John A. Moses

‘Conflict endemic to the human condition? A note’, Honest History, 8 April 2015

The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus (c. 535-475 BC) commented on war as follows: ‘We must know that war is common to all, and strife is justice, and that all things come into being through strife necessarily’. That is one translation. The more famous is that by Leopold Ranke (1795-1886) and the English rendition runs like this:

War is the father of all things. Out of the clash of opposing forces, in the crucial moments of danger – collapse, resurgence, liberation – the most decisive new developments are born. [1]

Hegel 1831 by Jakob Schlesinger (Wikipedia)

Hegel 1831 by Jakob Schlesinger (Wikipedia)

Ranke’s endorsement was in his famous tract, The Great Powers of 1833. It was by then paradigmatic in Prusso-German conservative thought. GWF Hegel (1770-1831), nicknamed (by von Srbik) the ‘Royal Prussian State Philosopher’ had already been teaching the same thing. [2] By the 1880s, after the three successful wars of German unification led by Prussia, scarcely anyone doubted that proposition. And when a Swiss professor of international law, Johann Kaspar Bluntchli, in 1888 published on the subject a work with pacifist aims, Field Marshall Helmut von Moltke (Retired) wrote to him politely but included the following criticism.

Eternal peace is a dream and not a beautiful one at that, and war is part of God’s ordering of this world. In it, the noblest human virtues develop: courage, self-abnegation, loyalty to duty and willingness to sacrifice one’s own life. Without war the world would sink into a quagmire of materialism.[3]

No doubt there were generals in the British army who thought very much the same thing. The difficulty with Prussia-Germany was, however, that these views pervaded the entire political culture; there were very few pacifists. In Britain there was among the middle and upper classes a ‘Whig tradition’, there were outspoken opponents of war, and there was a loyal Opposition in parliament. Moreover, the parliament controlled the military budget.

This was not the case in Bismarckian Germany. Indeed, with the ‘Prussianisation’ of Germany in 1871, a new kind of power state emerged on the scene. Prussia had virtually hijacked Germany. Although Germany had a parliament elected on adult male suffrage from a variety of parties, including anti-war parties, the so-called constitutional monarchy did not provide for cabinet government; rather the Chancellor was nominated by the Kaiser and he chose his ministers from outside the legislature. Bismarck provided that the army budget was only voted upon every seven years (changed to five years in 1893). This effectively emasculated the Reichstag’s right to vote supply and, bearing in mind that the army budget was the largest item in the federal budget, it was a device to sustain militarism by stealth (if militarism is defined as a system in which military objectives are prioritised over normal civilian concerns).

Bismarck 1871 (Wikimedia Commons/Bundesarchiv)

Bismarck 1871 (Wikimedia Commons/Bundesarchiv)

The domestic history of the Kaiserreich from Bismarck to Kaiser Wilhelm II was characterised, as many historians have ascertained, by a determination by the ruling classes to suppress democracy at all costs – and ruthlessly, if deemed necessary. Bear in mind that Germany had the largest and best organised labour movement in Europe, that is, the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and its allied trade unions. As its chief ideologist, Karl Kautsky (1854-1938), affirmed, it was indeed a revolutionary party but not a revolution-making party. In short, it was a vigorous Labour Party which, by the 1912 elections, was the largest party in the Reichstag and, in a real liberal constitution, could have been part at least of a coalition government. The ruling classes, however, were determined at all costs to block the rise of democracy.

As numerous historians such as Fritz Fischer, Wolfgang Mommsen, Dieter Groh and others have observed, the Kaiserreich was internally a very unstable political entity. Right from the beginning it was unable to normalise its foreign relations. Security after the defeat of France in 1870 could only be conceived of in terms of military alliances with other monarchist powers – Bismarck’s concept of being a trios to keep France isolated. Hence, the prioritisation of military solutions.

Domestically, the internal enemy was Social Democracy, as the anti-socialist law of 1878-90 illustrated; the law effectively turned the Reich into a police state. When the law lapsed, the young Kaiser sought in vain to mend fences with organised labour but only on his terms. With the SPD in the Reichstag becoming ever more vocal and the trade unions demanding a more liberalised social policy, it was clear that the ruling classes had great difficulty in finding a solution to both the foreign policy and the labour question. They suffered from a perennial Konzeptionslosigkeit, that is, a poverty of ideas for solving the great issues of politics. Instead, seemingly clever ways of diverting the concerns of the population from the structural inequities of the Reich were devised such as Kolonialpolitik (colonial policy) and Flottenpolitik (naval buildup (Eckart Kehr).

While Kolonialpolitik could have been a means of strengthening peaceful ties with Britain it was not pursued as such and instead the disastrous naval expansion program, engineered by the Kaiser through Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, was taken up at great cost with the illusory aim of ultimately outbuilding the Royal Navy and eventually destroying it as the major obstacle to fulfilling Pan-German dreams of world domination.

Hatred of Britain was about the most absurd basis imaginable for devising a rational foreign policy. And, while not a few generals deplored the expenditure on the ‘luxury fleet’, they made up for it by sharing Tirpitz’s hatred of the English, for whose military prowess they had the utmost contempt. At least the Schlieffen Plan, which had been designed to guarantee the defeat of France in a matter of weeks, made no provision for the possible intervention of a British Expeditionary Force.

So both the Tirpitz plan for the navy and the Schlieffen plan for the army were either flawed or based on a gamble, a vabanquespiel, a last throw of the dice with all one’s resources in the hope of a spectacular win. One wonders why such highly educated men would take such a risk. What, indeed, did the ruling elite hope to gain? The answer is:

- externally, as the September war aims program of 1914 makes plain, the twin grand objectives of Mitteleuropa and Mittelafrika;

- in Europe, the occupation of Eastern France, Belgium and a special arrangement with neutral Holland while, in the East after the crushing of Russia, the occupation of all the foreign principalities and provinces from the Baltic to the Black Sea, with Russia to be driven back behind the Urals – this was largely realised in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918;

- other plans such as the Berlin-Baghdad railway project, aimed at ultimately driving the British out of India, for which cloak-and-dagger plans for running German guns to assist Indian rebels to overthrow the Raj from within had long been in place – the same concept was applied to Ireland;

- in Africa, the Belgian Congo and the Portuguese colony of Angola would add to the existing German protectorates while the British possessions would either be ceded or occupied by German colonial troops.

What all this presumed, of course, was the destruction of the Royal Navy, an outcome for which Alfred von Tirpitz had long yearned. The British and Dominion governments were long aware of this aim; Australia, New Zealand and South Africa would be exposed, defenceless outposts, easily subjected to German political will. The dreams and delusions of German war aims knew no bounds.

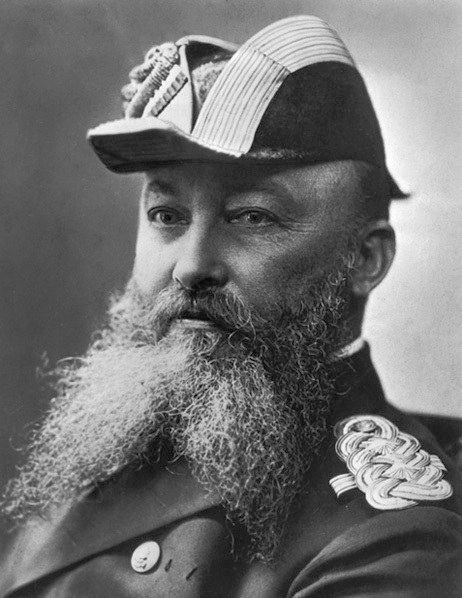

Alfred von Tirpitz (Wikimedia Commons)

Alfred von Tirpitz (Wikimedia Commons)

Bear in mind these were solely the aims of the German power elite, not the mass of the German people. As far as domestic aims were concerned it was the expectation that a German victory would enable the power elite to make the constitution even more reactionary, so that any hope of the working class to participate in government in the future and exercise a moderating influence on policy would be illusory.

The above assessment was advanced by Fritz Fischer some fifty years ago. It is still being discussed, as the conference at the German Historical Institute in London in October 2012 bore witness. The research of the intervening years has merely fine-tuned various aspects or quarrelled with terminology. It is, therefore, curious why some high profile historians, such as Niall Ferguson, Sean McMeekin, Chris Clark and Margaret Macmillan have, so it would appear, chosen not to take Fischer on board.

Finally, the German means of pursuing these war aims, both on land and at sea, made evident first by the mass execution of Belgian civilians and later by indiscriminate submarine warfare, has earned the Reich the appellation of a ‘rogue state’, that is, one which operated in total disregard for international law. If it was not that, it was the matrix out of which the criminal regime of Adolf Hitler emerged. The continuity of the Second Reich into the Third Reich is laid bare.[4]

* Reverend Dr John A. Moses is a historian of Germany and Europe and an ordained Anglican priest. This short discussion paper was delivered in a forum on conflict at the Australian Historical Association meeting at the University of Queensland, July 2014. A longer paper covering similar ground is here.

[1] The Theory and Practice of History by Leopold von Ranke, edited with an introduction by Georg G. Iggers and Konrad von Moltke (New York & Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill , 1973, 97.

[2] See , Ernst Simon. Ranke & Hegel Beiheft 15 der Historischen Zeitschrift, 1928.

[3] Moltke: Leben und Werk in Selbstzeugnissen: Briefe, Schriften, Reden selected and edited by Max Horst (Birgsfeld bei Basel: Verlag Schibli-Doppler, no date), 351. In a letter dated 11 December 1880 to the Heidelberg professor of international law, Dr Johan Kaspar Bluntschli (1808-1881) who had sent Moltke a handbook of the Institut für Völkerrecht , entitled Les Lois de la Guerre sur la Terre, for comment. It is significant that Bluntschli was Swiss and a proponent of international peace. He was founder of the Institute for International Law at Ghent.

[4] John Horn and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities 1914: A History of Denial (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001; Alan Kramer, Dynamics of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War, Oxford: OUP, 2007.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.