‘Across the sea to Ireland: Australians and the Easter Rising 1916 – highlights reel’, Honest History, 26 April 2016 updated

Update 31 May 2016: Geraldine Doogue on the ABC adds to our resources.

24 April 2016 was the 100th anniversary of the start of the Easter Rising (Éirí Amach na Cásca) in Dublin. The Rising lasted for five days, with more than 2000 casualties, including 485 deaths, half of them civilians. Sixteen leaders of the Rising were executed. The Rising was not widely supported in Ireland at the time but by 1922 there was an Irish Free State and by 1948 a Republic of Ireland.

Here we present highlights from a chapter by Stephanie James in a recent collection of conference papers (pdf made available by courtesy of Andrekos Varnava, co-editor). While 1916 was the year of Fromelles and Pozières, in Australia it was also the year of the first battle over conscription. The Easter Rising impacted on the attitudes of Irish-Australians both to events in France and to conscription. The history of a nation at war has many strands.

We add some material about direct Anzac involvement in the Rising, which seems to be one of the many occasions when Australian soldiers – or, on this occasion, perhaps just one of them – have helped the Empire of the day, from the Sudan in 1885, South Africa in 1899-1902, down to recent times. On this occasion, however, the Anzacs seem to have been on holiday.

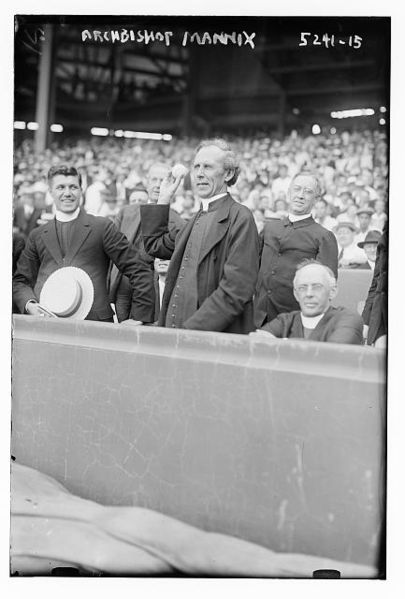

Archbishop Mannix of Melbourne throwing the first pitch at a New York Yankees game, Polo Grounds, New York City, c. 1920 (Wikimedia Commons/Bain News Service)

Archbishop Mannix of Melbourne throwing the first pitch at a New York Yankees game, Polo Grounds, New York City, c. 1920 (Wikimedia Commons/Bain News Service)

Loyalty becoming disloyalty? The War and Irish-Australians before and after Easter 1916 (Stephanie James)

Dr James provides a detailed account of how Irish-Australians responded to the war and how, in turn, other Australians responded to their Irish-Australian compatriots. Using primarily press sources, both mainstream and Catholic, James shows how Irish-Australian loyalty to the war was firm at first, because loyalty seemed to be a quid pro quo for Irish Home Rule, legislation for which had just passed the House of Commons. But things changed during the course of the war. James describes a continuum of loyalty to disloyalty and suggests that very many Irish-Australians were seen by non-Irish to have moved towards the disloyalty end during the war, with long-lasting effects on how Australians viewed each other.

Accusations of disloyalty or insufficient loyalty surfaced long before the Easter Rising or the

conscription plebiscites. Extraordinary wartime events ignited nineteenth-century agendas. Beneath the surface of the dominant Anglo culture emerged evidence of entrenched anti-Irish prejudice. Religious and cultural differences had largely constructed two societies in Australia. The dominant culture was largely distant from and broadly critical of Irish Catholics … In the crisis that was the Great War, hostility moved seamlessly towards unqualified verdicts of imperial disloyalty.

Antipathy towards Irish-Australians grew after the Rising, even though many Irish-Australians were shocked by events in Dublin.

When the 1916 Easter Rising unequivocally established Irish treachery, this established a species of “guilt by association” into which Irish-Australians, already seen as barely loyal, could now be definitely consigned. Horror, outrage and despair from prominent and ordinary, shocked Irish-Australians notwithstanding, the whole community stood condemned by the imperial disloyalty and betrayal of a few Irishmen [in Dublin].

While opposition to the first conscription referendum was primarily driven by trade union efforts and the scale of casualties on the Western Front, the leading role played by Archbishop Mannix against the second referendum fuelled attitudes towards Irish-Australians and

by late 1917, charges of Irish-Australian disloyalty had fully germinated, and Mannix led referendum opposition within an atmosphere of toxic, prejudiced hysteria. A larger referendum defeat ensured disloyalty charges were more universally believed, reinforcing accusations of inadequate Irish-Australian enlistment, or “shirking”.

Many efforts were made to show the loyalty of Irish-Australians, including releasing comparative enlistment figures and running features in Catholic newspapers on Irish-Australian Victoria Cross winners and Irish families contributing many soldiers to the cause. Some Irish-Australians opposed Mannix. On the other hand, Australian security services targeted Irish-Australians who were holding meetings supporting Sinn Fein and Home Rule and showing other signs of rebelliousness. The War Precautions Act was amended to make support for Sinn Fein and/or Irish independence evidence of disloyalty.

James sums up the factors that moved many Irish-Australians towards Empire disloyalty: the impact of Gallipoli; the Rising itself; the casualties on the Western Front; the battles over conscription in Australia, along with the introduction of conscription in Ireland; the War Precautions Act; the impact of tumultous Irish politics.

Behind all these factors, the impact of Archbishop Mannix, the consistency of his message, absolutely pro-Ireland and anti-Britain from 1916, and its greater visibility thanks to loyalist outrage, deserves recognition. But after Easter 1916 any Irish-Australian engagement with or interest in Ireland became synonymous with disloyalty. A sense of [Irish-Australian] betrayal over Home Rule [whose prospects seemed to be fading after the Rising] became more widespread.

In conclusion, though, James argues that the ‘bar’ of imperial loyalty came to be set too high. Being a member of the Irish ‘race’ was an inherent mark against qualifying as loyal. Acts like Irish-Australian singing of the rebel anthem ‘God Save Ireland‘ at Mannix’s meetings

reminded Irish-Australians of their identity, of history, of past British injustices to Ireland in that empire for which Irish and Irish-Australians were dying in the Great War. For the dominant [non-Irish] culture, it simultaneously confirmed disloyalty.

Anzac crackshots help the Empire against the revolting Irish

Raymond Keogh gives a graphic account of how his great-uncle Gerald was shot off his bicycle during the Rising. The bullet seems to have been fired by an Anzac soldier from the roof of Trinity College, Dublin.

Private MJ McHugh, 9th Battalion (Jeff Kildea/Australian War Memorial)

Private MJ McHugh, 9th Battalion (Jeff Kildea/Australian War Memorial)

Some Anzac soldiers just happened to be in Dublin on 24 April when the Rising erupted and were either hurriedly drafted into the British Army or took it upon themselves to lend a hand, with drastic consequences for Gerald Keogh and possibly others. Professor Jeff Kildea wrote a book in 2007 called Anzacs and Ireland, which included a chapter on the role of Anzacs in the Rising. A longer version of this chapter had appeared in the Journal of the Australian War Memorial in 2003 and there is a summary version in the Memorial’s Wartime magazine for 2006.

Kildea quotes one contemporary source that there were 30 Anzacs helping to defend Trinity College, which involved, among other thing, sniping at passing rebels, their accuracy earning high praise from witnesses. Other sources, however, suggest some of this number may have been South Africans and Canadians.

Kildea finds it hard to get beyond the number of about six Anzacs in the group at Trinity College, five of them New Zealanders, although he offers evidence of four Australians being involved in other actions against the rebels. The Australian on the roof of Trinity was most likely Private MJ McHugh of the 9th Battalion, a Gallipoli veteran who had been on leave after treatment in Britain for illness.

Kildea amassed a large amount of material, particularly in his 2003 piece, but admitted to being handicapped because relevant Australian War Memorial records had been culled in the 1950s. He concluded that we may never know how many Australians were in Dublin at Easter 1916 (and what they did) but felt it was reasonable to assume there were more than ‘the handful’, parts of whose stories have come down to us.

The Australian pamphleteer, DP Russell, asked later in 1916, ‘Did Australia’s sons in Dublin add lustre to the deeds of the heroes who fought and died in Gallipoli for the “Rights of Small Nations”?’ Russell’s rhetorical question seems not to have provoked an answer at this time. But did these men like what they (or some of them) were apparently pressed into doing? In his 2006 article Kildea quotes Private George Davis saying that he personally had no quarrel with the rebels but he did what he was ordered to do and made the best of a bad job. In his 2003 piece Kildea speculates that the Anzacs in Dublin probably opposed the Rising – as, indeed, did the majority of Irish men and women at the time – but, in any case, Kildea concluded, in the words of the 1914 Australian Imperial Force oath, ‘they would have seen it as their duty as loyal soldiers of the Empire to answer the call to arms and “to resist His Majesty’s enemies and cause His Majesty’s peace to be kept and maintained”‘.

Other material

The BBC has a summary of the events of the Rising. Eoin Hahessy has a summary of the effects on Australia which links to an exhibition at the State Library of Victoria. Andrew O’Hehir in Salon writes about the Rising as a failed venture with great consequences. Irish Central has lots of photographs. Barbara McCarthy in Al Jazeera. The Irish Times has a large bundle of material. A 2014 ABC RN Forum on conscription. Imperial War Museum footage. Paul Daley wrote in Guardian Australia and Compass interviewed Peter Stanley and Jeff Kildea. Matthew Ryan in The Conversation. ABC Big Ideas with Colm Toibin. ABC Radio National on the women of the Rising. (Some of these sources are dated around 2016’s March Easter, as Ireland traditionally commemorates the Rising at Easter rather than on the actual dates.)

Kilmainham jail yard, where 14 leaders of the Rising were executed, May 1916 (Irish Times)

Kilmainham jail yard, where 14 leaders of the Rising were executed, May 1916 (Irish Times)

What’s On

Honest History knows of events in Canberra to commemorate the Rising and will publicise others if they are brought to its attention: admin@honesthistory.net.au. The exhibition in Melbourne.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.