‘Water and gold: a book about the environmental impact of mining’, Honest History, 22 October 2019

Anne Beggs-Sunter reviews Sludge: Disaster on Victoria’s Goldfields, by Susan Lawrence and Peter Davies

Sludge – a very unpromising title for a book, not designed to exactly jump off the shelf. But this volume proves to be a very important and often gripping account of the history of water management in Victoria and of the battle between mining interests and the public good. The issue is still a burning one today with questions over the management of the Murray-Darling system.

Archaeologists Susan Lawrence and Peter Davies from La Trobe University have studied the way gold miners engineered water systems to facilitate their mining efforts in a dry climate. The authors’ arguments are soundly based in government reports, maps and local histories. There is an excellent index to give quick access to specific detail.

Archaeologists Susan Lawrence and Peter Davies from La Trobe University have studied the way gold miners engineered water systems to facilitate their mining efforts in a dry climate. The authors’ arguments are soundly based in government reports, maps and local histories. There is an excellent index to give quick access to specific detail.

Gold miners used the water to flush out gold from gravel and then sent the resultant mixture of water, sand and gravel, dubbed ‘sludge’, downstream, covering valuable river flats, and sometimes residential areas and roads, with a thick layer of mud. This set up a number of battles, between miners and farmers, between miners and local government officials, and between miners and colonial authorities concerned with supplying pure water to goldfields communities.

With the gold rush beginning in 1851, the question of ownership of water became a vexed one. According to English traditional law, the right to use water belonged to those who owned land on either side of the stream through which the water flowed. Landholders did not own the water, but had the right to use it and the responsibility not to pollute it or reduce its flow. Water was seen as a public asset, like air and soil.

From the 1850s, enterprising miners built dams and water races to supply their own mines and to sell water to other miners. Mining regulations in 1853 allowed miners to use water at running streams; enterprising miners freely interpreted this regulation as allowing them to divert water into races. Further legislation in the 1860s stipulated that miners had the right to use water for 15 years, but that the water itself was a public good, belonging ‘in public hands’. But the legislation did make water a tradable commodity and a marketplace for water was established. It was quickly accepted that entrepreneurs who diverted water from rivers could sell that water as recompense for the structures they put in place.

The authors estimate that ‘by the late 1860s the races and dams built by miners on the goldfields were able to carry more than 1.1 billion litres of water every day’. Miners also built massive waterwheels to power steam engines working underground deep lead and quartz mines.

Supply of pure water was one side of the story. The other side was the disposal of that water once it had been used in the mining process. The pure water had been mixed with soils and gravels and was released downstream as sludge, mine tailings that oozed over river valleys.

The issue of sludge was magnified in the late 19th century, when new methods of hydraulic sluicing and dredging were introduced into Victoria. These methods, which reworked old alluvial diggings along riverbeds, used prodigious amounts of water and caused enormous environmental damage to river banks and river valleys, particularly in north-east Victoria and on the Loddon River in Central Victoria.

By the 1870s, miners were using four times the amount of water used by the rest of the Victorian population. Around 1900 a dredge at Newstead on the Loddon was drawing 100 000 litres of fresh water an hour from the river to pump into the dredging channel it had constructed beside the river. This water, after it had been used to process river banks and gravels, was then flushed downstream as undrinkable water for man and beast, with the sludge flooding out to ruin valuable agricultural land. Mining effluent had contaminated three-quarters of Victoria’s rivers and streams.

These operations led to the development of anti-dredging groups of farmers, such as the Loddon Anti-Sludge Association and the Kiewa Valley Anti-Dredging Association. These lobby groups were important in drawing parliamentary attention to the damage caused by sludge and dredging, resulting at last in legislation in 1907 in a revised Mines Act, which began turning the tide in favour of farmers and government authorities charged with supplying drinking water to the population.

Gold mining rapidly decreased after 1900 and by the end of World War I the lobbying power of the mining industry had declined, along with gold’s contribution to the economy. The water races, waterwheels and dredges fell into disuse and the sludge problem was forgotten. Archaeologists like Lawrence and Davies now go out into the bush with old maps to find traces of these massive water projects of the 19th century.

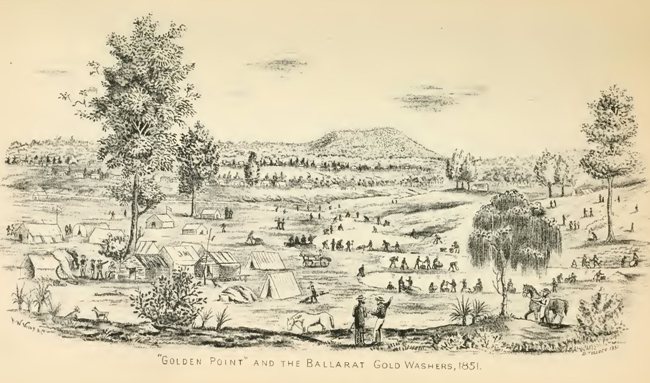

Golden Point and the Ballarat gold washers, 1851: Withers, The History of Ballarat (1887); Project Gutenberg

Golden Point and the Ballarat gold washers, 1851: Withers, The History of Ballarat (1887); Project Gutenberg

But the question of the environmental cost of mining remains a lively one in many parts of Australia, now particularly relating to mining in northern New South Wales and Queensland. The mining lobby is powerful in Canberra and environmental lobbies are in constant battle over efforts to protect the environment. The authors draw our attention to the continuing cost of rehabilitating old abandoned mines. Although state regulations now require mining companies to construct tailing dams to contain sludge and theoretically require that sites be rehabilitated after mining ceases, there are currently over 400 derelict mines in New South Wales. In cities like Ballarat and Bendigo there are still hundreds of deep shafts under the cities, the legacy of gold mining and the occasional cause of cave-ins and expensive remediation.

Sludge makes one see the landscape through new eyes. The romanticised story of the gold rush era in Australian history never mentioned sludge and rarely mentioned the tremendous environmental damage caused by mining. The book is a wake-up call about how we manage the public good of water in our future.

* Dr Anne Beggs-Sunter works in the Collaborative Research Centre in Australian History, Federation University, Ballarat. She has published widely on the history of Ballarat, her university and gold mining.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.