‘The Web of Empire (1902): highlights reel of a royal visit to Brisbane’, Honest History, 2 May 2017

Members of the Royal Family have visited Australia regularly since Prince Alfred was here in 1867. (He was shot by an Irishman but survived; the Irishman didn’t.) Mark McKenna’s chapter in The Honest History Book has more on royal visits to Australia and the mutual reinforcement between the Crown and the Anzac legend.

While this parade of royalty is reasonably familiar to many Australians we know rather less about the hangers-on, the flunkeys and Fauntleroys and Lady Philomenas who danced attendance on the distinguished visitors. It takes a lot of people to move a Duke or Duchess, a Prince or Princess, from one side of the world to the other and transport for the earlier trips was slow. Some of the hangers-on had time to write up their impressions and some of these impressions, in turn, were published.

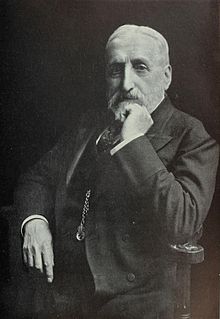

Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace (Wikipedia)

Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace (Wikipedia)

One example comes from Donald Mackenzie Wallace, born in 1841 in a lowland Scottish village with the unprepossessing name of Boghead. Wallace was highly educated, was a bit of a Russia hand, worked at one point for the ill-fated Czar Nicholas, spent some time in India, once carried an important document sewn into the lining of his coat, wrote some books and for The Times, was knighted (twice) and died, still a bachelor, near the sea in Hampshire in 1919.

Wallace’s final book, The Web of Empire: A Diary of the Imperial Tour of their Royal Highnesses the Duke & Duchess of Cornwall & York in 1901, was just what the sub-title says: a senior flunkey’s (he was private secretary to the Duke) story of the tour of the two royals (later King George V and Queen Mary) to Gibraltar, Malta, Aden, Ceylon, Australia, New Zealand, Straits Settlements (Malaya), Natal and Cape Colony (South Africa), and Canada. Hell of a trip, from March to October.

During the tour the Duke opened the first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. (The Duke and Duchess had been subbed in after the death of Queen Victoria, which left the original intended tourist as King Edward VII and needed at home.) The highlights below (from pages 167 to 171 of the original volume), however, concentrate on Sir Donald’s impressions of some of the Indigenous Australians the tourists saw. The impressions are in many respects offensive to a modern sensibility but they are very likely representative of those of upper-class Britons (even Scotsmen) of 1901. Carry on, Sir Donald.

_______________________

The royal party arrived in Brisbane on 20 May, pretending to arrive by sea but actually coming by train and chugging into a small suburban station, from where they were smuggled away for a rest at Government House before emerging again, to be placed on a boat (the Lucinda) to steam up the Brisbane River, as if they had come from the larger royal vessel, the Ophir, in Moreton Bay. (The plot was actually more complicated than this but that amount of detail will suffice.)

As soon as she [the Lucinda] comes near, the pent-up feelings of the spectators find vent in prolonged cheering; and in compliment to the Duke’s known interest in homing pigeons, five hundred of these beautiful birds are suddenly released, and fly away with the glad tidings to their respective homes.

The Mayor speaks, with allusions to the Duke’s previous visit to Brisbane 20 years earlier, when His Royal Highness was not shot by an Irishman (as his father was in 1867) but, as a 15-year-old midshipman on a Royal Navy vessel, may have had other dangers to confront.

[T]he Duke makes a reply in which he explains how gratifying it is for him to observe that the progress which Queensland has made has enhanced rather than diminished that characteristic loyalty of its people to the Throne and Empire, to which the gallantry of her sons [in the Boer War in South Africa] has of late rendered such inestimable service; several thousand neatly dressed school-children sing the National Anthem, the “British Flag of Freedom,” and other patriotic songs; the vast concourse of spectators cheer again and again.

The decorations put up for the visit are not as ostentatious as in Melbourne but are appropriately tropical and lush.

Of the fauna [sic] also we notice one genus which was conspicuous by its absence in Melbourne — the aboriginal population. All over Victoria the natives are few and rarely seen. They are an insignificant element of which the Colony has no reason to be particularly proud, and consequently they remain in the background. In Queensland they are more numerous, and on this occasion they are used for decorative purposes, having a triumphal arch all to themselves.

Sir Donald describes the arch (pictured and further described here) in a little detail then goes on to the

sixty stalwart black figures of gigantic stature, in scant costume and war-paint, the one at the summit [of the arch] seeming to be considerably over six feet high. My first impression is that the artist, while displaying wonderful accuracy in the modelling of the figures, has been guilty of a little exaggeration in the matter of size, but a remark to that effect is received with derision by my companions in the carriage. “Do you not see that the piccaninnies are moving, and the gins (women) also?” Quite true! The gins and piccaninnies are alive! And so are the men, though they stand motionless as bronze statues, in striking contrast to the excited, gesticulating, cheering crowd beneath them. Not only at this point, but all along the line from the landing-jetty to the gates of Government House, the enthusiasm of the white spectators never flags for a moment.

Navy race on the Brisbane River c. 1900-10 (Wikimedia Commons/John Oxley Library)

Navy race on the Brisbane River c. 1900-10 (Wikimedia Commons/John Oxley Library)

Later, the visitor is able to get more closely acquainted but confesses mixed feelings.

Since I saw them on the triumphal arch the blacks have entirely lost their martial, picturesque appearance, for they are now dressed in shabby civilised costume, and are chattering like children in broken English. A few of them, I must add, speak our language remarkably well, and give evidence of a higher kind of intelligence than is commonly attributed to them.

One of these gentlemen happens to share the Wallace surname.

Without further ceremony I claim acquaintance with my namesake, and try to extract from him and his pal some information about the present position and future prospects of the race. In accordance with previous experience in various parts of the world, I find that the noble savage has, as a rule, little sympathy with the disinterested curiosity of scientific inquirers. Quite indifferent to the benevolent interest which I am ready to take in his unfortunate race, my worthy namesake prefers to go and chat with a friend about matters of a practical rather than a scientific kind.

He seeks out another recent acquaintance, who has an official position.

I have to apply, therefore, to Mr. Meston [the Protector of Aboriginals in Southern Queensland], who knows the Australian Blacks well, speaks several of their dialects fluently, and has a sentimental affection for the race generally. He assures me that they have been grossly calumniated by their white brethren, and that they possess many good qualities commonly denied to them. Unfortunately, they have many of the defects of children, and they show themselves incapable of prospering in the conditions of what we call civilisation, even in those latter days when the Government is ready and anxious to protect and help them.

Even by the admission of this friend of theirs, who has long worked for them and amongst them, they are doomed, and the extinction of the race is merely a question of time. All that can be done by the philanthropist is to make the process of extinction as slow and as painless as possible. Since they took to wearing clothes they have developed a very marked tendency to consumption and cognate pulmonary complaints; and the fecundity of the race, never perhaps very great, is rapidly diminishing. The birth-rate is extremely low; many of the children die early, and among the few who survive a very large proportion are half-castes, the existence of which, I am assured, does not lead to those domestic dissensions which would inevitably be the result among races of a higher type.

And a sporty, shattering finish.

In their own special arts their hand seems to be losing its cunning. One of them kindly shows me how to throw a boomerang, but he does not impress me with his skill, and my doubts as to the accuracy of his aim are confirmed when, after one or two bad shots, he unintentionally breaks a pane of glass in the facade of the Public Library!

Having written up his notes of the day, Sir Donald went with the Duke and Duchess to dinner with Sir Samuel Griffith and other notables.

The Duke (carpeted) at Government House (Everywherehistory/John Oxley Library)

The Duke (carpeted) at Government House (Everywherehistory/John Oxley Library)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.