‘Empire sun has set but do spiffing war yarns persist?’ Honest History, 2 December 2014

Some talk of Alexander

And some of Hercules

Of Hector and Lysander

And such great names as these.

But of all the world’s brave heroes

There’s none that can compare

With a tow row row, row row row row

For the British Grenadiers.

(The British Grenadiers, c. 1702; You Tube)

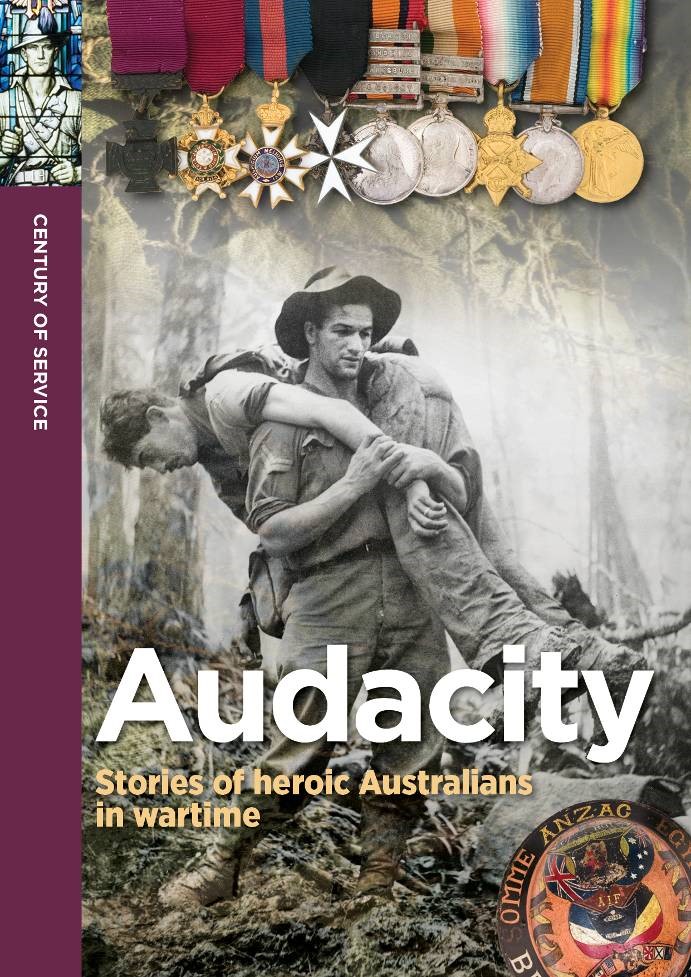

The literature of heroism has marched side by side with warlike ventures for centuries. It is instructive to compare two examples, published over 100 years apart: Deeds that Won the Empire: Historic Battle Scenes, by Dr WH Fitchett, first released in 1897, and Audacity: Stories of Heroic Australians in Wartime, by Carlie Walker for the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and the Australian War Memorial, published in 2014. These two publications bear some similarities but also notable differences. Together, they say a lot about how the State and its supporters promote causes, particularly to children.

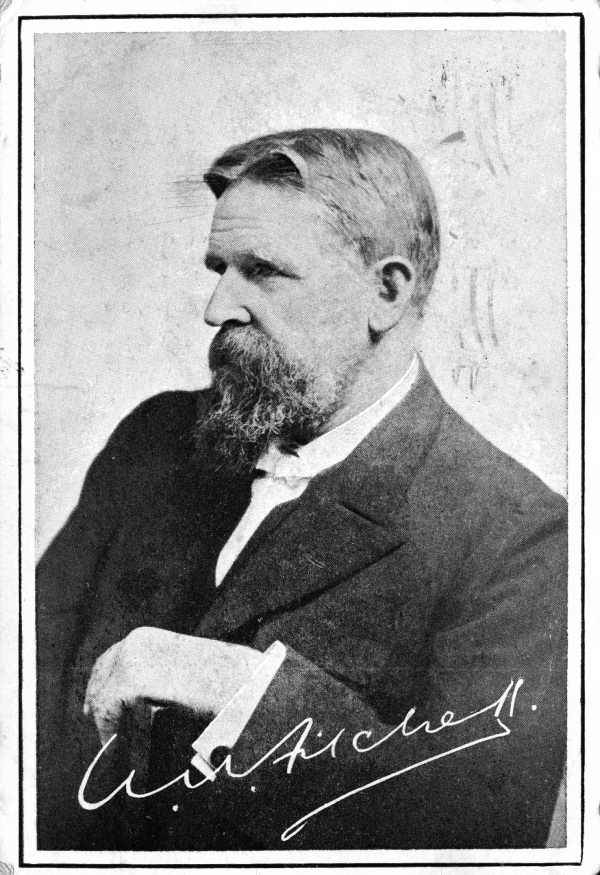

WH Fitchett (1841-1928) (Australian Dictionary of Biography/State Library of Victoria)

Deeds that Won the Empire (from here on called simply Deeds) appeared originally as articles in the Melbourne Argus. As articles and book, it became immensely popular throughout the Empire and was into its 29th printing by the time World War I began. The British Admiralty put the book in the library of every warship and General Monash read extracts from it to gee up the troops in France in 1918 (Holbrook, p. 76).

Deeds commences with a disclaimer that has a modern ring to it. ‘The tales here told are written, not to glorify war, but to nourish patriotism (Preface).’ We still claim not to glorify war but we go in for sentimental commemoration ceremonies that appeal to patriotism. Prime Minister Abbott said on Anzac Day this year, ‘the Centenary of Anzac should mean, for all of us, pondering anew the example of our mighty forbears … We commemorate Anzac Day every year and will commemorate the centenary of Anzac over the next four years because the worst of times can bring out the best in us.’ Commemorating war encourages us towards new efforts as Australians.

Fitchett went on, in words that might have been written by today’s Institute of Public Affairs or Minister Pyne or yesterday’s Prime Minister Howard.

The history of the Empire of which we are subjects – the story of the struggles and sufferings by which it has been built up – is the best legacy which the past has bequeathed to us. But it is a treasure strangely neglected. The State makes primary education its anxious care, yet it does not make its own history a vital part of that education. There is real danger that for the average youth the great names of British story may become meaningless sounds, that his imagination will take no colour from the rich and deep tints of history. (Preface)

How does heroism in war fit into this? Fitchett spells it out. War, he says, is ‘not all brutal’.

What examples are to be found in the tales here retold, not merely of heroic daring, but of even finer qualities – of heroic fortitude; of loyalty to duty stronger than the love of life; of the temper which dreads dishonour more than it fears death; of the patriotism which makes love of the Fatherland a passion. These are the elements of robust citizenship.

That list of qualities rings a bell. There is a comparable list in Audacity: devotion; independence; coolness; control; endurance; decision. Along with audacity itself these are some of the 15 qualities found in the Napier Waller windows surrounding the Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier at the Australian War Memorial. They are described as the defining qualities of Australian servicemen and women but they would be appropriate for any service personnel anywhere or indeed for any responsible citizen anywhere. They are, as Fitchett recognised, ‘the elements of robust citizenship’. We will come back to the relevance of these qualities.

Who are Fitchett’s heroes then? They are mostly found in the Napoleonic Wars, the conflicts in Europe and off its shores in the late 18th and early 19th century. So we have chapters on the Battles of Cape St Vincent, the Nile, the Baltic and other tussles against ‘Boney’, plus the Heights of Abraham from 1759 and a naval battle from the War of 1812. But the greatest of these are Waterloo (‘the story of the brave men who fought and died at their country’s bidding at Waterloo will become one of the great traditions of the English-speaking race’) and Trafalgar (‘It permanently changed the course of history’) and they get lengthy treatment.

Much of the book is conventional battle writing (with maps), but in a lively tone with lots of exclamation marks and superlatives (‘one of the most stirring incidents in the long record of brave deeds performed by British seamen’) and poems by people like Byron, Kipling, Macaulay and Sir Walter Scott. The word ‘florid’ springs to mind to describe the style but then it was 1897. There is much fighting against the odds and to a standstill, foolhardy ventures that come good, unlikely champions (teenage midshipmen, officers rising from their sickbeds, Irishmen), gifted amateurs and heroes dying at the moment of victory.

The death of Lord Nelson on the quarter deck aboard HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar (Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Trust/coloured engraving by J. Heath, 1811, after B. West)

The death of Lord Nelson on the quarter deck aboard HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar (Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Trust/coloured engraving by J. Heath, 1811, after B. West)

There is short shrift for caution: we hear of ‘the swiftness and vehemence’ of Nelson’s attack in the Battle of the Nile, ‘close and desperate fighting’ somewhere else, the ‘full and terrible note’ of the cheers and shouts of British soldiers as they charge. There are gallant commanders singled out (‘My plan consists in dying here to the last man’) and tragic heroes, often described as slim and boyish, like Wolfe in Canada and Freer and Lloyd in the Pyrenees in 1813. Some passages are almost homoerotic. Then, of course, there are the theatrical (and slightly built) Nelson and the Duke of Wellington, who seems to have become a crusty old buffer in his forties and kept it up for decades.

Opponents are generally brave and honourable (though sometimes failing in nerve). There is no lack of blood and guts (‘Die hard! my men, die hard!’ ‘One private reached the sword-blades, and actually thrust his head beneath them till his brains were beaten out’) but a bloody death is honourable, particularly if one lasts long enough to leave some inspiring final words.

The word ‘spiffing’ is archaic now but it might have been used at the time to describe the stories in Deeds. The Urban Dictionary has this to say about ‘spiffing’: ‘[v]ery posh and dated word meaning excellent, especially as used by upper-class toffs and rugger buggers’. One can imagine ‘spiffing’ echoing through the dormitories of the Upper Fourth at Melbourne Grammar; that is about the age at which Deeds was pitched, 15 years and up.

By contrast with Deeds, Audacity is quieter, almost reverent and directed at 10 to 12 year-olds. ‘Spiffing’ doesn’t work as an adjective here and the writing is not florid but plodding. But Audacity has other notable characteristics. First, it is friendly and familiar: all the heroes, nine male and two female (no females in Deeds) are referred to by their first names and their family connections are played up. It is Neville, Claire, Henry, Ernie and, of course, Sarbi, the Explosive Detection Dog. We hear about Ray Simpson VC’s Japanese wife, Shoko, Mark Donaldson VC’s childhood in Dorrigo and the young Harold Jarvie larking about in the Swan River. The message is that these are ordinary people who are thrust briefly into extraordinary circumstances where they do a good job and often get a medal for it.

The book has a solicitous warning at the beginning: ‘Most of these stories take place during wartime. You may feel sad after reading some of them.’ In fact, only the most sensitive of 12 year olds would be upset by the stories in the book. This is war writ bland, with the brave bits (and many of them are very brave) highlighted and most of the context scrubbed away. There is very little in Audacity of the stirring battle scenes and blood and guts that typified Deeds. The stories are much shorter than in Deeds and many of them have just as much about peaceful before and after war lives as about wartime exploits. War is ‘a challenge’ or ‘a job with a sense of purpose’. The book mostly avoids deaths in war. Only the death of Tom Derrick VC is dealt with in any depth – and that in a sentimental way – and other deaths of or at the hands of Australians are glossed over.

By contrast, the lessons to be learned are laid on with a trowel, spelled out in the chapter headings alongside the names of the people whose stories are told: outstanding and gallant service; bravery under fire; coolness and courage; for saving life, not taking it; daring conduct; refusal to admit defeat; leadership and courage; determination and skill; inspirational leadership; courage and calm; exceptional courage. The way to the objective is marked not by battles, as in Deeds, but by positive qualities; the book reeks of them. (While the objective of the deeds in Deeds is clearly ‘to win the Empire’, the objective of the protagonists in Audacity is personal: ‘each proved that they could be bold and courageous’.) An exercise asks readers to compare the deeds of VC winners Neville (Howse) and Mark (Donaldson), a century apart. to see if the definition of bravery has changed. Other tasks encourage students to consider what bravery involves, how protagonists feel in the thick of conflict or why they volunteered for such dangerous work.

Yet, the book reminds me in some ways of Look and Learn, a children’s magazine that used to arrive weekly in our house in the early 1960s. There are anodyne ‘Did you know?’ boxes about ejector seats, buglers, the meaning of the term ‘and Bar’ and the different pronunciations of the word ‘lieutenant’ across the services. (Not many people know that last one.) There are lots of paintings and photographs of military things, a map and a glossary of military terms.

Yet, the book reminds me in some ways of Look and Learn, a children’s magazine that used to arrive weekly in our house in the early 1960s. There are anodyne ‘Did you know?’ boxes about ejector seats, buglers, the meaning of the term ‘and Bar’ and the different pronunciations of the word ‘lieutenant’ across the services. (Not many people know that last one.) There are lots of paintings and photographs of military things, a map and a glossary of military terms.

Audacity is also very Australia-centric. The ‘Fast Facts’ boxes focus on war from the Australian perspective. Typical is the box on the ‘Air war over Europe 1939-45’ which gives a figure for Australian deaths in Bomber Command but says nothing about non-Australian or civilian deaths. On the same page, there is a photo of a night raid over Hamburg which makes a point about the photographing of targets but says nothing about 80 000 civilian casualties (42 000 deaths). Beneath the photograph is this exercise:

Peter [Isaacson] and his mates had competitions to see who could get closest to the action to get the best photograph. What challenges would crew members have faced doing this, and what does it say about their attitude to war?

To ask students to focus on games played by bomber pilots 70 years ago while ignoring the effects of their bombing is crass in the extreme.

Audacity stresses the deeds of individuals but leaves out the mass. War here is a chance for the individual to make a mark, to stand out from the crowd, to do something worthy of a medal. ‘You will … see lots of medals in the book’, readers are told. You bet you will, 17 colour pictures of them in 50 pages; that bravery wins prizes is a clear theme. Under a particularly colourful set of medals there is even an exercise: ‘Design your own medal to award to students in your school. What might it be awarded for? What colours and shapes would you use? Why?’ It is not spelled out whether the exploits deserving of such imitation medals should be warlike but the exercise carries the message that there are rewards awaiting exceptional performance.

This might be a good message but it does not need the military context. We noted above that the qualities portrayed at the Australian War Memorial in the Napier Waller windows are universal human qualities, not exclusively those that soldiers might display. Surely ‘robust citizenship’ can be demonstrated mostly free of a khaki tinge? Could there be a book about audacity which illustrated this worthy quality with no more than proportionate reference to military people, war stories and medals?

Of course there could. Such a book could include stories about policewomen and men, firefighters, search and rescue personnel, disabled people who achieve great things against great odds, crusading journalists, whistleblowers, conscientious objectors, child abuse or rape victims who give evidence, and soldiers, particularly soldiers who struggle courageously against the after-effects of war service. But then a book with these stories in it would not be funded by the Australian War Memorial or the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. War and heroism, ‘sacrifice’ and patriotism remain their preferred focus.

World Health Organization workers gearing up to go into old Ebola isolation ward in Lagos, Nigeria, August 2014. A hot zone is an area where patients are being treated and where occupants are at highest risk of being infected (Wikimedia Commons/CDC Global Health/Bryan Christensen)

World Health Organization workers gearing up to go into old Ebola isolation ward in Lagos, Nigeria, August 2014. A hot zone is an area where patients are being treated and where occupants are at highest risk of being infected (Wikimedia Commons/CDC Global Health/Bryan Christensen)

Audacity, according to the World Socialist Web Site, ‘presents an entirely idealised and sanitised version of war with medal recipients glorified as heroes who “sacrifice” for “freedom” while demonstrating bravery and loyalty towards “their job, their mates and their country”’. Deeds and Audacity are both dishonest in their different ways. The qualities extolled are the same but the methods differ. Audacity sanitises where Deeds glamourises. Audacity pulls punches on war to focus on individual acts of daring; Deeds lauds the warrior’s death.

Both Deeds and Audacity are propaganda. They gild the lily, they suppress evidence, they tell only part of the story in the interest of recruiting children to a patriotic cause. If either book finds its way into the hands of today’s children – and Audacity certainly will – it will need to be treated with great care and countered with plenty of other materials which put a more honest and balanced view of the nature of war. Or binned.

Appendix: A literary comparison

‘This [the Peninsular War] was, perhaps, the least selfish war of which history tells. It was not a war of aggrandisement or of conquest: it was waged to deliver not merely Spain, but the whole of Europe, from that military despotism with which the genius and ambition of Napoleon threatened to overwhelm the civilised world.’ (Deeds, ‘The night attack on Badajos’)

‘Australians don’t fight wars of conquest. We fight wars of freedom. We fight for peoples’ right to live their own lives and to worship in their own way and for their duty to respect others’ right to do likewise.’ (Prime Minister Abbott, Address at Recognition Ceremony, Tarin Kot, Afghanistan, 2 October 2013)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.