‘Armidale and the Great War’, Honest History, 21 September 2017

Frank Bongiorno* reviews Armidale and the Great War, by Ian M. Johnstone

One of the positive aspects of the centenary of World War I has been the stimulus it has provided to historical research and publication. There is, of course, a mass market for modern-day ripping yarns, a smaller general readership for more critical histories, and a continuing niche for academic studies.

There is another category of histories that can easily be overlooked in all this publishing activity, because they are the fruits of community rather than professional historians, are often self-published and mainly distributed locally, and they primarily address a family, local or regional audience. But, as in the case of this admirable book from Armidale historian Ian M. Johnstone, these histories can be the product of prodigious research, might carry some fine writing, and will unearth information, sources and stories that deserve a place in a wider historiography.

There is another category of histories that can easily be overlooked in all this publishing activity, because they are the fruits of community rather than professional historians, are often self-published and mainly distributed locally, and they primarily address a family, local or regional audience. But, as in the case of this admirable book from Armidale historian Ian M. Johnstone, these histories can be the product of prodigious research, might carry some fine writing, and will unearth information, sources and stories that deserve a place in a wider historiography.

It is, in fact, hard to imagine anyone other than an Armidale historian being able to produce a book such as this. Johnstone has behind him a vigorous local and regional historical culture, the Armidale and District Historical Society having been formed in 1959 and maintaining a lively publishing program over many decades, including its own fine journal. The society’s activities have long been the fruits of cooperation between local historians and history enthusiasts such as Johnstone, whose profession is the law, and academics at the Armidale Teachers’ College (later College of Advanced Education) and the University of New England. (The university controversially incorporated the college in 1989.)

The book itself is a community effort as well as being a product of the tireless efforts of an individual. The first half is devoted to a collection of biographies of about 90 local men and a dozen nurses who served in the war. These are of varying length and detail, many researched and written by Johnstone himself. In some cases, he has invited a descendant who has researched an Anzac ancestor to tell the story. This is a most effective method, avoiding duplication of effort, unearthing family memories and documents, and underlining what can only be achieved in a place where people know one another personally. Here, collective memory of the war’s legacy remains alive among older residents. It is easy to overlook this last point when you live in a much larger city, with its very different patterns of belonging, sociability and memory.

Jan Assmann, a scholar of ‘collective memory’, distinguishes between two types: ‘communicative’ and ‘cultural’. Communicative memory is everyday communication leading to ‘numerous collective self-images and memories’, and it is distinguished by ‘its limited temporal horizon’.[1] This variety of memory has a shelf-life of three or four generations – 80 to 100 years – which, of course, corresponds to the time since the Great War. ‘Cultural memory’, by way of contrast, is characterised by its ‘distance from the everyday’, as well as its role in constituting a social group’s identity.

So, while the modern Australian collective memory of World War I in general appears to match Assmann’s definition of ‘cultural memory’, I wonder whether, in considering many of the local and family historians responsible for assembling this collection, we still have a foot in the realm of communicative memory; that the people and events discussed here are still, to some extent, part of everyday communication? That said, children often learned little about the war from the horse’s mouth: ‘My father did not talk about his war service’, reflects the author of one entry, ‘and I now regret my lack of interest until recent years when he was sadly long departed. There was so much I could have learned from him’ (p. 45).

The stories of those who served are often fascinating, sometimes including quotations from diaries and letters still in family hands, in other cases quoting from a rich archive of local newspapers or records in the University of New England and Regional Archives. Armidale at the time of the war had a population only a little over 5000, although it was then the ‘capital’ of a wider region, New England, most famous for its wool production and pastoral families. Among these soldiers, some never to return, there were sons of these wealthy families, many of them former students of The Armidale School (TAS).

TAS figures prominently in this story, and not only through the boys it sent to war. The most famous name today among the Armidale soldiers is that of Leslie Morshead, best known for his command of Australian forces in North Africa in World War II, but also an accomplished officer in the earlier conflict and, from 1912 to 1914, a teacher at TAS. Morshead commanded the highly-regarded 33rd Battalion, formed in December 1915 and made up especially of men from the north-west of New South Wales.

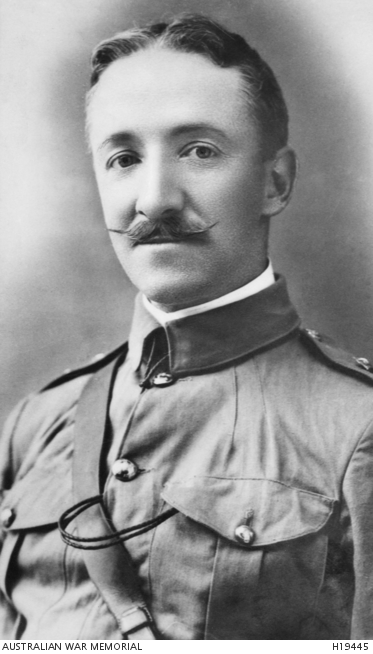

GF Braund (AWM H19445)

GF Braund (AWM H19445)

But the most famous Armidale name at the beginning of the war was George Frederick Braund, the local member of the state parliament, a Theosophist in his religious leanings, and Lieutenant-Colonel at Gallipoli. He also taught gymnastics at TAS. Braund was accidentally shot and killed in 1915 when he failed to hear a challenge by one of the sentries.

We seemingly find among the soldiers a cross-section of the community’s eligible men, Catholic and Protestant, labourer and clerk, the scions of pastoral dynasties and employees of the New South Wales Railways. There was a violinist. An Aboriginal man, Frederick Joseph Barber, enlisted – he said – because of ‘love of his country’ (p. 27) but on medical grounds he never served overseas. There were also the descendants of German migrant families. The family of Clifford Schmutter changed their name to Sheldon to avoid hostility from the Anglo-Celtic majority. Clifford was killed at Pozières, his body never found, but when his Australian-born father tried voting after the war he was prevented from doing so because of his German background.

The biographies also include 12 nurses, the most remarkable of whom was surely Hilda Hope McMaugh, ‘a fearless horse rider’ and the daughter of a stock and station agent. After service in Cairo, in 1919 she took up flying lessons and qualified as a pilot. After she returned to live at Uralla, the flying seems to have ended. She became matron of the Uralla Hospital, dying at the age of 96 in 1981.

Hilda Hope McMaugh (NAA/FrevFord)

Hilda Hope McMaugh (NAA/FrevFord)

This is not primarily a study of Armidale itself during the war, but we learn much about the stresses in the community. Soldiers did their best to reassure family. ‘I am safe as one can be in the firing line’ (p. 44), declared Bruce Bowning in a letter to his parents. The letter was subsequently published in the Armidale Express, but it is hard to imagine this well-meaning remark will have reassured his mother and father. One family published the following heart-rending plea in the Sydney Mail, along with the name and a photo of their son, more than a year after his disappearance: ‘Armidale – missing. He was last heard of at Lone Pine. Will anyone knowing anything of him communicate with his mother at Beardy Street, Armidale’ (p. 25).

At a memorial service in the gold mining town of Hillgrove for Marshall Morgan, killed at Gallipoli in May 1915, the clergyman – a Lieutenant-Colonel and Chaplain – used the occasion to appeal for more volunteers. What, from our vantage point, might seem like a mixture of appalling insensitivity and bad taste, made perfect sense in 1915, in a war regarded by such people as God’s cause. All the same, Armidale would vote against conscription in 1916 and 1917.

Where the soldier survived, the stories sometimes take up post-war life, so we learn of many apparently premature deaths, of the occasional returned man trying to make the best of poor land as a soldier settler, but also of seemingly successful lives lived quietly among family, friends and community. Some of these returned men must have carried the psychological scars of the war for the remainder of their days. A few certainly carried the physical marks. There was Bern Curtis, an amputee, who got around Armidale for the rest of his life on crutches, with ‘the Northern Daily Leader or the Sydney Morning Herald wedged in the lower fork’ (p. 63). It is quite an image.

The biographies are followed by a short reflection by Johnstone on the role of courage, humour and poetry in the war, which is in turn followed by 19 appendices. These include lists of soldiers, sailors and nurses on local memorials, a list of 124 soldiers from Armidale district killed in the war, men who served at Gallipoli, and a list of Armidale men’s graves in Belgium and France. Other appendices include essays of varying length, several republished from the Armidale and District Historical Society’s journal and proceedings, some by Johnstone, some by other local authors on various aspects of Armidale’s war.

These appendices occupy about half the book. Johnstone writes a biography of Arthur Cooper, TAS boy and son of the Anglican bishop. It is a classic, tragic ‘lost generation’ tale. Robin Hammond tells the story of the struggle over building war memorials in Armidale, showing that the decision to create a fountain was the result of an intervention by an outside body, the War Memorials Advisory Committee. Their decision – unpopular locally – was in favour of a fountain, in a town with a chronic shortage of water. Brilliant work. Hammond reveals another lighter, or at least ironic, moment: the memorial gates erected at the sports ground were accidentally demolished in 1962 by an army truck.

The most famous war memorial in Armidale district, however – and indeed, one of the most extraordinary built anywhere in Australia – is the private effort at Chevy Chase not far from the town. The brain-child of Alfred Perrott, and erected in memory of his son, killed in the war, and of two other men Perrott had persuaded to join up, it welcomes visitors with the word ‘NIRVANA’. Perrott had derived the idea from reading Edwin Arnold’s Light of Asia, a popular text that introduced many educated people in the Anglo-world to Buddhist ideas. The complex imagery of the memorial, with its circle and globe, obelisk, pillars, triangle and spire are explained on the memorial itself. It is a tribute to the British Empire, but also to a much-loved son and others who had lost their lives. Christine Thomas’s little essay explores the origin, construction and meaning of the monument. It was surely an amazing ecumenical moment: some of the tiles were apparently donated by the Catholic Bishop of Armidale.

Dangarsleigh memorial, with NIRVANA gate (Panoramio/James Vickers)

Dangarsleigh memorial, with NIRVANA gate (Panoramio/James Vickers)

There is a typically lively, witty and elegant essay by the late Lionel Gilbert, formerly of the Armidale Teachers’ College, on Min Blaxland, ‘The Diggers’ Queen’. A descendant of the famous explorer of the Blue Mountains, the unmarried Min corresponded with many local Diggers as a motherly figure, and threw herself into the war effort at home, especially the New England Soldiers’ Club, a local recreational facility, now the site of the Armidale Folk Museum. She also served in the local Voluntary Aid Detachment at the grand mansion Booloominbah, during the war a convalescent hospital, later the site of the University of New England. The story of Booloominbah’s wartime career as part of the Red Cross’s effort is told by William Oates, the UNE Archivist, and his colleague Ian Stephenson.

Other essays cover the early history of Anzac Day (John Farrell) and the war as seen in the Armidale Express compared with the Sydney Morning Herald (Ben Thorn), and there are two further essays by Johnstone on war poetry. A useful list of further reading provides a flavour of the range and extent of local and regional research on World War I, but also includes general studies of Australia’s war.

The book is presented in a large, A4 format and is generously illustrated; the images often contribute powerfully to the melancholic effect of so many stories of suffering and grief. Frank Brennan was probably not yet 20 when killed in France in February 1917. You can see him in a full-page illustration (p. 40), pipe in mouth, arms folded, braces holding up his trousers, a slouch-hat crowning the serious expression on his baby face.

Armidale and the Great War is a considerable feat of research, writing and curation by Johnstone, and an impressive cooperative effort by historians in and of Armidale. A fitting memorial in its own right, it is also a valuable record of a kind that can only emerge from a vigorous local history scene inhabited by people who care about both place and story. It reflects Johnstone’s own standing in the local history community in bringing together these authors, and his own humanity and sensitivity as an interpreter of the lives of others.

[1] Jan Assmann, ‘Collective Memory and Cultural Identity’, New German Critique, No. 65, Spring-Summer 1995, pp. 125-33.

* Frank Bongiorno FRHistS, FASSA, is Professor of History at the Australian National University and President of Honest History. For other Honest History posts by Frank Bongiorno, use our Search engine.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.