‘Divided sunburnt country: Australia 1916-18 (28): More on the 1917 Great Strike in Australia’, Honest History, 27 August 2017

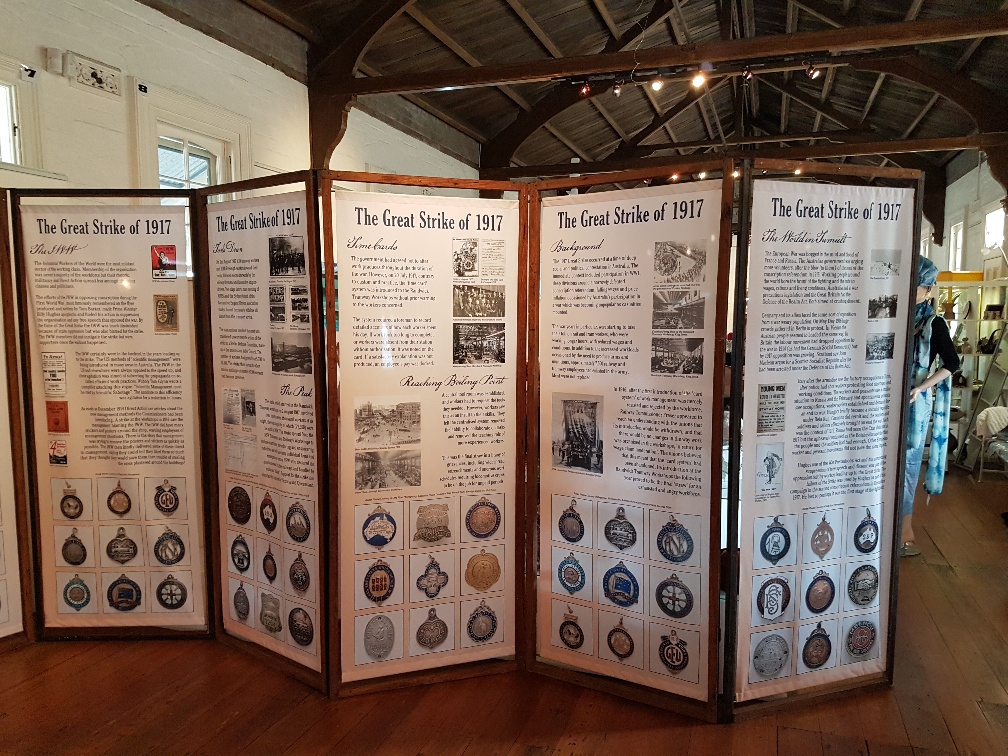

Update 28 August 2017: Unions NSW advises of its exhibition on the Great Strike. See comment below – and three pictures of the exhibition (courtesy of Unions NSW). Also, there is a podcast developed as part of the Carriageworks project referred to below – it incorporates oral history testimony collected in 1987 and 1988 as part of the Bicentennial Oral History project.

The ‘Divided sunburnt country’ series

Adjacent to the meandering wheel-tracks of the Anzac centenary/centenary of (Australian Defence Force) service official bandwagon, some hard-working historians today continue to offer insights into other, non-khaki, things that were happening a century ago. One such was the large strike which affected the railways and tramways, particularly in New South Wales but also in other states, in August-September 1917. We looked earlier this month at the beginnings of the strike and here are some more sources.

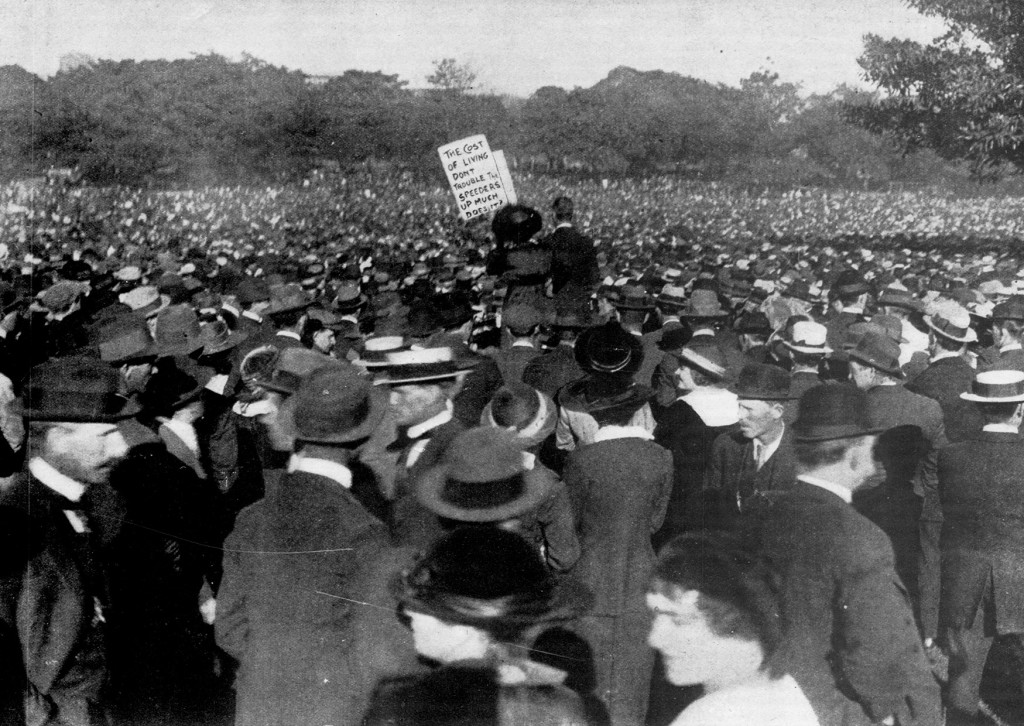

Demonstration outside NSW Parliament during the strike (Carriageworks)

Demonstration outside NSW Parliament during the strike (Carriageworks)

Phil Cashen’s Shire at War blog, often linked from Honest History, has a long article on the strike, both generally and for its impact on Gippsland, Victoria.

The Great Strike of 1917 was a conflict that went beyond industrial action [says Cashen], as large scale as this was. It is possible to see it more as a wider working-class revolt than a series of strikes. Certainly by 1917 there was considerable disaffection in the working class. There was “war weariness” but the War had also eroded real wages. Price rises had been extreme. There was also war profiteering. Above all, there was widespread concern that hard-won, pre-War industrial conditions were being eroded under the cover of patriotism.

Cashen looks also at the industrial politics of the strike, the accompanying mass demonstrations, the treatment of scabs, why the strike ultimately collapsed, and why unions were relatively weak in country areas, like the Shire of Alberton. Cashen also shows the anti-strike attitudes of the local rural newspapers and politicians.

It is also important to acknowledge that the rural communities also viewed the Great Strike as a direct threat to the War effort. As they saw it, the union movement was undermining the nation’s ability to prosecute the War. At the very least, the series of strikes was a major distraction and drag on the Hughes Government’s ability to proceed with its singular focus on maintaining Australia’s commitment to the Empire. At their worst, according to the official narrative, the strikes were intended to cripple the Hughes Government and pull Australia out of the War. The strikes were overlaid with accusations of treachery, if not treason.

Cashen’s concluding paragraph reiterates the depth of the divisions that the strike indicated and suggests that the unrest the strike provoked helped in the defeat of the second conscription referendum later in the year. ‘As the workers saw it, the impact of the War was now being carried disproportionately by the urban working class.’

The World Socialist Web Site also looks closely at the strike. Elle Chapman and Richard Phillips have a review of the Sydney Carriageworks/City of Sydney exhibition on the strike.

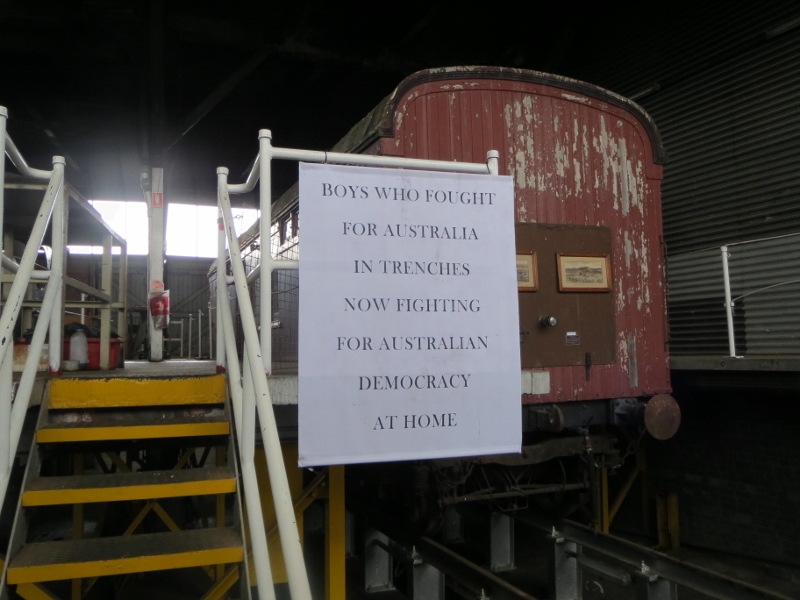

Australia’s federal and state governments reacted viciously against strikers, denouncing them as “traitors” and “enemies of civilisation”. Twenty trade unions were deregistered and workers sacked or blacklisted. Thousands of armed scabs were mobilised, one of whom shot and killed a protesting worker in Sydney a few days before rail union officials capitulated to management demands and ordered the strikers back to work …

The exhibition, which runs until August 27 at Carriageworks—the former Eveleigh Railway Workshops and a centre of the strike—punctures the official patriotic-militarist mythology about Australian involvement in World War I and makes clear that the home-front was dominated by intense class battles.

This post includes 15 minutes of documentary footage of the strike and some other illustrations. Recommended. Note also the telling final paragraph of this post, which sums up the differential treatment of parts of Australian history.

Over the past two years the Australian government has spent $35 million on a pro-war, interactive exhibition, The Spirit of Anzac Centenary Experience, that has been presented in 23 cities and towns across the country. By contrast, 1917: The Great Strike [finishing today] is only on in Sydney and will not be shown anywhere else in Australia.

Strikebreakers at Taronga wharf during the strike (NLA/Beer Studio/Mosman1914-1918)

Strikebreakers at Taronga wharf during the strike (NLA/Beer Studio/Mosman1914-1918)

The World Socialist Web Site also has a lengthy interview with Laila Ellmoos, curator of the Carriageworks exhibition. ‘Of course’, says Ellmoos, ‘many things have been done on the centenary of World War I, but the events covered in this exhibition are very different and they disrupt the memory of what people generally know about the war’.

Asked why issues of class conflict and inequality at home during the Great War are generally buried today, Ellmoos responded:

I think because people like an uncomplicated line. Of course, there is the engendering of patriotism and that sort of thing—and that was very intense during the war—but there is a tendency today to reject complexity. The world we live in—of social media, twitter and the promotion of bite-sized messages—doesn’t allow or enable complexity.

Ellmoos speaks about the attempts at the time to suppress the film excerpted at the exhibition, about the issues behind the strike itself, about the central role of worker rank-and-file, the death of the unionist Mervyn Flanagan, attempts to slander strikers, and so on.

For general background, try Joan Beaumont’s Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War (2013), pp. 329-35, and Robert Bollard’s In the Shadow of Gallipoli: the Hidden History of Australia in World War I (2013), especially chapter 6.

Unions NSW has had it’s own exhibit at Sydney Trades Hall. It began on 20-th July – the anniversary of the introduction of the time card system. It is designed to be a touring show and easily transportable. It has been in Goulburn, at union conferences, will shortly be in Bathurst and will be at the National Labour History Conference in Brisbane. We aim to cover the international context and the circumstances that lead to such anger amongst workers and communities. Much of the Carriageworks exhibition was drawn from our original materials. Unions NSW houses a very large collection of trade union historical materials. The touring material is easily transportable, is printed on fabrics and has its own hanging system if people have a large room and are interested in viewing. It can be supplemented with some of the Carriageworks material now that that show is over. Photos available. Contact me ntowart@unionsnsw.org.au