Buch, Neville

‘Why this war in this way? A note on the Great War’, Honest History, 28 August 2014

The question of whether World War I can be justified, either at the time, or looking back now, has overshadowed the failure – and inability – to challenge how the war was actually fought. After-the-event criticism of particular campaigns in the war is not new, and dissenting views during the war were suppressed, but the connection between militarist justifications of war, on the one hand, and the ability to challenge military decision-making during the war, on the other, has not been explored in Australia as well as it could be.

Certainly, at this stage of the Great War commemoration these questions are being played down. This is wrong. Ordinary members of the community should have access to a wider historiographical understanding of the war, rather than being catapulted into isolated debates about single features – entry, Gallipoli campaign, conscription, and so on. I am particularly concerned that, by 2018, the commemoration will so exhaust historical interest among members of the community that they will resist focusing on the critical questions of the military failures that led to the stagnation into total war and to the inconclusiveness of the peace process which followed.

Turkish heroes from Lone Pine, 1915 (Flickr Commons/Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office)

When we ask the question whether World War I was a ‘just war’, the answer is usually that the British Empire, including Australia, needed to confront Prussian militarism. But the question of whether the war was justified, for this or any other reason, cannot be left as the only abiding and significant issue. The conduct of the war should also be a paramount question. That the war was allowed to degenerate into total warfare with extremely little regard to the value of human life is a far more significant matter than striking an academic balance between the various putative reasons why the war commenced.

British imperial militarism only differed from the Prussian variant in that it was more constrained – and in that sense shaped – by social and liberal democratic forces. Militarism, however, is still militarism, regardless of the language in which it is couched. Militarism is based on the falsehood that a man’s virtue (and it was gender specific) is affirmed by his making ‘the ultimate sacrifice’ for his country or in his bravery on the battlefield. In the militarist view, there are no other important considerations which can mitigate such duty.

What has confused people, then as now, is that what is offered up in arguments about sacrifice is an ethic for service, not a justification for war, or for carnage, slaughter and devastation. It fails to address what really are the critical matters: why war? why this war? and very importantly, why war in this way?

An insight into that failure is seen in the way the popular phrase at the outbreak of war, ‘last man and last shilling’, has been heard and read as an expression of loyalty. There is almost no comment or thought that this remark expressed something even more demanding than a call to duty or service. It is an absolutist call. While the dissimilarities of statehood and ideology are noted, the imperial absolutism of 1914 is very little different to what we are now seeing in the extremism of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

British imperial militarism was only different from its German counterpart because of the nature of British democracy at the time. By contrast, democracy was very weak in Germany. British democracy allowed anti-war voices to exist and to ask those critical ‘why?’ questions. Hence, the British imperial form of militarism could never be as strong as the Prussian version.

Even so, what is concerning about the history of World War I in the British Empire is the lack of criticism – in Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, or anywhere else – about the conduct of the war. As happens with many major wars, there was a mental switch which turned off once the initial question of justifying the war had been addressed. Furthermore, government forces did everything in their power to suppress dissenting voices on the war.

All of this meant that there was very little opportunity during the war to comprehend and publicly discuss that something terrible was happening in relation to the conduct of the war. Yes, there was overwhelming evidence in the casualty lists and the loss of loved ones. However, that got translated into the debates about conscription. Although the debates on that issue were particularly intense in Australia, they did not carry over at the time into significant criticism of military decision-making.

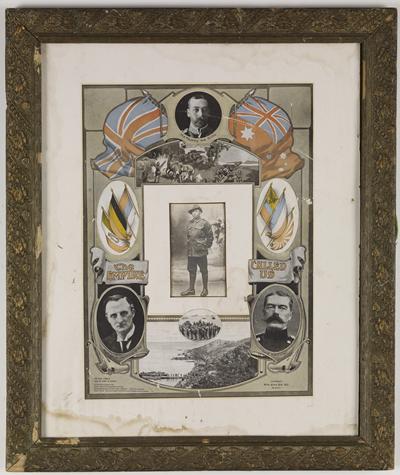

Certificate of Appreciation ‘The Empire Called Us’, c. 1918 (Museum of Victoria, Numismatics and Philately Collection). Those pictured are the King, Grey, Kitchener and an unknown soldier.

This is an important point to make because we have come to understand, after the event, that the reasons for the great slaughter of World War I came down to the stubborn refusal to change overall military tactics or to decide upon a ceasefire until far too late. Yet, national socialists in Germany, led by Adolf Hitler, would come to argue that the ceasefire was not late enough; they had wanted the war to keep going.

That is the pertinent point. The ‘stabbed-in-the-back’ thesis that the German Reich promoted in subsequent decades was based on their commitment to total war, a commitment Germany could not carry out in World War I. The Allied forces in World War I, through their own conduct of the war, their commitment to total war, played the ‘Prussian’ militarist game better than the Prussians. This absolutist approach carried into the peace settlement and helped ensure that war would come again.

Neville Buch is a research consultant in history. He has a Ph.D., has done post-doctoral work, published several papers and is a member of the Professional Historians Association (Queensland).

The US Congress was similarly constrained in its reaction to the shocking actions of its own high command. On the morning of 11 November 1918, US troops were ordered to attack German positions – even though all knew the Armistice was to begin at 11am. As the US troops moved into No-man’s Land a German machine gunner climbed out of his position and gestured desperately for the US troops to go back. When the US troops continued to advance, he returned to his machine gun and commenced firing. Some 3000 US soldiers were killed in this attack. Some Congressmen were so outraged that they sought to sanction the US generals. Sadly no action as taken as the “Powers-That-Be” decided such action was inappropriate as everyone were celebrating the war’s end and “welcoming home the heroes from the War”. The commander of US Forces, General “Black Jack” Pershing was bitterly opposed to the Armistice, arguing the war should continue until Allied troops fought their way into Berlin. As always, war is too serious to be left in the hands of the generals.

Very well written and observed column.