‘This white hot flame burned bright’, Honest History, 19 May 2018

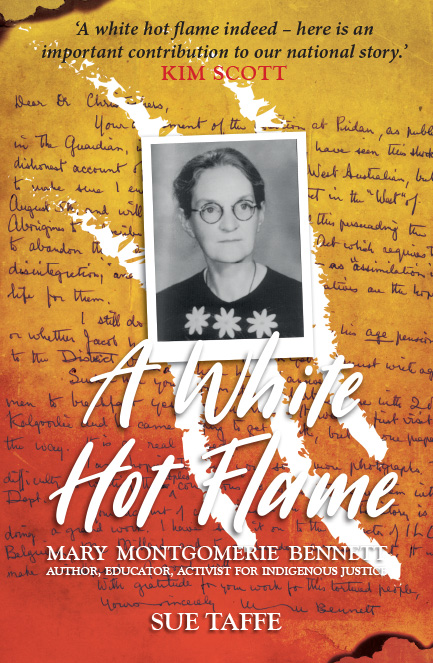

Pamela Burton reviews A White Hot Flame: Mary Montgomerie Bennett – Author, Educator, Activist for Indigenous Justice by Sue Taffe

This well-researched biography of Mary Montgomerie Bennett (1881–1961) is a must read for those interested in Australia’s real history; it provides a clear window into Australia’s colonisation by white settlers. Sue Taffe gives a compelling account of this under-recognised woman, Mary Bennett, whose thinking about, perceptions of, and solutions to the inhumane treatment of first Australians were all far ahead of her times.

Bennett was a member of a successful squatting family. Her radical thinking and her lifetime devotion to advocating for Aboriginal land rights and full human rights as equal Australian citizens is the more remarkable, given her description of her younger self as a ‘shocking imperialist’. Taffe’s research into Bennett’s childhood and her parents’ backgrounds and life-stories identifies various influences that drove Bennett to love and understand the Aboriginal peoples she came to know.

Bennett was a member of a successful squatting family. Her radical thinking and her lifetime devotion to advocating for Aboriginal land rights and full human rights as equal Australian citizens is the more remarkable, given her description of her younger self as a ‘shocking imperialist’. Taffe’s research into Bennett’s childhood and her parents’ backgrounds and life-stories identifies various influences that drove Bennett to love and understand the Aboriginal peoples she came to know.

Bennett spent the best part of 30 years writing about her Scottish father, Robert Christison, in a biography titled Christison of Lammermoor; she was intent on having his success as a pioneering pastoralist remembered. Christison emigrated to Queensland as a land speculator and established a pastoral station in the 1860s.

Taffe’s work includes an in-depth analysis of Bennett’s telling of her father’s life. This reveals not only Bennett’s love for and admiration of her father, but also her having to confront, as her research progressed, the reality that the success of Queensland pastoralists, her father included, emerged from violent frontier wars. ‘This realisation’, Taffe says, ‘was the beginning of Mary Bennett’s conflicted identity as she strove both to exonerate her father from any wrongdoing and to influence the white majority who seemed to accept frontier violence as inevitable’. In Taffe’s view, Bennett seemed ‘unwilling or unable to face the likelihood that her father was involved in violent altercations with Aborigines on the frontier’.

Bennett might not have witnessed any ill-treatment of Aborigines by her father, as she spent most of her childhood away from the remote property, living instead in less remote smaller Queensland communities and in London, her mother’s choice of residence. Bennett was nearly 12 years old when her mother and younger siblings returned to Australia to live on her father’s station, ‘Lammermoor’. While there, she learned that the Dalleburra people, on whose traditional land Lammermoor was developed, held a quite different world view from the ‘imperialist’ perspective of the Christison family.

Taffe follows Bennett’s life as a teacher, writer and advocate for justice on behalf of Australian Aboriginals. One might suspect that Bennett had a need to assuage the guilt she felt at having lauded her father’s innovative activities as a squatter, knowing that profits reaped by pastoralists were made on the backs of the people who were the original occupiers and arguably the owners of those lands. Bennett’s second book, The Australian Aboriginal as a Human Being, confronted, as its title indicates, the contemporary prejudicial view that the Aboriginal ‘race’ was inferior.

After the death of her English husband, Bennett in her forties returned to live in Perth and, from the 1930s onwards, she brought to the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization her concerns about the prejudicial and ignorant ill-treatment of Aborigines. Taffe notes that Bennett preceded former Prime Minister Paul Keating in talking about our failure ‘to imagine these things being done to us’, Keating’s words so many decades later echoing hers.

Although Bennett has been described as a feminist, she fell out with Perth feminists when they failed to oppose the removal of Aboriginal children from their mothers. Bennett’s passion about this issue is explained by Taffe’s moving account of a tragic story about Bennett’s ‘adopted’ Aboriginal sister, Jane Gordon. Pale-skinned and filthy, Jane, accompanied by a woman – Maggie, who Bennettt’s mother described as an Aboriginal ‘opium drunkard’ – came begging for food at the Lammermoor kitchen door.

Mrs Christison took Jane in. The child’s Aboriginal mother, Judy, had been in hospital and, once discharged, she came to Lammermoor and told Mrs Christison that her daughter was the child of a Mr Gordon, manager of Yarrow Mere Station. Mrs Christison sought a permit to employ Jane, despite Jane’s youth. Because Mrs Christison and her children were leaving for England the following month, she also received permission ‘to take this half caste female out of the Colony’. It seems the intention was to provide the child with a home, not to employ her as a slave. Nevertheless, neither Jane nor her mother or family members had any say in the decision.

Dalleburra people, Lammermoor, 1892 (NMA)

Dalleburra people, Lammermoor, 1892 (NMA)

Jane didn’t cope well with the English winter and, falling prey to bronchitis, or so it was claimed, she was sent home by boat to Australia in the care of a stewardess. Robert, in a letter to a younger daughter, is reported to have written, ‘I hope that Jane has been sent away, she will be indeed a good riddance’; to his wife, he wrote, ‘I trust that Jane has disappeared for good’. And indeed, she had disappeared, so far as they were concerned. It upset Bennett that Jane was cast out of the family of which she had been a member for two years. Taffe found no more written or said about her by the family but her own research reveals a little of the difficult and rugged life Jane led thereafter.

Bennett’s fight for justice on behalf of her fellow Australians became her life focus. Notable women such as Ada Bromham, Jessie Street and Shirley Andrews were keen to exchange and publicise information about her. Taffe traces the efforts of these women to unearth the archives on Bennett’s life and work. However, it would seem that Bennett had become the enemy of governments, and that of Western Australia in particular. The establishment did not want her work remembered or acknowledged. Taffe has changed that.

* Pamela Burton is a Canberra lawyer and a committee member of Honest History. For Honest History she has reviewed Annabelle Brayley’s Our Vietnam Nurses and Sharon Bown’s One Woman’s War and Peace. She has also written about being an independent scholar and about her father, Dr John Burton (use our Search engine). She is the biographer of Mary Gaudron and has written about the Waterlow killings and published a novel.

Hi Crea8tive: for more info, suggest you contact author Sue Taffe through the publisher Monash University Publishing or through Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, where Ms Taffe is an Associate.

Jane Gordon is my great great grandmother, she remained in QLD (as far as I’m aware) and ended up marrying a man called Octavious Lenoy. They had many children together. Unfortunately, Jane and her children also ended up being part of the stolen generation. She had a tough life. I never did meet Jane (We call her Janie) but would love to know more about her. I have read the physical letters written by Mary Christison in regards to Jane living with them but have not seen the ones from Bennett stating that they were glad to get rid of Jane. Is there somewhere that I might be able to find this? If you have any other information about Jane, I would also love to hear about it. Thanks kindly. 🙂