‘Great War navy’, Honest History, 27 March 2015

Alan Stephens* reviews In All Respects Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One, by David Stevens

Late last year Australia embarked on an extraordinarily extensive and costly five-year commemoration of ‘100 Years of Anzac’. The project’s official website, subtitled ‘The Spirit Lives, 2014-2018’, contends that it was the Anzac experience, and in particular the now legendary invasion of Turkey at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, that has come to shape our national self-image and which, in the 100 years since then, has largely defined what it means to be Australian. Above all else, the asserted innate characteristics of the Australian soldier – the ‘Digger’ – such as laconic bravery, cheerful larrikinism, irreverence towards authority, and mateship, are said to best represent our national character.

Seamen signal with flags, HMAS Australia, c. 1914-18 (Australian War Memorial EN0528)

Seamen signal with flags, HMAS Australia, c. 1914-18 (Australian War Memorial EN0528)

It might seem ironic, therefore, that, as David Stevens’ admirable new book reveals, in the period between Federation on 1 January 1901 and the Gallipoli landings 14 years later, it was through sailors and navies, not soldiers and armies, that Australia most vigorously expressed its evolving identity, its ties to Empire, and its understanding of the contribution of military power to national security. Moreover, the myth of the Digger notwithstanding, it was the operations of the Royal Australian Navy that made the most important contribution to the defence of Australia during World War I.

Isolated geographically and culturally, nervous about their neighbourhood, and unsure of their place in the world, in 1914 most Australians regarded themselves as true members of the British Empire, an attitude which in part explains why Australian foreign and defence policies were to all intents and purposes decided in London. The authority and wealth of the Empire was underwritten by the (British) Royal Navy, which for over a century had ruled the waves. It was thus both emotionally understandable and strategically logical for the national security policies of newly federated Australia to focus on sea power. If we were threatened, it seemed that only the RN could come to our rescue. It was the RN alone that could secure the so-called ‘sea lines of communications’ to the distant mother country, lines on which we were utterly dependent for trade, travel, and the ties that bind.

Before Federation each of the states had ‘some form of floating defence’, as Stevens puts it in the sometimes quaint but pleasing (at least to this reviewer) naval turn of phrase that is one of his book’s features. Those fleets were amalgamated as the Commonwealth Naval Forces before officially becoming the Royal Australian Navy in 1911. Early naval activities attracted enormous popular enthusiasm. According to the prominent MP and later prime minister, Joseph Cook, it was naval power that would ‘realize the promise of Federation’. A public holiday was declared to allow thousands to witness the first formal appearance of the Australian fleet at Sydney Harbour on 4 October 1913, with most interest centred on the flagship, HMAS Australia. The most powerful warship in the southern hemisphere, the 22 000 ton battlecruiser’s name had been chosen by Cabinet deliberately to emphasise the Navy’s status as a ‘national institution of prime importance’.

As the probability of war in Europe increased, there was considerable debate regarding the employment of the RAN, with differences centring on the distinction between local defence – that is, the immediate protection of Australia from raids, attacks on shipping, even invasion – and operations on the other side of the world. Notwithstanding that debate, it was accepted that once any fighting began, regardless of where the RAN was deployed, it would be placed under the control of the (British) Admiralty.

It was against that background that in August 1914 the Australian Navy went to war. The story of the RAN in World War I has of course been told before, most notably by the official historian, Arthur Jose, whose volume was published in 1928. No previous writer has, however, had access to the range, quantity, and quality of sources drawn on by David Stevens and most other works have not, frankly, been great reads.

One of the many merits of Stevens’ history is that it is a great read. Before becoming Australia’s leading naval historian, Stevens spent 20 years as a naval warfare officer; and it shows. He writes about all things naval – people, ships, navigation, weapons, tactics, service politics, leadership, training, traditions, the arcane vagaries of oceans, and much, much more – with an easy authority that is both informative and reassuring. His expression is clear and his book well- structured. And the story he has to tell is exceptional.

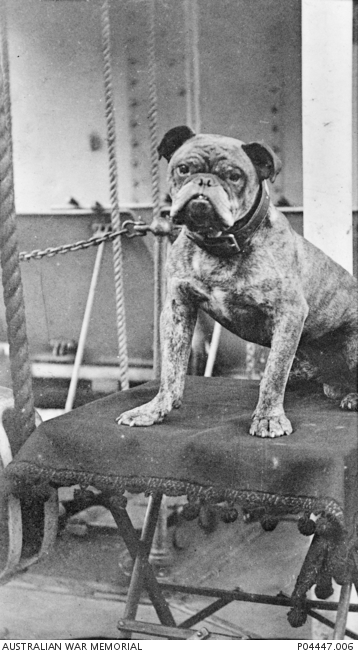

Punch Anzac, mascot, HMAS Australia, c. 1915-20 (Australian War Memorial P04447.006)

Punch Anzac, mascot, HMAS Australia, c. 1915-20 (Australian War Memorial P04447.006)

Contrary to the assertion ‘strangely’ made by Jose in the official history that on the outbreak of war the RAN was ill-prepared, Stevens demonstrates that it was a proficient fighting force. Officers and ratings were well-trained and experienced, and the fleet, while small, represented a good balance of capabilities, including, in addition to the formidable Australia, light cruisers, torpedo-boat destroyers, and submarines.

Nine months before Gallipoli the RAN was the first service from the British Empire to fire a shot in anger (at a German steamship trying to escape from Port Phillip Bay on 5 August 1914); it was the first Australian service to suffer a casualty (Able Seaman Bill Williams, killed near Rabaul on 11 September 1914); and, five months before Gallipoli, it provided Australia’s ‘first fighting hero’ (Commodore John Glossop, who commanded HMAS Sydney’s ruthless destruction of the German raider Emden near the Cocos Islands on 9 November 1914).

Most importantly, though, in the early months of the war, it was the RAN that made Australia safe. Two tasks in the Pacific and Indian Oceans were critical: neutralising German military bases and colonial territories and protecting trade and troop ship routes. Both missions were undertaken with impressive speed and efficiency as the Navy moved rapidly against Australia’s enemies in places as far apart as German New Guinea, Samoa and the Cocos Islands.

Thus, when the first convoy of soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force and their New Zealand allies sailed from Albany on 1 November 1914, there was a reasonable degree of assurance that they would reach their destination on the other side of the world safely (noting that Sydney broke away from that convoy to attack Emden). That was only the beginning of what was to become an unremitting, four-year-long campaign around Australia and throughout the Pacific and Indian Oceans of escorting, patrolling, blockading, mine-clearing, and the like. Often routine and unheralded, those activities constituted the foundation of Australia’s territorial security during World War I.

Simultaneously, from early 1915 onwards, the RAN began deploying units to the far reaches of the globe, sometimes as part of a larger RN force, sometimes independently. Separate chapters address these operations in East Africa, the Mediterranean, the North Sea, the North Atlantic, the West Indies, and China. That might seem enough in itself, but Stevens also properly finds room for the stories of naval aviation and of sailors fighting on land with the AIF or as engineering specialists.

From the many actions Stevens recounts, none is more remarkable than the penetration of the Dardanelles by the Australian submarine AE2 at 2:30 am on 25 April 1915, several hours before the first Anzac landing. At one stage AE2 had to remain submerged for 17 hours as its crew fought to survive in the most dangerous and hostile circumstances. So depleted was the oxygen supply inside the submarine that a match, once struck, would not burn. It was characteristic of the entire Anzac experience that AE2’s mission was extraordinarily heroic and ultimately a failure.

Although the book’s chapters are titled according to theatres of operations and campaigns, Stevens’ focus remains squarely on the men (and occasionally women – not many were involved) who did the fighting. Each chapter concludes with a pen portrait of a notable personality, ranging from admirals to able seamen. Perhaps because about half of the RAN’s leadership continued to be drawn from the RN throughout the war, there is an element of eccentricity in the RAN that is less evident in other Australian services. Claude Lionel Cumberlege, for example, liked to stride the deck of the ships he commanded with a pet black cockatoo on his shoulder, and was said to be proficient in three languages, ‘English, Australian and Profane’. The ascetic William Christopher Pakenham, regarded as ‘one of the finest sailors in the service’, always slept fully dressed, ‘collared and booted’, ready for action, and used only blue blankets on his bunk so that any fluff would not show on his uniform.

Sailors’ snow fight, HMAS Australia, North Sea, c. 1915-18 (Australian War Memorial P00385.002)

Sailors’ snow fight, HMAS Australia, North Sea, c. 1915-18 (Australian War Memorial P00385.002)

If some of the people were eccentric, so too were some of the Navy’s practices and experiences. Thus, prize money might still be paid for participating in the capture of an enemy ship, which could see a lowly RAN telegraphist win $300 000 in today’s money. And just before HMAS Pioneer left East Africa in August 1916 after an eventful deployment, her crew attended a ceremony staged by the Sultan of Zanzibar that included the sultan’s brass band, black vestal virgins strewing flowers, 200 coolies towing a captured German gun, 230 marching sailors and soldiers, five captured camels, a white donkey, and a baby hippopotamus.

It is disappointing but not surprising that the RAN’s pre-eminent role in making Australia relatively secure in the early months of the war has been forgotten. As Stevens points out, this has been primarily a matter of arithmetic. Between 1914 and 1918 the Permanent Naval Forces grew modestly, from about 3800 personnel to just 5050. By contrast, as witless generals reacted to the slaughter on the ground by demanding more cannon fodder, then more still, the AIF enlisted some 417 000 citizen soldiers. The almost unbearable loss of 60 000 of those young Australians in the tragedies of Gallipoli and the Western Front made it pretty much inevitable that the national memory of war overwhelmingly would become one of soldiers and armies.

Many Australians are concerned not only by the extraordinary amount of time and money being spent on commemorating the centenary of Anzac but also by its implications for how we think about ourselves. Those concerns should not extend to this excellent book, which makes a new and important contribution to our military history and which also, we might hope, will facilitate a more informed understanding of the realities of our national security.

* Alan Stephens is a Canberra-based historian and a former RAAF pilot, who has lectured and published extensively.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.