‘Who speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?’ (review of Babkenian and Stanley), Honest History, 19 May 2016

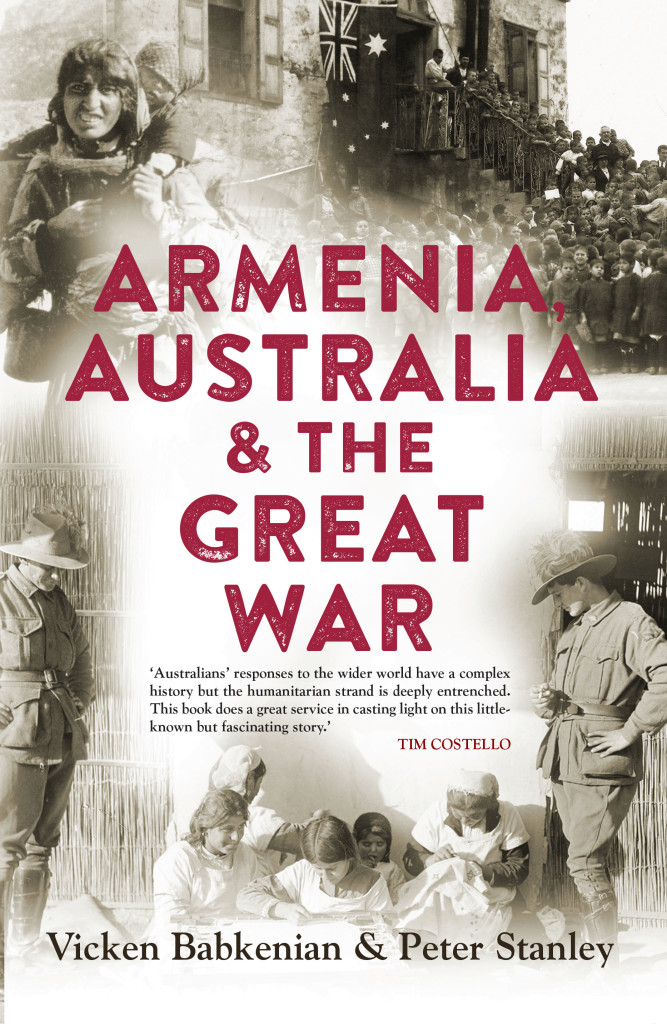

Gareth Knapman reviews Armenia, Australia and the Great War by Vicken Babkenian and Peter Stanley

‘Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?’ These were words that Adolf Hitler purportedly uttered, before he began the genocidal campaign of extermination of the Jewish people. The answer is that the Armenians are remembered as the people who, between April 1915 and 1922, suffered the first genocide of the 20th century. In recent years, the memory industry has shone a light on the Armenian genocide and the role it played in demonstrating the need for International Law to recognise crimes against humanity.

In their skilfully constructed work, Armenia, Australia and the Great War, Vicken Babkenian and Peter Stanley have approached the Armenian story from the perspective of Australia’s involvement in the Great War. The Armenian genocide began on 24 April 1915; therefore, the Gallipoli landings cannot be separated from the plight of the Armenians. Many people have concluded that the genocide was a consequence of the Gallipoli landings but Babkenian and Stanley rightly avoid making such a simplistic connection.

In their skilfully constructed work, Armenia, Australia and the Great War, Vicken Babkenian and Peter Stanley have approached the Armenian story from the perspective of Australia’s involvement in the Great War. The Armenian genocide began on 24 April 1915; therefore, the Gallipoli landings cannot be separated from the plight of the Armenians. Many people have concluded that the genocide was a consequence of the Gallipoli landings but Babkenian and Stanley rightly avoid making such a simplistic connection.

The plight of the Armenians was a continual theme for Australians during the Great War, with fundraising campaigns beginning as early as 1914 and continuing into the 1920s. Babkenian and Stanley weave a narrative through a series of connected stories. They begin with the first Armenians living on the 19th century Victorian goldfields, Armenians who served with the Australian military during the Great War, Australian fundraising charities to relieve the plight of the Armenians, and, finally, government policy within an imperial framework. Through these distinct but connected stories the authors have produced a cohesive account of Australian responses to the genocide.

Babkenian and Stanley also demonstrate a problem in writing about Australian foreign policy during the early 20 century: it is hard to decide where Australian policy begins and where British imperial policy ends. Much of the book charts the British Empire’s response to the Armenian genocide. Australia does not have an independent voice at this time and so Babkenian and Stanley cannot take the traditional approach of military and diplomatic history in exploring Australian government policy and actions. Perversely, this lack of an independent voice is also the reason why Australians were involved in the Armenian plight in the first place. The Armenians were a moral and strategic problem for the British Empire and so Australia’s involvement was always within that context. If Australia had run an independent foreign policy voice at that time, she may never have been involved in the British Empire’s conflict with the Ottoman Empire. This is the essential point raised by Henry Reynolds’ new work Unnecessary Wars.

Australian involvement in the Armenian plight was therefore limited to the sphere of ‘civil society’ (primarily fundraising for relief charities) and limited political lobbying within the imperial network. These Australian initiatives are coupled in the book with the actual experience Australian solders faced, when encountering destitute or mutilated Armenians, while the Australians fighting the Ottoman Army in Palestine as part of the British Empire’s combined military force.

Babkenian and Stanley’s approach of writing the Australian story within the imperial context is at times disjointed and strained, due to the haphazard response that Australians had towards the genocide. This difficulty could have been mitigated, however, if the authors had chosen to write a scholarly rather than a popular account. A scholarly approach would have allowed greater engagement with the problems around interpreting Australian responses. The popular historical focus also limits the narrative’s capacity to address the question of what constitutes a genocide. Wisely, however, the authors have only used the word ‘genocide’ in the narrative after it was coined by Raphael Lemkin in the 1930s, partly to refer to the plight of the Armenians.

Babkenian and Stanley have drawn extensively on newspaper reports and missionary accounts to tell how the genocide happened and how the Australian and wider British public responded to the slaughter. The authors use the descriptive terms from the time, such as ‘atrocity’, ‘outrages’, ‘depravations’ and ‘starvation’ but also ‘holocaust’ – the last word had been used to describe the earlier mass killings of Armenians in the 1890s.

Armenian victims, c. 1915 (Wikimedia Commons/Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story*)

Armenian victims, c. 1915 (Wikimedia Commons/Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story*)

Yet the use of these terms also points to a problem people faced in the Great War and at the beginning of the 20th century. The terms are euphemisms for rape and mass murder but they were commonly used to describe the actions of enemies during the Great War. While reading Armenia, Australia and the Great War, I continually wondered whether the lack of appropriate terminology – and even a kind of flippancy in the use of terminology – created a problem for Australians in understanding the scale and the deliberate and horrific nature of the mass murder of the Armenians.

The lack of appropriate terminology from the time may also go some way to explaining how modern day deniers of an Armenian genocide continue to wilfully ignore the overwhelming evidence of an Ottoman government orchestrated campaign to murder hundreds of thousands of their own subjects. This book is an excellent account of the genocide of the Armenians and of Australia’s role in an often forgotten aspect of the Great War.

* Original caption: ‘THOSE WHO FELL BY THE WAYSIDE. Scenes like this were common all over the Armenian provinces, in the spring and summer months of 1915. Death in its several forms – massacre, starvation, exhaustion – destroyed the larger part of the refugees. The Turkish policy was that of extermination under the guise of deportation.’ Henry Morgenthau was American Ambassador in Constantinople 1913-16. His book Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story was published in 1918.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.