‘Does arms spending lead to war?’ Honest History, 4 November 2014

The concepts of Australian defence spending as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and as a proportion of total expenditure are both well-known. The former particularly has been argued pro and con. There is, however, another measure that deserves analysis and which is not nearly as high profile: Australian expenditure on arms imports (which covers everything from submarines and aeroplanes to small arms and flak jackets). This article looks particularly at this measure and advances some hypotheses for consideration.

Considering a paper prepared by the Parliamentary Library (David Watt and Alan Payne) it comes as no surprise that defence expenditure during the two world wars dwarfs that during other periods. (In 1944 it reached 40 per cent of GDP.) The main thing that leaps out, though, is that defence spending has been around two per cent of GDP since 1960. Indeed, (say Watt and Payne), it ‘has been in gentle decline since around 1988 … It is notable that the last time the defence budget was at 2 per cent of GDP was in June 1995.’

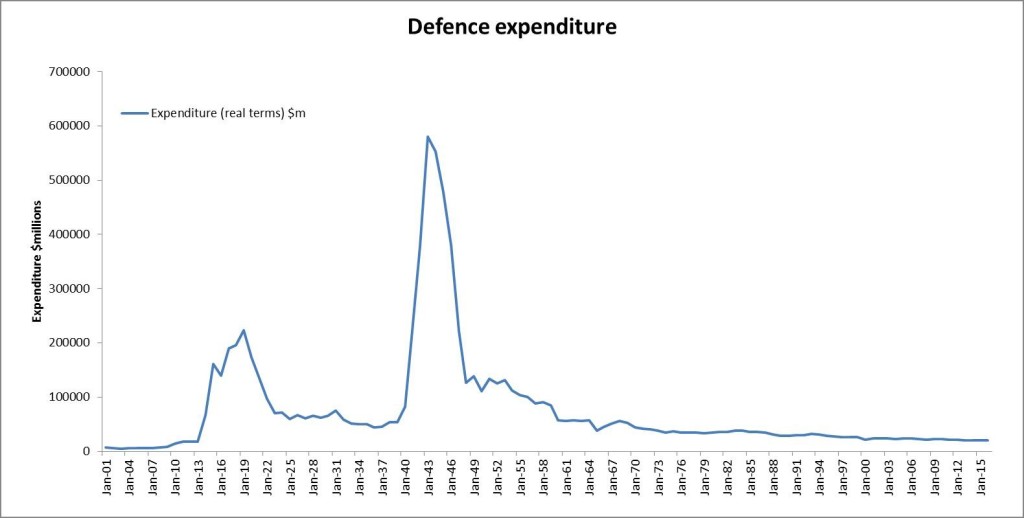

Graph 1: Defence spending in real terms

The dollars here are constant 2011-12 dollars. The relative flatlining from around 1960 (after World War II, Korea and the Malayan Emergency) is obvious – though there is an upturn during the Vietnam War around 1969. As noted above, for almost 20 years the line has represented less than two per cent of GDP. Yet, Australian military expenditure in 2013 was the 13th largest in the world. Clearly, it is misleading to look only at the two per cent measure.

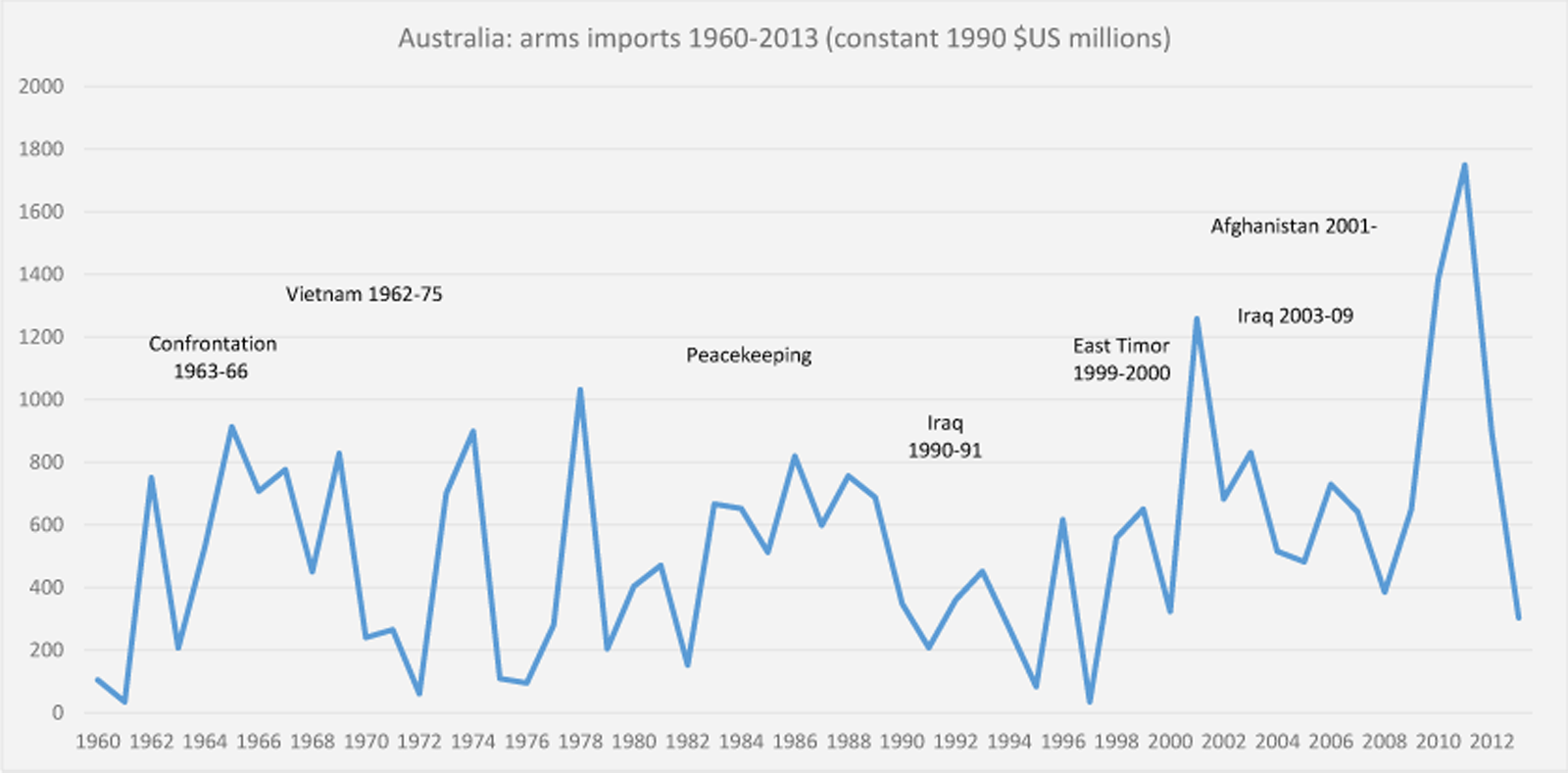

Graph 2: Expenditure on arms imports

The second graph comes from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) which has for many years collected defence-related statistics from around the world. We have retrieved this set of SIPRI statistics from the IndexMundi website (adding the final two years direct from SIPRI) but rescaled the graph a little to fit the page.

Note that these are calendar rather than financial years though that does not affect the long-term picture. The spend this time is in 1990 United States dollars in line with SIPRI practice; using Australian dollars or calculating the real dollars from a different year would not alter the essential picture. The text boxes refer to the official Australian involvements in war and peacekeeping, as listed by the Australian War Memorial. They are included to assist the statement of the hypotheses below concerning the relationship between conflicts and spending. The graph does not include the proposed expenditure on the Joint Strike Fighter, including $A10.8 billion on the actual planes, which was announced in Anzac week, 2014.

Expenditure on arms imports (Graph 2) is a component of overall defence expenditure (Graph 1). The relatively smooth line in Graph 1 is a function of the scale of the graph and the effects of other defence expenditure, such as on wages and salaries. Even allowing for these differences, the spikes and dips in Graph 2 are extreme. What accounts for them?

Four hypotheses regarding spending on arms imports in relation to wars

1. ‘War coming; spend up’

The first hypothesis is that spending on arms imports goes up when war is on the horizon. This hypothesis does not fare well, except perhaps with Confrontation in 1963-66, where a steadily-building perceived threat from Indonesia led to an Australian commitment to the F-111 aircraft. The F-111 project ran into difficulties and the first aircraft did not arrive in Australia until 1973, by which time Confrontation was a distant memory and the Vietnam War had waxed and waned. F-111 payments may explain the spike in spending in 1974.

This case emphasises that, even if foresight or prescience generates an initial commitment to spending, the actual outflows may be a long time coming. The long lead-times for military spending projects – even where they are not beset by problems, as many of them seem to be – probably condemn this hypothesis anyway: it will not be possible to wait until war is imminent to start buying defence materiel from overseas. (In a large-scale war, production would be heavily domestic anyway, as in World War II.)

This hypothesis seems to have a more general relevance, though, which is best summarised in the words of a former Chief of Air Force: ‘the world is a dangerous place’. Put another way, if ‘the price of liberty is eternal vigilance’ the price of eternal vigilance is eternal expenditure. Eternal vigilance justifies a continuing commitment to spending, whether or not there are imminent threats. The only question is at what level the spend should be and this is influenced by competing budgetary priorities.

2. ‘War in progress; spend up’

The second hypothesis is that spending on arms imports goes up once war is under way. This hypothesis applied during the two world wars (though note the point above about domestic production), to some extent during the Vietnam War and, spectacularly, during the Second Iraq War and the Afghanistan commitment.

Remember that Graph 2 is in real terms: the Second Iraq-Afghanistan spike dwarfs the Vietnam peak, even though the Vietnam War involved a far larger commitment of men and was more costly in terms of deaths and injuries than either Second Iraq or Afghanistan. Spending certainly goes up once war is under way but the lesson of Second Iraq and Afghanistan is that there is no relationship between the size of the war and the size of the spend on arms imports. Containing a war will not mean containing the spend if weapons are more expensive; small wars are compatible with the use of sophisticated weapons (such as drones) and may indeed demand them to make up for reduced manpower.

3. ‘Spend up regardless’

The third hypothesis is that there is only a loose correlation between war and spending on arms imports. Two points raised earlier tend to support this hypothesis. First, long lead-times mean that the threat may have long passed by the time the materiel is delivered. Secondly, there is the lack of fit between the size of the war and the size of the spend. There is in Graph 2 no consistent pattern of links between wars or threats of wars and spending on arms imports: the drawn-out, relatively low intensity, limited commitment Second Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts have a more obvious correlation with spending spikes than does the more spectacular Vietnam War.

Is the ‘eternal expenditure’ concept the best explanation then? Within it, can the spending spikes be explained by the increasing costs of more sophisticated ‘kit’ (to use a common military term for defence materiel), by the ‘lumpiness’ of outlays on expensive projects and by successful tradings-off against competing priorities in the Budget?

There is another possible explanation, though, one which requires splicing together a couple of potential drivers: the desire of military users for new and better kit meets the desire of arms producers to sell product. The sophisticated pitch of the seller finds an eager market of buyers seeking to update weapons, to be at the ‘bleeding edge’ of military technology. (The last-mentioned factor can be rephrased – as it has been by a former Chief of Army – as the need for service people to have the best possible protection in the front line, though that argument works better for personal protective gear and personal weapons than it does for, say, fighter aircraft and missiles.)

This interaction of buyer and seller deserves a closer look. The Australian market is very important to arms manufacturers, particularly American ones. Australia gets 76 per cent by volume of its arms imports from the United States. Over the period 2009-13 Australia was ranked seventh in the world in terms of imports of major weapons (accounting for four per cent of total deliveries, up from two per cent in 2004-08). Crucially, Australia in 2013 took 10 per cent of United States exports of major weapons, just ahead of South Korea as the United States arms industry’s biggest customer for these weapons.

What is the point of these statistics? Simply that, given the importance to the American arms industry of Australian customers, one can speculate as to the attractiveness of the deals and inducements offered to ensure that Australians keep buying. This is not intended to imply corruption: Transparency International ranks Australia as the ninth-least corrupt country in the world, out of 177 surveyed. On the other hand, the arms industry has been ranked by TI and SIPRI as one of the most corrupt there is, which has brought great cost to governments and citizens while benefiting buyers and sellers. Many former senior defence officers take up jobs or Board positions with arms suppliers.

While we are using this SIPRI resource, dated just a month before Australia announced its decision on the Joint Strike Fighter, it is worth quoting the SIPRI remarks on the state of play regarding that project; they reflect some Australian misgivings and reinforce the remarks above about the difficulties associated with defence materiel purchases.

The F-35 programme is the most expensive weapon programme ever. However, it is facing delays. Of 590 aircraft planned for export, only 5 have been delivered to date [March 2014] and several states have reduced the number that they plan to purchase or are considering less advanced alternatives.

4. ‘Return on investment’

The fourth hypothesis is that investment in arms creates an incentive to use them in war. Unlike the first three hypotheses, this one is not about whether war or the prospect of war leads to arms spending but, the reverse, whether arms spending leads to war. Ultimately, defence ‘kit’ is purchased for use; having arms ‘in readiness’ is the default position but using them in combat is always in prospect. What might influence the move from one condition to the other?

We start here from the assumption that arms – particularly major projects like joint strike fighters, drones and submarines – are expensive both in money terms (whether for purchase or development) and in terms of the political and career capital invested in them. We then put eight questions for consideration:

- Will ‘sunk costs’ provide an impetus towards the use of arms in combat? (In other words, will there be a disinclination to ‘waste’ all this investment?)

- Will the desire for a return on investment in arms influence military advice to governments which are considering involvement in war?

- Will the concern to achieve a return on investment also influence the response of governments to military advice?

- Will further pressure toward war come from the military desire to work successfully in combat environments with sophisticated ‘kit’, leading to promotion prospects for some and experience and training for all? (See Attachment A below.)

- Will there be a desire in government to support such opportunities for the military? (See Attachment B below.)

- Will arms sellers encourage moves to war to provide opportunities for ‘demonstrations in use’ of their products, leading in turn to future sales?

- Will the ‘return on investment’ and the ‘eternal expenditure’ spurs continually reinforce each other?

- Given the weight of all these drivers, to what extent will the desire not to place personnel ‘in harm’s way’ work as a countervailing factor?

Like the first three hypotheses, this hypothesis and its subsidiary questions are put for consideration and testing by readers. The ‘Comment’ function below is provided for that purpose.

Of course, most of these questions could apply to defence expenditure in general, rather than just to the arms component of it. That is a matter for another day.

Group portrait of five decorated Australian Flying Corps officers standing in front of an Avro 504K aircraft, Point Cook, Vic., c. 1919-20 (Flickr Commons/Australian War Memorial DAAV00160)

Group portrait of five decorated Australian Flying Corps officers standing in front of an Avro 504K aircraft, Point Cook, Vic., c. 1919-20 (Flickr Commons/Australian War Memorial DAAV00160)

Attachment A: Mark Corcoran, ‘The kill chain: Australia’s drone war‘, ABC News, 27 June 2012 (extract of article with emphasis added)

The Royal Pines Golf Resort on the Gold Coast is a long way from Afghanistan.

But it was there recently, at the Heli and UV Pacific aviation convention, that Australia’s top military drone commanders launched an extraordinary public relations offensive.

In one sense they were preaching to the converted; this gathering of aviation industry insiders was fascinated by the technology but displayed no interest in discussing the political or ethical considerations of this rapidly expanding form of warfare.

Beyond the gleaming display helicopters parked on manicured lawns, and inside a packed auditorium, Wing Commander Jonathan McMullan took to the stage.

He’d returned just days earlier from deployment to Kandahar in Afghanistan and was exuberant about the drone force he commanded, the Royal Australian Air Force’s 5 Flight. This technology, he proclaimed, was saving Australian lives and was now enthusiastically embraced by the troops on the ground.

“The capability? It’s like crack cocaine, a drug, for our guys involved – just can’t get enough of it,” Wing Commander McMullan said.

Attachment B: David Wroe, ‘Australia’s defence forces to be maintained at battle-ready status’, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 September 2013 (extracts of article with emphasis added)

Australia’s new Defence Minister, David Johnston, says he wants to keep the military battle-ready for further possible conflicts in the unstable Middle East and south Asia.

Senator Johnston said that after 14 years of involvement in overseas conflicts from East Timor to Afghanistan, the Australian Defence Force had a strong fighting momentum that should not be lost as troops return from Afghanistan.

In an interview with Fairfax Media, he said he plans to maintain and ”augment our readiness” for future fights, which will most likely be in the unstable region stretching from Pakistan to the Levant, including even fresh trouble in Afghanistan.

”It will be Pakistan across to Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Afghanistan. That’s the area where there will be instability and that’s the area that we might need to go back into at some point in the future.

”I can’t foresee that right now, but … if you were to look at where the next area of instability is likely to be – and we’re seeing it unfolding in Syria today – a contribution from Australia is most likely to be in that part of the world in the future. I think Pakistan is also highly problematic.” …

He said he was not preparing for any particular conflict ”in an alarmist sense” but was determined to build on the knowledge and skills the Australian Defence Force had gained running counterinsurgency operations in Afghanistan. That included exposure to enemy tactics such as the use of improvised explosive devices and fighting in urban areas among a civilian population ”against a very, very resourceful and callous enemy”.

“These are experiences that we’ve lived and breathed for 10 years and we’ve become quite expert in those things. And we’ve got to make sure those lessons are passed on to our soldiers in the future.

”Operationally, we’re starting to come down [in Afghanistan], so we’ve got to maintain some interest for the troops. They’ve got to keep training, got to keep a level of readiness.”

David Stephen’s article raises extremely important questions which should be at the forefront of Australia’s current defence review (but are not). While “security” is often equated with having the biggest, newest, most expensive weapons systems, we should consider the possibility that major weapons sales lower the threshold for going to war and contribute to regional and global insecurities.

Given the disastrous humaitarian, envionmental, economic and other impacts of modern warfare, as well as its propensity to make bad political situations far worse (as for example in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the intervention in Libya and others), its avoidance should be a top priority. Anything that emboldens leaders to take their country to war, such as a perception of superior strength, should be scrutinised and challenged.

Big ticket weapons are advertised as being in the cause of national security, jobs, and the advancement of science and humanity. Aggressive and deceptive marketing is not unique to the weapons industry of course, but the weapons industry’s products can come with price tags in the billions of dollars. To suppose that such outlays do not bring also some desire within the defence and government bureaucracies for them to be used at some stage, seems rather fanciful. Large weapons expenditures would seem, on the contrary, to provide a false sense of security and invincibility.

And , far from promoting stability and security, weapons advertising is targetted to areas of instability. In 2008 for example, the Asia Pacific Defence and Secuirty Exhibition (whose Adelaide opening was cancelled because it had been planned for, believe it or not, November 11) announced on its website that “Selected trends favouring increased defence spending are…….North Korean regime instabiltiy, disputed territorial claims, possibility of regional arms races……” and other trends all favourable to increasing weapons sales. This does not directly answer the question “What comes first – more weapons sales or greater instability?” , but it does illustrate the parasitic nature of an industry that wants to see war rather than negotiation as the preferred means for conflict resolution.

In the US,an investigation by the Public Accoutability Initiative (https://public-accountability.org/2013/10/conflicts-of-interest-in-the-syria-debate/) found that in the 2013 debate about whether to attack Syria, many defence-industry spokespeople provided media commentary urging miliitary action; their industry links were not disclosed to viewers /readers. In contrast to such blatant conflicts of interest, there is much recent media comment to the effect that efforts to maintain Western military dominance, be it in the Middle East or in the Pacific against China, is likely to elicit a strong backlash and undermine our security. An industry that has to hide behind a cloak of secrecy lest its agenda be dsclosed does not have our security at heart. Further open discussion of the questions raised by Stephens is to be encouraged.

David Stephens’ paper raises again the question of whether the strategies and policies Australia undertakes in the name of national security are part of the problem of its insecurity rather than part of the solution to its security.

The four hypotheses are open and thus invite discussion and debate. The eight questions at the end are, likewise, essential in any debate on national defence sensibly defined.

From this writer’s perspective, this debate might begin with a step back so as to see the assumptions – essentially items of political-religious dogma – underlying the need for Australia be ranked in virtually the same global position as a defence spender as it is an economic actor – 13th. Thus, not only is the world seen as a dangerous place, it is to be held at bay by an alliance system which declares it seeks a balance of power with all possible antagonists, though this tends to mean, in operational terms, a preponderance of power. Enemies are to be deterred from even thinking seriously about aggressive action by the credible threat of the unacceptable damage which would follow any aggression.

It is here that the Australia – US alliance over-determines Australian Defence Policy. Since alliances require interoperability in technology and tactics, they require continuous upgrading to the level of the dominant alliance partner which is also the main provider of both. The technology it supplies is always changing, always expensive, and it enjoys a monopoly position. Alliances, moreover, are run according to the dictates of the dominant partner’s interests which, in turn, means that dependent partners are obliged to have capabilities beyond those which might suffice for purely national defence. Overall, and leaving aside human, social, and political costs, they are economically expensive.

This is not so much the end of the problem as the beginning of it. Notwithstanding the economic costs, alliances are poor instruments of national security policy. Indeed, perhaps the most salient point that could be made is that the rigorous analyses done to date mandate not that those against alliances justify their respective positions, but that those who advocate them justify theirs’. The best single source for underwriting such a project are the works of John Vasquez which remain among the most prominent and systematic attempt to clarify the benefits of alliances in achieving peace for their members.

Surveying the field of relevant accounts and using a quite massive data base, Vasquez’s conclusion is a demolition of the pro-alliance case:

It is now clear that alliances do not produce peace but lead to war. Alliance making is an indicator that there is a danger of war in the near future. … This means that the attempt to balance power is itself part of the very behaviour that leads to war. This conclusion supports the earlier claim that power politics is an image of the world that encourages behaviour that helps bring about war.

He then proceeds to an interesting theoretical question but, in the context of this essay, a salutary political question:

Since it is now known that alliances, no matter what their form, do not bring about peace … what causes actors to seek alliances[?] (emphasis added).

To this general case which is central to David Stephens’ eight closing questions should be added the Australian record since 1945 which confirms the claim that alliances have been efficient instruments for involving the country in war. Interestingly, although the popular view is that Australia has been at peace since 1945, the record is a counterblast to it. For at least 50 operational years in this period of 69 years, Australian-Defence Force personnel have served in no less than five significant conflicts (Malayan Emergency, Korean War, Vietnam, Confrontation with Indonesia, two wars against Iraq, Afghanistan, and now the war against ISIS/ISIL in the Gulf as a direct, or indirect consequence of alliance membership.

Here, too, the hypotheses relating to Australia’s arms spending returns with additional salience. If alliances are always against something – usually, another alliance – and if they always require the upgrading of capabilities, then the logic of the antagonistic relationship prescribes high levels of arms expenditure and, most probably, arms racing. Again, this is not the end of the question. Arms racing, according to the statistical analyses undertaken by Michael Wallace some 35 years ago, has a greater than 80 per cent probability of escalating to war. Although Wallace’s findings are not universally accepted the most recent surveys of the arguments for and against support both Wallace’s conclusion and the stated need in David Stephens’ essay for an urgent reconsideration on how, why, and to what level Australia is armed the way it is.