‘Hell-Bent: Australia’s Leap into the Great War, by Douglas Newton, Scribe, 2014: Canberra Launch, Australian National University, 28 November 2014’, Honest History, 7 December 2014

There is a powerful myth concerning the way Australia behaves in international affairs. Great and powerful friends lead; Australia follows. On the road to the Great War, according to this view, there was some obscure diplomatic business in Europe which was then, as now, of little concern to Australia. Once Britain had declared for war – itself seen as more or less inevitable – it was equally inevitable that Australia would follow loyally. Labor’s Andrew Fisher – then leader of the opposition – is invariably quoted to the effect that Australia would fight ‘to the last man and the last shilling’. There was a rush to enlist, a journey to Gallipoli, and Australia’s Great War – its journey to full nationhood – had at last begun.

There is also a counter-myth, which two or three right-wing columnists at The Australian have taken responsibility for disseminating. From these writers, you would imagine that Australian policy-makers in 1914, having fully taken account of the strategic interests involved, took Australia to war in 1914 in a considered way. Their actions were guided by thoughtful recognition of Australia’s need to ensure that the Royal Navy rules the waves, and that Australia could continue to trade with the world. They were also concerned to uphold the values of British constitutionalism and Australian democracy against Prussian tyranny. From their account, you might imagine that the Australian government only took Australia to war after consulting the experts in the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre here at the ANU, possibly the Lowy Institute but, above all, the ultimate authority on Australia’s national interests, the commentariat at The Australian. Australia’s participation in the First World War becomes the first of many expressions of Australian alliance politics and foreign policy realism during the twentieth and early twenty-first century.

There is also a counter-myth, which two or three right-wing columnists at The Australian have taken responsibility for disseminating. From these writers, you would imagine that Australian policy-makers in 1914, having fully taken account of the strategic interests involved, took Australia to war in 1914 in a considered way. Their actions were guided by thoughtful recognition of Australia’s need to ensure that the Royal Navy rules the waves, and that Australia could continue to trade with the world. They were also concerned to uphold the values of British constitutionalism and Australian democracy against Prussian tyranny. From their account, you might imagine that the Australian government only took Australia to war after consulting the experts in the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre here at the ANU, possibly the Lowy Institute but, above all, the ultimate authority on Australia’s national interests, the commentariat at The Australian. Australia’s participation in the First World War becomes the first of many expressions of Australian alliance politics and foreign policy realism during the twentieth and early twenty-first century.

Douglas Newton’s Hell-Bent, although more concerned with the first of these myths, actually demolishes both of them. Australia did not follow Britain into the First World War. Rather, while there was still an anguished debate going on within the British Cabinet, Australia acted belligerently – and, it might reasonably be said, prematurely – by offering troops and placing the new Royal Australian Navy at the empire’s disposal. Douglas does not exaggerate the importance of Australia’s interventions – Australia did not start the First World War – but he shows that it was part of the background against which the debate was going on between the hawks and doves in Cabinet. It was an ingredient in the mix, and it helped the hawks, such as Winston Churchill, and undermined the doves, such as the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lewis Harcourt.

The diplomatic business going on in the European capitals, far from being obscure, was poised sufficiently delicately to have made those Australian offers an obscure footnote to history if Britain had remained neutral. Instead, because Britain entered the war, they became a headline to the disasters ahead at Gallipoli and the Somme.

But Douglas’s book also shows that there was something other than rational and realist calculation involved in Australia’s behaviour in 1914. There was a federal election campaign in progress in 1914, an occasion always likely to bring out the loyalist in everyone. But there is little reason to imagine that Australia’s leading politicians would have been any less enthusiastic in demonstrating their love of empire through offers of soldiers and ships if it had been political business-as-usual. Australia had federated in 1901, but it remained in its essentials a colony.

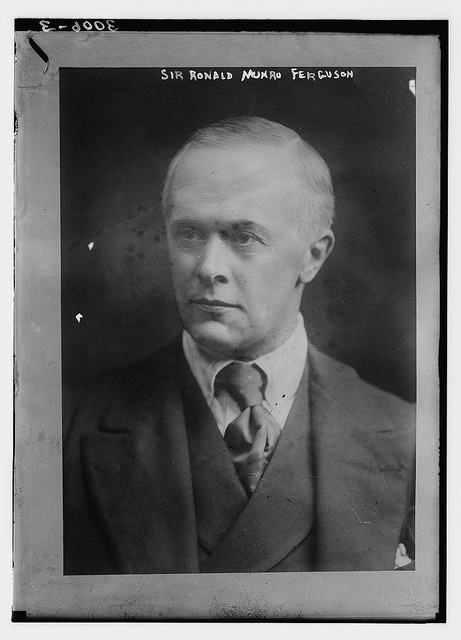

Here, I beg to differ from those on the left who want to argue that Australian nationhood was not made at Gallipoli because it had already been made at federation. One of many important and memorable features of this work is Douglas’s account of the instrumental role played by Ronald Munro Ferguson as governor-general in paving the way for Australia’s commitments; a governor-general’s role that in those days – in matters of war and peace, at any rate – combined that of a de facto high commissioner representing the British Government, leading figure in the Australian government itself, aristocrat among colonial plebs, and local manifestation of the magic and majesty of royalty. No wonder he was able to exercise influence so effectively when dealing with the likes of Prime Minister Joseph Cook.

One mark of a colony is surely a willingness to concede to others decisions about war and peace. Australia did that in 1914. And once war had broken out, as Eric Andrews showed over twenty years ago in his fine book The Anzac Illusion (1993), Australian politicians were almost entirely indifferent to matters of high strategy. These were debates for others – the same ‘others’ who had taken the decision for war in the first place.

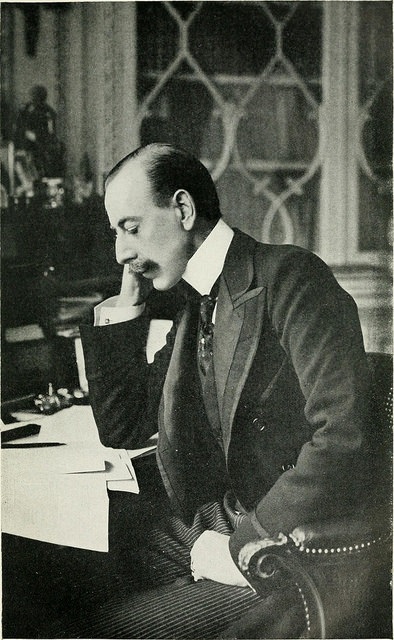

Lewis Harcourt c. 1911 (Flickr Commons/Newfoundland in 1911)

Douglas takes up in Hell-Bent matters that have been neglected in Australian historiography for about 75 years. The questions he asks, the sources he works with, and even the conclusions at which he arrives would have been perfectly intelligible to the likes of CEW Bean and Ernest Scott, the men who produced the official histories between the wars in the 1920s and 1930s – although as imperial patriots, they would surely have begged to differ.

In fact, it’s rather difficult to think of anyone between Scott and Newton who has taken up the matters dealt with in this book. When Australian history developed in schools, universities and the public sphere from the time of the Second World War – and especially from the 1960s – it was very little concerned with the matters Douglas takes up in Hell-Bent. The development of interest in the First World War, in which historians such as Ken Inglis and Bill Gammage played a leading role, coincided with the rise of social history or ‘history from below’. There was little space for the study of high politics, military strategy or diplomatic history. Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, there was another shift; away from the cabinet room, the chancery, military headquarters and the battlefield and towards the lives of ordinary people on the home front.

By the time I first encountered the ‘Australians in Wartime’ unit in the Victorian Higher School Certificate in 1986, you could study Australia in the First World War for several months without having encountered a single battle. Fromelles and Amiens were words that never passed the lips of the teacher. We did not even much study the Anzac Legend in those days. Nor, it should be added, was there any real sense of the First World War as an event in diplomatic history – the kind of treatment that Douglas offers here.

The rise of cultural history and memory studies initially had little appreciable effect on these trends. There was a gradual swing back to an interest in the experience of the ordinary soldier, but now he was reimagined not as the embodiment of certain national traits – as he had been constructed by Bean and, in a more qualified way, by Gammage – but as a site of bodily disfigurement and mental trauma. It is striking that work on the diplomatic and ideological contexts for the Australian Great War, when it appeared, came from scholars who were not specialists in Australian history or, at the very least, had begun in other fields. Neville Meaney at the University of Sydney springs to mind – he had come from United States history – and John Moses, a German specialist based for most of his career at the University of Queensland, is another scholar who has helped to shift Australia’s Great War back into the stream of European political and diplomatic history, where it surely belongs.

Douglas, of course, has come from German and British history to the subject-matter of Hell-Bent, and he brings to the task intellectual breadth, a meticulous approach to the sources, and literary gifts of a very high order. Henry Rosenbloom at Scribe would not have taken long to recognise that he had in front of him a manuscript that would speak to an audience well beyond the usual suspects – other academics and their students.

Hell-Bent also speaks to problems that are still with us; most fundamentally, the place of war-making in a democratic society. The world of 1914 is, in many respects, a foreign country. It’s hard to imagine an Australian government today offering up the lives of its young as recklessly as Douglas shows Australia’s decision-makers did for the sake of the Empire in 1914. Yet we live in a country whose government feels no obligation to permit the nation’s parliament to debate a commitment of Australian soldiers to a war zone. Democratic debate is still understood as dangerous – at least insofar as war and peace are concerned. Ordinary people cannot be trusted with foreign and defence policy; these remain matters for ‘the official mind’, such as it is in twenty-first-century Australia.

Douglas tells a story of manipulation and deception, still essential weapons in the armoury of governments that wish to take us to war today. In the four years ahead, these governments – in order to rationalise their actions in the present – will depend not only on manipulation and deception about that present; they will also work hard to spin the meaning of the past. We will hear much about the unbroken line of Diggerdom stretching from the Boer War through the two world wars down to Iraq Mark II.

Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson c. 1910 (Flickr Commons/Library of Congress)

Many books about Australian and the First World War will appear during these years, but few will be as important or as unsettling as Hell-Bent. Professional historians have a duty to unsettle – a critical role to play in disturbing the myths and ideologies that invariably sit behind political manipulation and deception. Douglas Newton’s Hell-Bent shows us just how much the old-fashioned virtues – conscientious research, intellectual span, lively prose and a moral sense – still have to contribute to public debate about war’s causes and consequences.

I have much pleasure in declaring Hell-Bent launched in this great city!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.