Barbara Carol Heaton*

‘A history of unrest and turmoil: coal miners during World War II’, Honest History, 4 August 2015

Controversy continues over the role of militant unions in Australia during World War II. While the sharpest focus has been on the wharf labourers there has been little response to the accusations against coal miners.

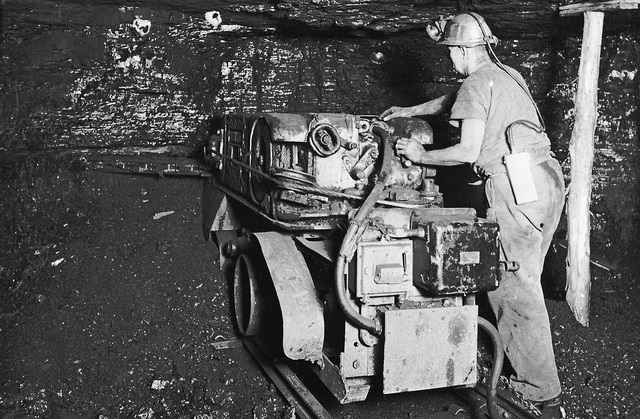

Miner working at the coal face, Lake Macquarie, NSW, 1946 (Flickr Commons/Norm Barney Collection, University of Newcastle)

Miner working at the coal face, Lake Macquarie, NSW, 1946 (Flickr Commons/Norm Barney Collection, University of Newcastle)

It is true that coal production decreased and time lost to strikes increased throughout the war. Although it was Miners’ Federation policy to fully co-operate until the end of the war, coal output declined steadily from 12 ¼ million tons in 1942, to 11 ½ million in 1943, 11 million in 1944, and just over 10 million tons in 1945. In 1942, 177 656 working days were lost through strikes, in 1943, 326 231, and in 1944 over 300 000.[1] However, the reasons for these figures are unexamined or distorted by some observers and simply misunderstood by many others.

Phillip Deery wrote that, for centuries,

neglected and forgotten by society and ruthlessly exploited by the owners, coal miners acquired attitudes and patterns of behaviour that were unique in working class history. In the coalmining industry each new generation carried with it legacies of bitterness and conflict. The history of industrial relations was therefore one of unrest and turmoil, with the strike weapon used frequently. This high strike propensity can be fully explained only by taking into account the total environment of the coal miner – the nature of his work, and the type of community in which he lived.[2]

In New South Wales, mine owners and operators showed scant regard for the health and safety or general well-being of the miners; their motto was a simple one, ‘profit before people’. No health and safety measure was ever initiated by the owners; the owners were forced to implement these measures by union action, industrial court decision or government legislation. Inquiries in the 1930s and 40s show that many deaths and injuries could have been avoided if owners had fulfilled their obligations to supply safety equipment.

Mine safety could have been dramatically improved if employers had sought this goal. Owners, however, let the injuries recur rather than meet the extra cost. They argued that miners would neglect equipment that cost them nothing thereby neatly explaining their own carelessness with lives whose moral significance was not registered in accountants’ ledgers.[3]

Exact numbers of work fatalities have never been available for the northern NSW coalfields, by far the largest and most influential mining area in the country, but almost half of the more than 1800 identified deaths etched on the Comerford Memorial Wall at Aberdare occurred between 1900 and 1950. A NSW miner who worked for 40 years between 1902 and 1976 had a one-in-24 chance of accidental death and a one-in-five chance of serious, debilitating injury.

The families of the northern NSW coalfields were politicised by the conditions under which they and their families lived, worked, and too often died. They lived also with the broader community’s indifference to their circumstances. Yet mining families displayed great self-reliance, developing services and cultural activities unequalled in any other region in the country. Through union levies they hired their own doctors and paid for local hospitals, ran friendly societies providing sickness and funeral benefits, had well-stocked libraries and evening classes at the schools of arts, supported top sporting teams, bands, choirs and a symphony orchestra, and established co-operative stores which sold all the basic necessities of life, returned profits to their local members, and, most importantly, provided credit during strikes and industry down-turns.

Elections for union leaders were held annually and communists held key positions from the 1920s. The rank and file, even if not communists themselves, voted for these men, who were held in high regard by the majority. When the men were accused of being no more than dupes of the communist leadership it was counter-productive as well as inaccurate. Barry Swan, former General Secretary and leading Miners’ Federation representative for almost 30 years from 1970, provided this perspective: [4]

NSW coalminers [during this period] did not have to be educated by the CPA [Communist Party of Australia] to know that the needed improvements in the workplace environment of coal mining in terms of conditions and wage rates was well overdue … While the processes involved in obtaining the improvements being sought enjoyed the benefit of good leadership (irrespective of the mix of ideology at the top level at any given time) it was the militancy in Common Cause [the Miners’ Federation’s then weekly journal] from rank and file members that was the most significant element in every successful battle waged.

Over the years the men voted against the Central Council (national and district representatives) recommendations on a number of significant issues. Allegiance to the communists never transferred to parliamentary elections, where the percentage vote for ALP candidates was the highest in Australia. It was a practical not ideological loyalty for the vast majority, who were influenced in union elections by the fact that, as Swan said, ‘among its [CPA] membership were some of the most dedicated and gifted orators the Australian union movement has ever produced, men capable of advocating strongly and convincingly for their cause’.[5]

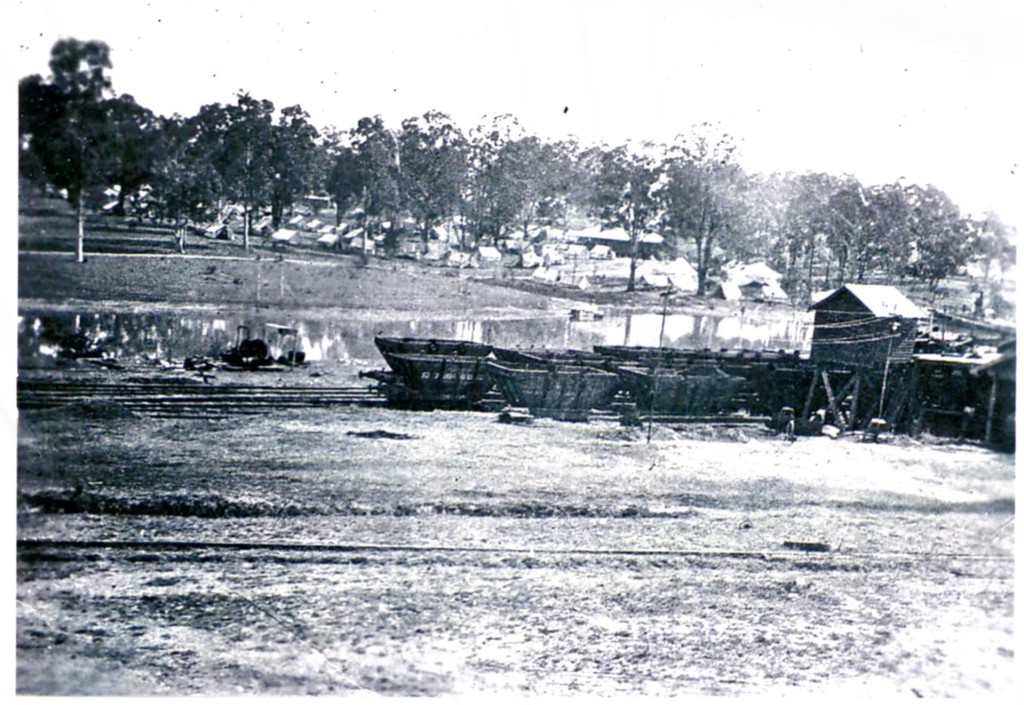

Police encampment, Rothbury, 1929 (Edgeworth David Museum, Kurri Kurri; previously unpublished)

Police encampment, Rothbury, 1929 (Edgeworth David Museum, Kurri Kurri; previously unpublished)

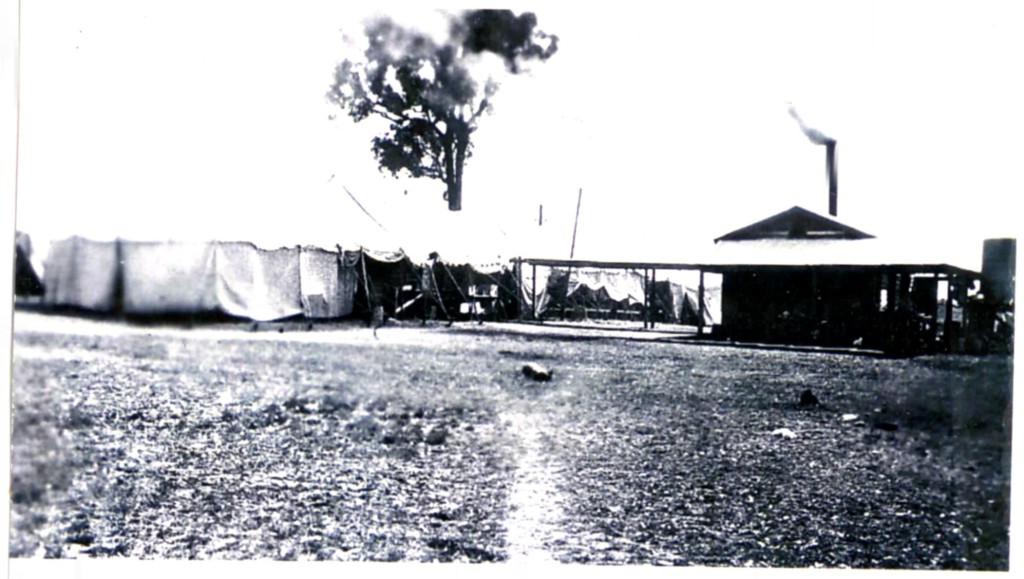

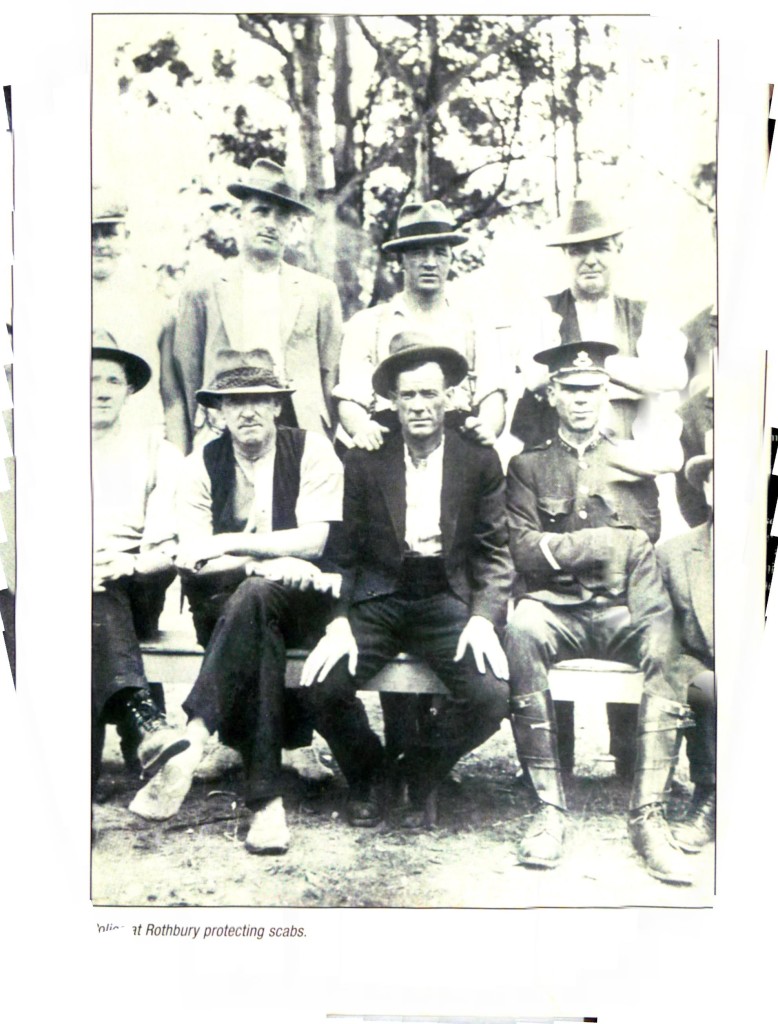

Scabs and police, Rothbury, 1929 (At the Coalface, CFMEU)

Scabs and police, Rothbury, 1929 (At the Coalface, CFMEU)

In 1940 over one thousand miners were still unemployed after the hard years of 1920s and 1930s, which were marked by complete shutdowns and short working weeks. On the northern NSW coalfields, which employed three-quarters of the country’s more than twenty thousand miners, most were veterans of the infamous 1929-30 lockout and what became known as ‘the Rothbury Riot’ when men were shot and wounded by the police at the Rothbury mine. This was followed by fifteen months of terror by the police ‘basher gangs’ sent by the conservative NSW government, and near starvation which drove the men back to work. The federal Labor government had refused to prosecute the mine owners, despite a court ruling their lockout of the men was illegal. The mining communities remembered the betrayal; among them were bitter and disillusioned World War I veterans.

First elected to office during the war while still in his twenties, Jim Comerford was a teenage veteran of the lockout, a communist and a political activist during the Depression. He had a 35-year career as a leading official in the miners’ union, then was widely known and respected as an historian, social justice advocate, writer, book reviewer, and recipient of community and academic awards and honours. Papers held at the Edgeworth David Museum at Kurri Kurri contain his personal reflections on union campaigns and the actions and character of various key participants during that time.[6]

Jim Comerford in later years (Sydney Morning Herald)

Jim Comerford in later years (Sydney Morning Herald)

A protracted campaign had started in 1937 for a return to pre-lockout wage rates and improved conditions, leading to a lengthy strike in 1940 affecting many thousands of workers whose industries depended on a supply of coal. Determined industrial action had gradually won the miners many of their claims, including a 40-hour working week, paid holidays, supply of individual safety equipment, and recognition of work-related lung diseases under the Compensation Act. At every stage, implementation of the Arbitration Court decisions had been delayed and frustrated by the mine owners’ tactics. One of the owners’ representatives told a coal industry judge in 1937 that the industry could never be regulated because miners were different from other people. They may have been but not in the demeaning, self-serving sense used by the bosses.

At the time of the strike in 1940 the USSR was a signatory to a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, heightening suspicion among Australian politicians and the broader community about the commitment of the senior mining union leadership to the war effort. At the same time, inside the union, factions opposed to these communist officials sought to undermine their credibility.

At the height of the 1940 strike a letter was distributed at night to miners’ letterboxes to be read on Anzac Day. Purporting to come from William Orr, then general secretary of the union, it provocatively stated the aim of the strike was to keep going ‘until every industry in Australia is tied up’, effectively ‘sabotaging the Menzies Government’s war schemes … This is the workers’ bid for real power. We are demonstrating our strength and the governments are powerless to move. We defy them to take action.’ [7]

The letter referred to the revolution in Russia and how the miners’ leaders were prepared to ‘take up the struggle with arms’ like those comrades had done. Comerford kept a copy of the letter and his handwritten comments identify the letter as a fake, put out by ‘those who were later identified with ALP Industrial Groups’.[8]

In the week prior to this event Prime Minister Robert Menzies came to the coalfields to speak at public meetings urging an end to the strike and a return to arbitration. Arrangements backfired when it was announced that Menzies’ address to the men at a local cinema would be broadcast on national radio with Menzies as the only speaker allowed. When that news was revealed, Comerford recalled in 1978, ‘No Jericho trumpet could have levelled the wall of support for the strike which was flung up by those headlines’.[9]

After a demonstration outside the cinema the miners and their supporters moved to the football ground, where they held their own meeting. To his credit, Menzies joined the thousands of people there but was told he would have to wait his turn to speak. Leaders Bill Orr and Bondy Hoare, both known for their great oratory skills, spoke of the current situation and their mistrust of the arbitration process. Then Menzies, says Comerford, ‘let loose all his great platform skills. He kept at us about the war and stirred our unease about that and our immediate situation … with the force of that superb technique.’[10]

Changing tack, Menzies then launched an impassioned attack on Bill Orr and his position as a communist. ‘The crowd erupted. Most of them stood aside from his [Orr’s] politics but they had a deep affection for him because of his great ability and integrity. The rest of the meeting became an anti-Menzies demonstration.’[11] In the following month, the Menzies government’s banning of the CPA was overturned by the ALP government following Nazi Germany’s invasion of the USSR.

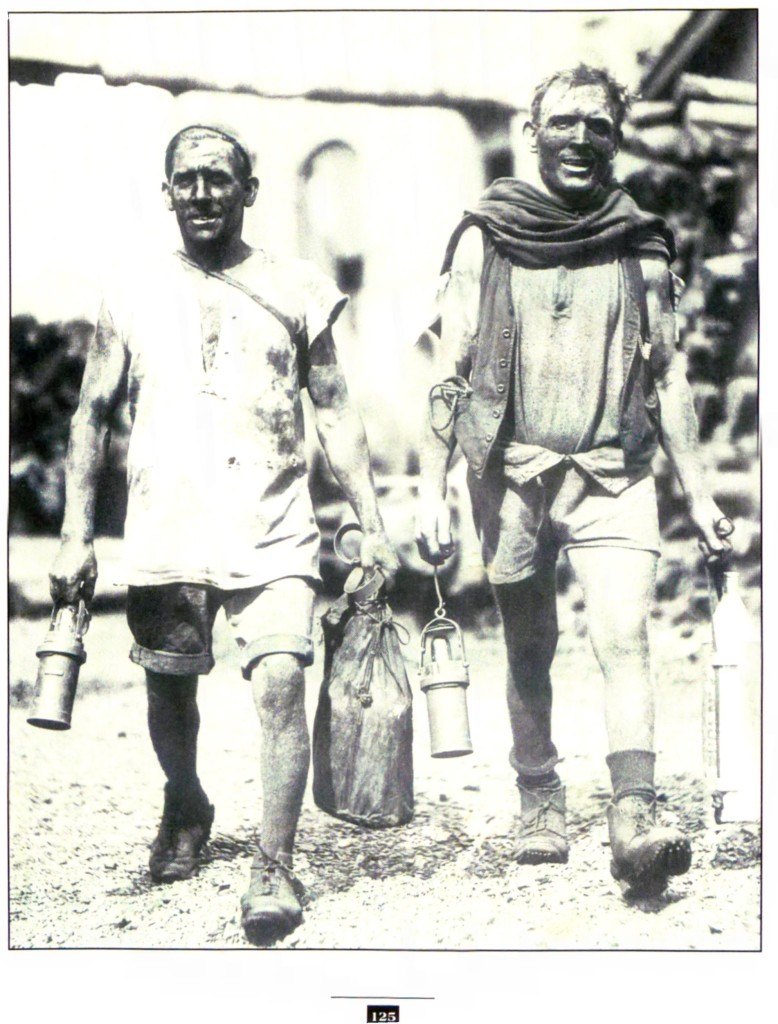

Miners, Northern NSW fields, 1930s (At the Coalface, CFMEU)

Miners, Northern NSW fields, 1930s (At the Coalface, CFMEU)

A significant group in the union whom Comerford wrote about were veterans of World War I.

Strangely … it was never easy to get dedicated support [from the veterans] for the war effort. Cursory support, Yes! But based more on the cold logical need for support with the Japanese as close as New Guinea. But with none or little of the anti-fascist fervour of those on the Left.

Many of the ex-service miners … had served in NZ or Canadian conscript armies as well as Brit. conscripts. Been through 1921 coal lockout and 1926 general strike [in Great Britain] as well as some long near starvation days on the unemployed lists. From being war-time heroes fighting for high ideals they had become social rejects, attracted to revolutionary subversion.

But emigration not revolution was embraced to provide an escape from a Britain that failed to offer them or their families any prospect of a reasonable future. Another element in the fabric of the Coalfields society were Australian born miners who had served in 1914-18 war many of them Gallipoli men. They were in the main just as bitter as anyone else not only about the war but so much more that they had been put through.[12]

Among the union leadership there was a strong belief, especially after Russia joined the allies, that the war must be won. They made unprecedented efforts to get the rank and file to support this position. A union congress in February 1942 ‘declared full support for the war against fascism’. Regulations were accepted providing for industrial conscription. ‘The freezing of wages and rationing of goods were accepted, support extended to war loans and an advisory panel set up with trade union representation. In return, the Government accepted the principle of compulsory unionism.’[13]

The union leadership’s frustration with the response of many of its members to what they perceived as these draconian measures was clearly demonstrated in an uncompromising letter sent, after an extraordinary convention of the union in 1943, to every member of the union in the northern district. The letter pointed out that the men had the important task ‘to ensure the adequate flow of the weapons necessary to protect Australia by producing coal, the only power available for use in our war industries’. This was followed by a graphic description of what could be expected if the Japanese successfully invaded Australia, as they had invaded throughout the Pacific. The letter set out the rules for dealing with a dispute or stoppage that could interrupt production and the fines that would be imposed on those who did not strictly follow the rules.

Women’s auxiliary demonstration, Sydney, May Day, 1941 (At the Coalface, CFMEU)

Women’s auxiliary demonstration, Sydney, May Day, 1941 (At the Coalface, CFMEU)

The letter reminded the men that the Curtin government had done a good job in ‘uniting Australia and providing defence for its people … but would bring down Regulations to improve the Coal Industry’. So the union leadership arrived at a ‘code of rules whereby the Federation itself would discipline members’.

It is alleged by many of our members [the letter ended] that the boss is responsible for many of the stoppages. With this we entirely agree, yet despite this we urge every member to continue work and carry out this policy, and we assure you, that no stone will be left unturned to put some of these people where they belong, if they do not play the game.[14]

Comerford was one of the Board of Management members who signed this letter.

In some undated notes written many years later Comerford acknowledged that

it was not easy to get rank and file support for the official policy of the union … In fact, distrust of authority and the upper echelons of our society was a common feeling among these men and their women folk. They were cynical about the war-time appeals made to them by those same authorities who between the wars had compounded their hardships and sufferings and who by every stratagem and device available to them had resisted any legitimate claim for improvement of their lot. The moods of cynicism and bitterness were only heightened by the unscrupulous miner bashing promoted by the less responsible newspapers like the Sydney Daily Telegraph.[15]

Edgar Ross, editor of the Miners’ Federation journal, Common Cause, summed up the wartime position:

Even if scepticism could be overcome there were other important factors in the situation … The mineworkers had many grievances … and the inclination was to press for their rectification. Many owners, too, were loath to change their traditional approach of “fight it out” … Even more influential was the factor of the technical backwardness of the industry. It was ill-equipped to meet the demands now placed upon it.[16]

Amid this volatile mix sat a section of the coal owners, some linked to the anti-Labor United Australia Party. This group sought to undermine the Labor government and split the Labour movement. In an unfinished article titled ‘The Spy-Pimps of the Coalfields’, Comerford discussed attempts to undermine Northern District President Henry Scanlon during World War II, then went on:

About this time a new but small formation was established. It called itself Northern Collieries Pty Ltd. It was very publicly pushed by its secretary H. Gregory Foster. Clearly HGF wanted his association to represent all coal owners. He failed … HGF could muster only a few mines most of them small, who had stood outside the Coalowners’ Association … Despite the smallness of H.G.F.’s association he made more anti-union noise than the rest of the Northern, Southern, Western coalowners put together.[17]

At the same time as the attacks on Scanlon ‘copies of an extreme Right Wing monthly published by the British Empire Union were mailed to the home of every Australian mineworker’. Bill McBlane, the ‘most respected of all unionists’ told Comerford ‘that HGF informed him that he had agents inside the union who kept him informed about the activities of the Left Wing’. They succeeded in defeating Scanlon in the next election ‘and the anti-Scanlon vote was mustered from elements who would go around saying “the country could not be worse off if the Japs did run it”. Names can be named.’[18]

In a typewritten essay titled ‘The Miners’ Federation and the War’, prompted by the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, 82-year-old Comerford recalled that the union leaders’ efforts to improve production and lessen unauthorised stoppages

were blunted by hysterical attacks from sections of the Establishment media, the Menzies opposition, from provocation by some not all coal owners. They were aided by a varied grouping of elements from inside the Federation. Though not all of those who had reservations about Federation policy could be regarded as being unprincipled. Many ex-servicemen from the 1914-18 war and thousands of miners who spent up to nine years on the dole were cynical about how quickly masses of money became available for war as against their near starvation during the Depression …

So long as communist union leaders could be humiliated and defeated any consideration about improving miners’ working and living conditions did not matter. The bosses media as well as conservative parties hailed those people as “moderates”. During the war they went into reverse and became “militants”. They harnessed every dubious element they could to support their disruption …

The constant battle by Federation leaders against disruption caused the bitterly anti-union Daily Telegraph to say that the party pots in Canberra were being cooked over coal and to call the miners the spoiled children of industry.[19]

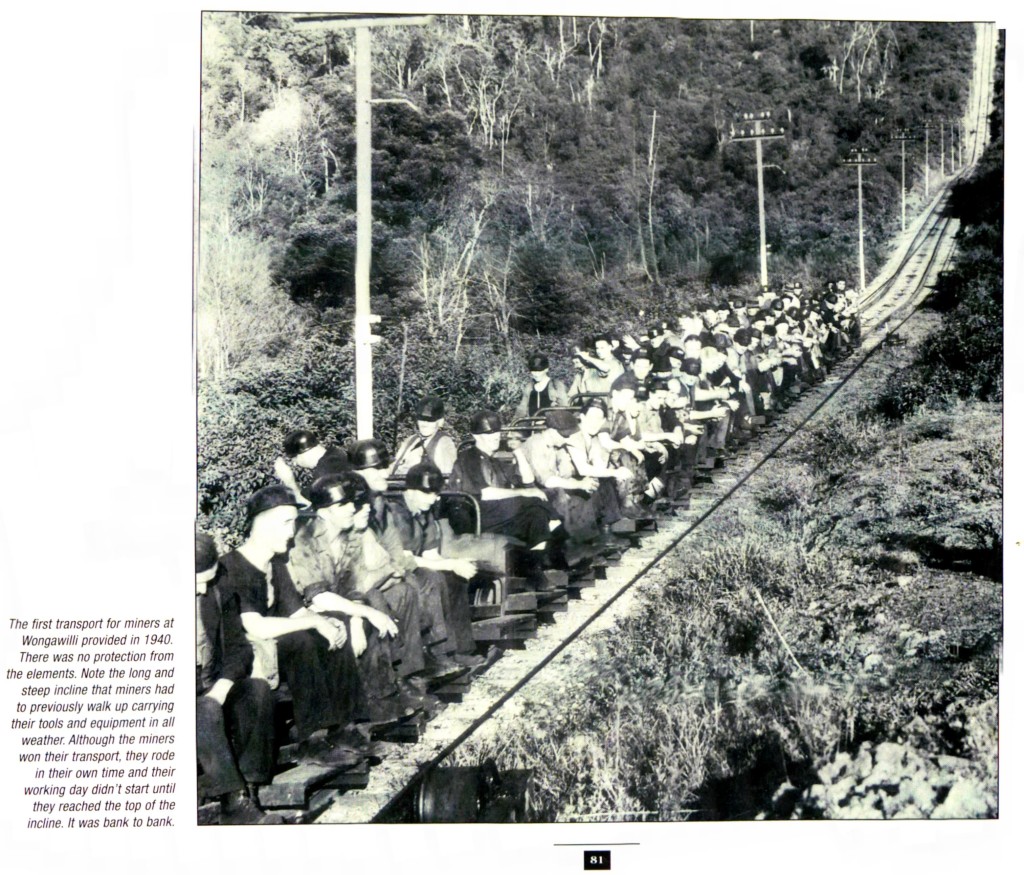

Miners on inclinator on their way to pit top, 1940 (At the Coalface, CFMEU)

Miners on inclinator on their way to pit top, 1940 (At the Coalface, CFMEU)

This attitude was encouraged by those whom Comerford identified as ‘members of the Coalfield ALP branches and amongst the fiercest opponents of their own government and Federation support for that government. It was evident that … it was more important to seek the elimination of Communists from the leadership and governing bodies of the Miners’ Federation than it was to support the war effort.’[20] This was a foretaste of the struggle within the ALP, with the escalation of the activities of the Industrial Groups and Catholic Movement, to eliminate CPA leadership from the militant unions.

Mine owners and managers exacerbated the situation by using pressure to produce more coal, using methods that hardly changed over the previous century, as well as by violating award conditions and harassing the miners. The union leadership had themselves maintained a strong opposition to mechanisation without compensation, because of the loss of jobs that would come with it, and the owners were often unable or unwilling to finance it.

Evan Phillips, President of the Miners’ Federation during the 1970s, looked back:

One of the things I found significant during the war years was the lack of co-operation by the companies. Prices were pegged, wages were pegged, company tax was high and the government regulations were strict on companies. But there was this attitude that the government should look after the war and let the companies look after wages, prices and profits. The companies were looking for profiteering and black marketing and the rest of it and when they couldn’t get their way they became unco-operative.

The press was forever needling the government and they made an issue of coal miners, because during the war in Australia (as in Britain) private coal companies let the nation down in its hour of need because they couldn’t supply the coal the nation required. And they blamed the miners for it. The press picked this up, so the miners became a sort of whipping post during the war years. The companies weren’t prepared to break the law, because of course they’d feel the weight of it and the government on their necks. But they were prepared to instigate and did, a great deal of hostility in order to try to get their own way by putting pressure on the government. The miners became victims of it, so there was quite a struggle at that time to try and resolve disputes with reluctant companies and to keep mines working. A lot of times discussions with the management, the local management itself would be jammed between the miners attitude to the dispute and company policy.[21]

Prime Minister Chifley confronted by coal miners, NSW, 1949 (Flickr Commons/Chifley Research Centre/John Faulkner)

Prime Minister Chifley confronted by coal miners, NSW, 1949 (Flickr Commons/Chifley Research Centre/John Faulkner)

Throughout the war the federal Labor government, having tried a conciliatory approach to the miners and appeals to their patriotism, became more frustrated, angry and accusatory towards them, all to no avail. The figures for declining production and increased stoppages were clear evidence that a productive truce between the miners, owners and government never eventuated. By the end of the war an increase in accidents, exhaustion and the struggle to discipline growing recalcitrant elements of the union forced its leadership to focus on a post-war program to redress their long-standing grievances. It would be the 1950s, with the introduction of mechanisation and better wages and conditions, before there was any marked improvement in figures for production and stoppages.

* Barbara Heaton is a retired public servant, a graduate of the University of Newcastle, and has contributed to a number of publications focusing on the history of Newcastle and the Hunter Region, most recently a chapter on the 1949 coal strike for Radical Newcastle. She is currently preparing a biography of mining legend Jim Comerford.

[1] Robin Gollan, The Coalminers of New South Wales: a History of the Union 1860-1960, Melbourne University Press, Parkville, Vic., 1963, p. 225.

[2] Phillip Deery, The 1949 Coal Strike, <LaborHistory. org.au/view document/168 .

[3] Andrew W Metcalfe, For Freedom and Dignity: Historical Agency and Class Structures in the Coalfields of NSW, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988, p. 62.

[4] Email message to the author, dated 15 March 2014.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Notes held in Jim Comerford Collection at Edgeworth David Museum, Kurri Kurri. There are several filing cabinets with copies of typed letters, articles, and book reviews published by Comerford, along with handwritten notes, mostly undated. Before moving house for the last time and transferring his collection to the Museum, Comerford culled the documents. Unfortunately, the collection has only been superficially catalogued and indexed due to time constraints on the dedicated volunteer staff.

[7] Copy of letter dated 24 April 1940, Comerford Collection, Kurri Kurri.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Comerford, Newcastle Morning Herald, 7 June 1978, pp. 16-17.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Comerford, handwritten notes headed ‘WORLD WAR 2 JAPS ARE PRODUCING MORE COAL THAN WE ARE’, Comerford Collection, Edgeworth David Museum, Kurri Kurri.

[13] Edgar Ross, A History of the Miners’ Federation of Australia, Australasian Coal and Shale Employees’ Federation, Sydney, 1970, p. 388.

[14] Copy of letter prepared by union leaders after convention in May 1943, Comerford Collection, Kurri Kurri.

[15] Comerford Collection, Kurri Kurri.

[16] Ross, p. 385.

[17] Comerford, The Spy-Pimps of the Coalfields, Comerford Collection, Kurri Kurri.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Comerford, The Miners’ Federation and the War, Comerford Collection, Kurri Kurri.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Evan Phillips, quoted, Fred Moore, et al., At the Coalface:the Human Face of Coalminers and Their Communities: an Oral History of the Early Days, Mining and Energy Division of the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU), Sydney, 1998, p. 110.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.