The Divided Sunburnt Country series

‘Divided sunburnt country: Australia 1916-18 (16): Conscription miscellany – and mainstream avoidance’, Honest History, 4 November 2016 updated

Update 16 November 2016: review of Archer, et al, ed., The Conscription Conflict and the Great War.

‘No’ ascending

One hundred years ago this week, people were still counting votes in the conscription plebiscite and many of them were wondering what would happen next. The Age in Melbourne referred to a ‘political crisis’ but Prime Minister Hughes was giving nothing away:

Mr Hughes’s general demeanour is certainly not that of a man who has received a check. Never at any time in his political career has he appeared to have a more hopeful outlook. Those who expected to find a disconsolate, dejected looking Prime Minister will find instead a decidedly cheerful optimist. The future seems to have nothing disagreeable for him.

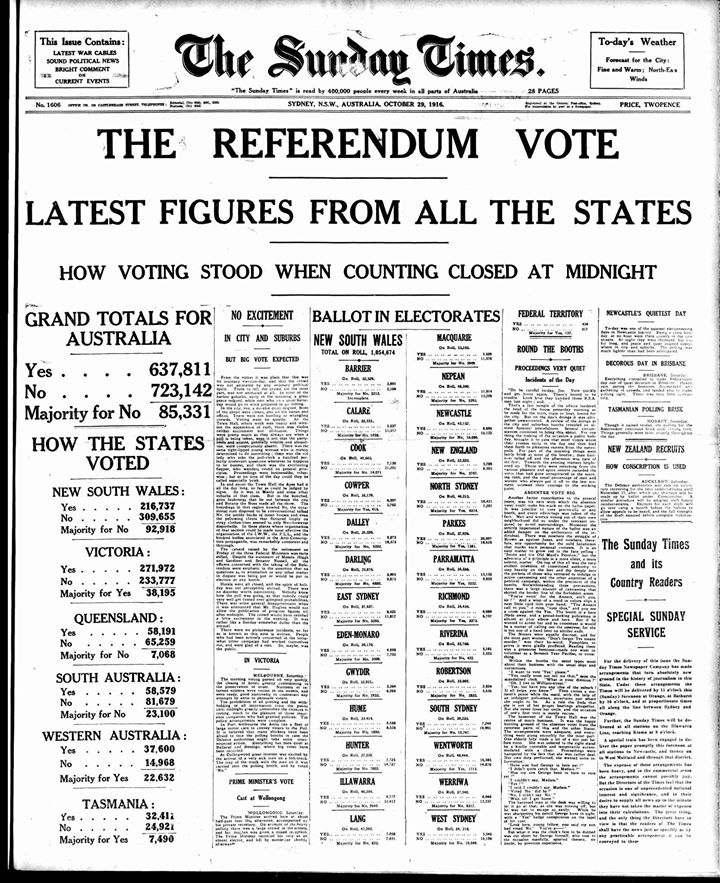

First results, Sunday, 29 October

First results, Sunday, 29 October

The progress count in the papers of 2 November showed the ‘No’ vote ahead by 81 000 votes but even by Saturday, 4 November, the result was still uncertain. The Australasian, looking back at voting day, recalled that ‘Everywhere the expression on the faces of the voters showed them to be in deadly earnest. Nor were ever two factions more sharply divided in opinion.’

Hughes’s newspaper supporters were represented by the Melbourne Argus, which was pleased that the ‘weaklings’ in Cabinet had left. (Hughes had been expelled from the ALP.)

Assuming that the referendum vote goes against conscription, Australia must still play as creditable a part as it can in the war, and the people are more firmly convinced than ever that only under Mr. Hughes’s control have we a chance of rising to our responsibilties.

On the anti-conscription side, the Australian Worker under the heading ‘Hughes must resign’ said this:

With a painful slowness the vote of the people against the curse of Billy Hughes is being disclosed. Every batch of negatives seems to be wrenched like a tooth from the dripping jaws of Militarism.

Vida Goldstein in the Woman Voter had this to say: ‘The Government – what there is left of it – is in a pitiable plight, but the people have their faces turned towards the light’.

100 years on

A century later, mostly off the radar of the mainstream media and the official commemoration industry, articles have been written, seminars have been held and an important book has been launched. Small circulation blogs have been active also. (The links go to complete articles and speeches and are well worth following up.)

Veteran political activist, Hall Greenland, wrote for New Matilda: ‘This week marks the centenary of arguably the most democratic event in Australia’s history. But it is one the establishment would rather forget.’ Greenland outlined the forces for and against conscription, their reasons, and the difficulties the ‘antis’ experienced in having their case heard. He touched on the class aspects of the struggle and the ‘terrorist’ scare surrounding the activities of the Industrial Workers of the World.

Historians of the left, right and centre agree [concluded Greenland] that the ‘No’ victory was mainly a victory for the Labor movement. The brilliant journalism of [Henry] Boote [of the Australian Worker], the activism of the Left and the fear of “coloured” workers replacing conscripts all played their part in mobilising the movement.

Greenland looked also at the role of farmers, Archbishop Mannix (minimal in the first vote) and women on the ‘No’ side.

What is incontestable is that in the midst of war Australians refused to give their rulers the power to compel men to kill or be killed. And the refusal was repeated 14 months later in a second referendum … It is a comment on our age that the only significant institution to celebrate this signal event is Australia Post – with a special stamp.

Glenn Davies in Independent Australia had another non-mainstream media overview.

Glenn Davies in Independent Australia had another non-mainstream media overview.

At the National Library, a seminar chaired by Honest History’s Peter Stanley heard from historians Joan Beaumont, John Connor and Michael McKernan. The Canberra Times reporter, Matthew Raggatt, caught the theme that the conscription plebiscite was a victory for grass-roots activism, despite most newspapers supporting the ‘Yes’ case.

Update 7 November 2016: Michael McKernan has kindly given us his notes from the National Library seminar; they are here. McKernan gives an interesting cameo of conscription and the war in Jugiong, NSW. It may be compared with the Gippsland material in the Shire at War blog (scroll down a bit below).

Then there was the seminar at the National Archives on 4 November, which included Frank Bongiorno talking about why Australians got so emotional about conscription. On the ‘No’ side this seemed to be because people felt their freedom was being threatened.

On 29 October at the ANU, Joan Beaumont launched the book The Conscription Conflict and the Great War. Professor Beaumont said:

The conscription debates [1916 and 1917] were … infused with passion and hysteria as mass grief and frustration at a war that seemed beyond the power of any politician or military commander to end was deflected onto opponents at home.

Professor Beaumont reminded us of an important point, often overlooked, that

the home front is in its own way as important as the battles fought on the Western Front and in Palestine. Certainly a remarkable number of Australian men enlisted and served overseas. But most Australians stayed at home. Many of these were women and children; but even among men of aged 19 to 60 years, nearly 70 per cent did not enlist.

Professor Beaumont’s speech is a good introduction to the new book, which is edited by Robin Archer, Joy Damousi, Murray Goot and Sean Scalmer and includes chapters by the editors, Douglas Newton, Frank Bongiorno, John Connor and Ross McKibbin. The book had earlier been launched in Melbourne by Bill Shorten and in Sydney by State opposition leader, Luke Foley. Bill Shorten said, among other things, ‘The moral judgments, the character attacks, the righteous indignation, the bitter condemnations and the thundering denunciations leap out from these pages’. He struck the right commemorative balance.

We live in an Australia united in its respect for the memory of those who served. But a century ago, this was the command post of a divided home front. A key battleground in a complex, white-hot national debate. Arguments as high-level and intellectual as the balance between liberty and loyalty … the limits of compulsion in a democracy, the moral purpose of solidarity.

He also drew some sly comparisons with current politics.

Similarly, in Sydney, Luke Foley spoke of ‘a tale of an Australian Prime Minister, unable to convince his own party room of the merits of a big reform – one close to his heart, one he considers essential for the nation – forced to bypass the normal processes of Parliamentary debate and legislation’ and let his listeners draw modern parallels. He presented the case of Broken Hill, many of whose men enlisted, but where 80 per cent of the votes in South Broken Hill were against conscription. Other working class and rural communities in New South Wales had similar results.

In their majority Australians, and most especially working class Australians, supported the war and opposed conscription. They wanted to win the war and they wanted to win it their way. They wanted to defeat Prussian militarism, but not by imitating it. They wanted to win by holding to the values that were central to Australians understanding of themselves and their newly minted nation – freedom for the working man and a fair go for all.

He went on to note the significance of death in war but the need also to put it in context.

This year is the centenary of Verdun and the Somme. It is right and proper that those battles are commemorated. But, for Australians, a complete understanding of the Great War will only be gained by reading and thinking about the conscription debates, their outcomes and their meaning.

Blogger Janine Rizzetti (The Resident Judge of Port Phillip) attended the Shorten launch and wrote about it.

Melbourne Trades Hall decorated for book launch (Janine Rizzetti).

Melbourne Trades Hall decorated for book launch (Janine Rizzetti).

In the setting of the oldest operating Trades Hall in the world, he [Shorten] noted that this was the geographic, political and emotional centre of the “no” vote in a debate that certainly did not exemplify the much-lauded “golden age of civility”. To the contrary, it was bitter, vindictive and spiteful and far worse than what passes for debate today.

Janine took a picture of the outside of the launch venue, the Melbourne Trades Hall, and we have borrowed the picture here. There is a famous picture of the same building in May 1916 during the big conference of May 1916 that began the organisation of to organise he anti-conscription campaign.

Among other blogs, Phil Cashen’s Shire at War, down South Gippsland way, has had lots on recruitment and conscription, including this analysis of the local ‘Yes’ vote and this on who were the main local supporters of the ‘Yes’ case. The ‘No’ campaign in Alberton Shire was insignificant but the ‘No’ vote seems to have been about one-third. There is more to come on this blog, which is well worth following. (More on ‘No’.)

Rounding off with a post that has been around for a while, the Living Peace Museum has an extensive collection of resources curated by another veteran anti-conscriptionist, Michael Hamel-Green. Michael wrangled the Brunswick-Coburg conscription events last week; Brunswick, of course, was where John Curtin was particularly active during the 1916 campaign. Update 8 November 2016: The Resident Judge of Port Phillip blog (Janine Rizzetti) has a rundown on Brunswick activities. Recommended.

We may feed more into this miscellany as material comes to hand. Our own review of The Conscription Conflict and the Great War has been posted (16 November 2016).

Clear of the mainstream

Meanwhile, the main daytime attraction at the Australian War Memorial on 28 October, the centenary of the first conscription plebiscite, was ‘Story Time’ for the kiddies at 10.30 am. (‘Hear stories of brave animals, extraordinary people, and faraway places, brought to life through puppets, uniforms, and educational toys’.)

Why is this momentous occasion, the Great War conscription struggle, being given so little play by the mainstream commemoration industry and its handmaidens in the media? Frank Bongiorno of the ANU perhaps put his finger on it, opening the Labour History Society’s 29 October seminar: there is a preference for uncomplicated history, history without too many moving parts.

The comfortable narrative of the Great War – or any Australian war – is blokes in khaki, mates together, doing heroic things. ‘It is not about war. It is about love and friendship’, pipes Director Nelson from the Australian War Memorial. War cooked that way is ideal for sentimental remembrance a century on. A country which was deeply divided, between volunteers and ‘shirkers’, between Catholics and Protestants, between unions and capital, between family member and family member, and where governments surveilled citizens under the guise of ‘War Precautions’, is much more difficult to squeeze into a Nelsonian or FitzSimonsian mould.* Nor does it fit a 90-second soundbite on an entertainment-oriented television news broadcast. Sentimental remembrance is the ticket; a complex, knotty, uncomfortable issue is not.

* Note though that Dr Nelson did say this in 2014 about Great War conscription: ‘[Australia] to its immense credit and our pride, twice rejected conscription’ (emphasis added).

Anti- flyer 1916, Australian Labor Party (AWM RC00336)

Anti- flyer 1916, Australian Labor Party (AWM RC00336)

Pro- flyer, 1916, Australian Nationalists (AWM RC00305)

Pro- flyer, 1916, Australian Nationalists (AWM RC00305)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.