‘Republican past – and invigorating present and future’, Honest History, 23 March 2018

This Time: Australia’s Republican Past and Future by Benjamin T. Jones is reviewed by John Warhurst

Ben Jones represents the next generation of Australian republicans and – just as I was once inspired as a young South Australian by the republicans of the day (like Geoffrey Dutton and Max Harris), who had it much harder – I am confident that Jones will be similarly inspirational.

In person, Jones exudes enthusiasm, creativity and optimism for the republican cause. This is a much-needed tonic for those 1990s and 2000s leaders who may have become jaded, pessimistic and/or cautious because of their experiences of failure. Jones, by contrast, is up-beat, bold and not afraid to be critical, where necessary, of those reformers who have gone before him.

In person, Jones exudes enthusiasm, creativity and optimism for the republican cause. This is a much-needed tonic for those 1990s and 2000s leaders who may have become jaded, pessimistic and/or cautious because of their experiences of failure. Jones, by contrast, is up-beat, bold and not afraid to be critical, where necessary, of those reformers who have gone before him.

These are the virtues to be found in Jones’ latest book, This Time: Australia’s Republican Past and Future. While the book is relatively short, it is comprehensive, providing a critical tour of the distant and recent republican past, as well as an invigorating look at the present and the future, including making its own suggestions for the way forward. Jones is thoughtful and not afraid to be inventive.

Jones shares some characteristics with Peter FitzSimons, the current chair of the main lobby group, the Australian Republic Movement (until recently ‘Australian Republican Movement’), who has written a Foreword. Jones would appreciate the tone FitzSimons sets, echoing John O’Grady, in describing Australians as ‘a weird mob’, whose national characteristics – egalitarianism and independence – seem so much at odds with having a Head of State who is not just a hereditary monarch, but British to boot.

Australia’s situation, in Jones’ terms, is a riddle. He quotes his mentor, the late historian John Hirst, that ‘Australia was born in chains and is not yet fully free’. Jones thinks Australia is like Hamlet, whose ‘tragic flaw was hesitation’: ‘so Australia has hobbled into the twenty-first century still unsure of its place in the world’.

The book’s introduction sets the unapologetic, passionate tone: ‘Australia too has given in to fear. Lacking leadership, national pride and a strong sense of self, it has clung to imperial relics and symbols long after they lost their meaning and relevance.’

The introduction also explains the book’s title. Australia has considered the republican question before, in the 1850s, the 1890s and the 1990s. Each time, we have hesitated – as we are doing now: ‘Yes, but not yet, we say still. But if not now, when?’ Jones believes now is the time. His introduction also unveils a style which is humorous, sharp and eminently readable.

The book itself is divided into two parts of four chapters each. The first part is a compact history of republicanism from colonial days to the 1999 republic referendum. Chapter 2 ranges from John Dunmore Lang, ‘the father of Australian republicanism’, whom Jones compares to FitzSimons – ‘physically imposing, a witty and humorous speechmaker, history buff, popular author, columnist and passionate republican’ – to other early republicans like Daniel Deniehy, who derided ‘the bunyip aristocracy’.

Chapter 3 focusses mainly on Federation, a moment often falsely equated with independence – ‘the greatest myth in Australian history’ – when, in reality, the precise moment of ‘independence’ remains a puzzle, with various dates during the 20th century (Gallipoli 1915, Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942, Australian Citizenship Act 1948, Australia Act 1986) staking a partial claim. The chapter also discusses the strange evolution of our National Anthem, Advance Australia Fair – in, then half-out, then in again between 1974 and 1984 – which was meant to symbolise a new national identity, and the 1986 Act, which ‘did not tackle the hard subject of how we might become a republic’.

That forward-looking moment came in 1999 (Chapter 4) when Australian republicans, according to Jones, learnt a lesson on ‘How to lose a referendum’. That was the year in which a minimalist republic was rejected, for reasons which remain much disputed. Two things which cannot be disputed are that the process, including a Constitutional Convention, was overseen by a monarchist prime minister (John Howard), who swore – and still swears – his objectivity, and that the so-called minimalist republic was largely defeated by other direct election ‘real’ republicans who, Jones reminds us, were so confident that a republic was inevitable that they took up Howard’s offer to join the ‘No’ case, in order to defeat what they regarded as a ‘pretend’ republic.

Jones is unforgiving of those direct election republicans, like Ted Mack, Clem Jones and Phil Cleary, who were fooled by Howard and the monarchists. The past is done for now but, in a warning to all republicans, Jones is in no doubt that, should a second referendum fail, ‘whatever the model under consideration, the shame will belong entirely and eternally with every faux republican who votes No’. This warning underpins the second part of the book.

In Part Two, Jones doesn’t mince words about muddled monarchists (Chapter 6), but does admit that monarchist groups have been ‘pretty shrewd marketeers’ and ‘effective in getting their well-scripted message across’. Demolishing such arguments is essential to engaging with the middle ground who, rather than the rusted-on opponents, eventually decide any referendum or election result.

Jones’ analysis covers six of the most common status quo arguments, the ones which always serve to muddy the water. They were all used in 1999 and will be again. Of these, the most important is the myth that the stability and achievements of Australian democracy have been built somehow on the monarchy. Once again this reflects our amazing lack of national self-confidence in our own Australian values and culture. Let’s celebrate them rather than falling back on hackneyed negative arguments for which there is no evidence.

Jones, like me, wants an Australia in which Australian symbols are wholeheartedly and unashamedly Australian. These non-constitutional symbols, like coins, flags and anthems, should be advanced immediately, where they do not already exist.

Finally, in Chapter 8, Jones offers his own model recipe for the way forward: the Jones-(Paul) Pickering model, which is a hybrid of the minimalist and the reformist models for choosing our Head of State. I’ve already advanced this model myself to a group of sympathetic older voters, and it certainly begins discussion – as it is meant to. In brief, it works like this: eight nominees/candidates for Australian Head of State, one from each Australian State and Territory Parliament chosen by a 2/3rds majority, are voted on in a popular national vote.

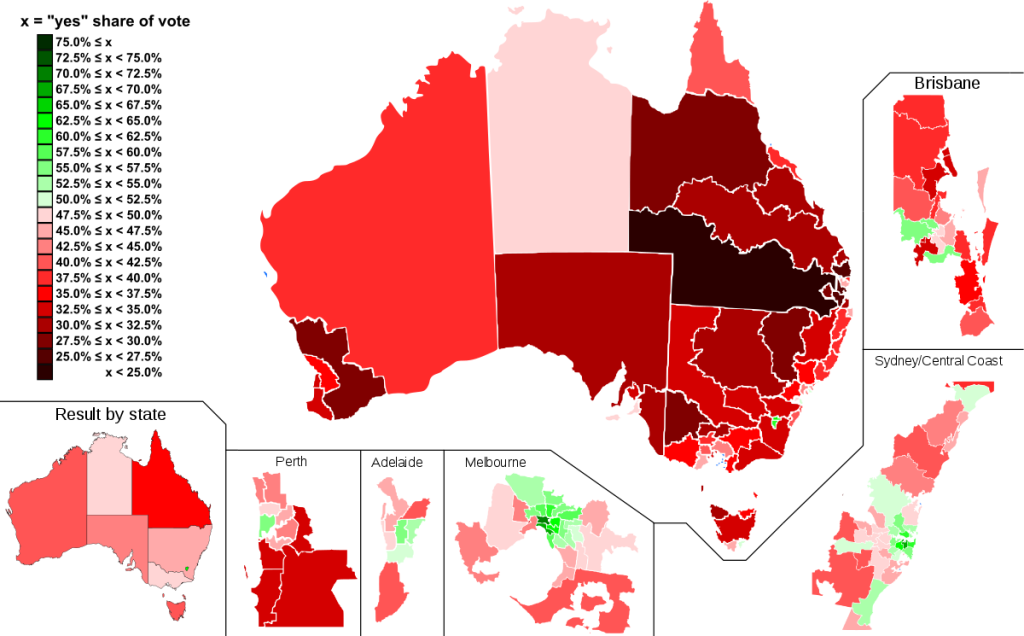

Referendum vote 1999 (Wikipedia)

Referendum vote 1999 (Wikipedia)

I agree with Jones’ conclusion that there will be no republic without passion, based on the love of republicans for this country and a determination to stand up for egalitarianism, democracy and meritocracy (rather than heredity) within the Australian community. But his conclusion – ‘It is not enough to support a republic in theory but excuse yourself from the hard work of debate and agitation’ – needs to be expanded.

Debate and agitation are not always easily come by in Australian public life. As a life member and former head of that often maligned lobby group, the Australian Republic(an) Movement, I would add to debate and agitation a third necessity, organisation. Whatever form that organisation takes and under whatever type of leadership, whether it be political or community leaders, eventual success will take organisation and hard work, not to mention resilience and courage. For these reasons, neither the timing nor the precise form of an Australian republic are yet possible to predict. Let’s just hope it is sooner rather than later.

* John Warhurst was chair of the Australian Republican Movement, 2002-2005. He is also an Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the Australian National University.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.