Cook Government had decided that Australia would place its fleet at the disposal of the Admiralty and offer an expeditionary force of 20 000 men. (The cable arrived in Whitehall before Britain had finally decided its position. (1)) Canada had pledged 30 000. New Zealand had offered a force, as well.

Meanwhile, at the military grassroots, preparations were under way. Warships were ready to sail at a moment’s notice. Forts and searchlights were manned. There was much scurrying at military barracks. Guards were posted at key points, such as Prospect Reservoir, a practice exercise commenced on the Hawkesbury and local defence plans were reviewed. Ambulancemen, nurses, doctors and former soldiers were alerted. At Cockatoo Island dock, while the talk was of war, ‘[t]here was no trace of anxiety and, were it not for the signs all round they might have been engaged preparing for a picnic’.

Cockatoo Island staff, Sydney, December 1914 (Flickr Commons/Don Shearman)

Cockatoo Island staff, Sydney, December 1914 (Flickr Commons/Don Shearman)On Wednesday, 5 August, the Argus carried a photograph of crowds milling outside the paper’s office to hear the latest news. Its editorial commenced: ‘There can now be little doubt that the British people are involved in what threatens to he the greatest war of all time’. The paper reported Sir Edward Grey’s statement to the House of Commons that Britain would assist France if Germany undertook hostile operations in the North Sea and what Britain would do if Germany invaded Belgium.

Before either of these events came to pass, the Australian Governor-General, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, made a proclamation under the Defence Act about ‘the existence of a danger of war’ and calling out the citizen forces for active service. Newspapers became subject to censorship.

Britain, if her own interests had been the sole consideration [said the Argus], might long since have precipitated the war. She has at last been forced into it by the claims of honour, and her people throughout the world will hail her decision with proud satisfaction and await the issue with courage and confidence.

While we have not attempted a comprehensive survey of public opinion, or even press opinion, it seems that initial cautiously positive attitudes to the outbreak of war were widespread and clear and replicated at all levels. The Argus echoed Grey, who spoke of ‘British interests, British honour, and British obligations’. Cook and Fisher and their colleagues expressed bipartisanship about the war, in the midst of an election campaign which had followed a particularly bitter period in national politics. (Douglas Newton points out, though, that Fisher was under some pressure to prove Labor was as willing to fight as the Liberals were. (2))

Further afield, the Argus reported great keenness in Deniliquin, Nagambie and Nhill for Australia to be involved and that ‘it only needs an appeal from the Prime Minister for volunteers and money to set these inland towns on fire with patriotic enthusiasm’. In Ballarat, some young men who had evaded drill under the compulsory youth service scheme came forward to offer their services in the crisis. Meanwhile, Australasia had beaten Germany in the Davis Cup.

___________________________________

(1) Douglas Newton, ‘At the birth of Anzac: Labor, Andrew Fisher and Australia’s offer of an expeditionary force to Britain in 1914’, Frank Bongiorno, Raelene Frances & Bruce Scates, ed., Labour and the Great War: The Australian Working Class and the Making of Anzac, Labour History (Special edition), 106, May 2014, p. 20.

(2) Ibid., p. 40.

See also a short piece on the Australian War Memorial site.

Note: The title of this highlights reel comes from President Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. Lincoln spoke in the closing weeks of the American Civil War, touching briefly on how the conflict began, describing how it developed, and looking forward to a future that he hoped would be better.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.