‘The Wobblies at War’ (review of Cain), Honest History, 11 July 2017

Rowan Day* reviews Frank Cain’s The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia

This is a republication of Frank Cain’s 1993 book of the same title. Close to a century since the rise and (pushed) fall of the Australian incarnation of the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies), it is an apt time for the book’s reprint. In Australia, the Wobbly movement burned as fiercely as anywhere. This book is a very readable overview of an important movement in Australian history and I would recommend it to anyone with an interest in the IWW or early 20th century Australia.

This is a republication of Frank Cain’s 1993 book of the same title. Close to a century since the rise and (pushed) fall of the Australian incarnation of the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies), it is an apt time for the book’s reprint. In Australia, the Wobbly movement burned as fiercely as anywhere. This book is a very readable overview of an important movement in Australian history and I would recommend it to anyone with an interest in the IWW or early 20th century Australia.

While the timing of the re-release is fitting, it is perhaps a missed opportunity. Since the book’s first publication almost a quarter of a century ago, there has been some important scholarship on the IWW, both in Australia and internationally. Knowledge of the Australian IWW’s deep rural roots, its maritime activities, its transnational links, its social basis have all been added to in that time, but the most recent secondary source cited in the book is dated 1988.

The book could have investigated some questions that were not thoroughly explored in the 1993 edition. What gave rise to such support for the IWW in Australia? What kind of lives did Wobblies live? What did they do for work? For a movement that so thoroughly rejected reliance on ‘leaders’, could we have learned more about the lives of some of the Wobblies other than the prominent (largely foreign) leaders like Tom Barker, JB King and Tom Glynn? These men were important to the story, but were they really typical of the Australian Wobbly? As a movement that had its origins in the United States, did the Australian incarnation of the IWW show any notable differences?

Something Cain does very effectively, however, is document clearly the legislative, judicial and intelligence onslaught against the IWW during the war that killed it off prematurely, in an organisational sense at least. Billy Hughes argued the IWW needed to be attacked ‘with the ferocity of a Bengal tiger’, and this was not an empty threat. Australia’s infant military intelligence, short of German spies to track, turned their full attention to the IWW.

That we know so much about the Wobblies is partly because the state monitored them so effectively, including intercepting correspondence. This activity is also effectively explored in another of Cain’s works, The Origins of Political Surveillance in Australia (1983), which should be required reading at this time of mass electronic surveillance that would make the Stasi blush. Perhaps you could re-issue that book too, Frank!

The war provided the climate for this to happen. But despite the book’s sub-title, the war is not the central focus of the book, though it does receive attention. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as the Wobblies’ attitude to the war and the conscription debate particularly is, erroneously, what they are remembered for in Australia. Yes, the Australia IWW opposed the war, with scathing criticisms of its architects. But opposition to the war was never its raison d’être. For the Wobblies, what mattered above all was the economic struggle, the wage slaves versus the boss class. The fact has largely been forgotten, but the IWW in America was split on whether to oppose US involvement in World War I, with many American Wobblies feeling such opposition would distract from their core message.

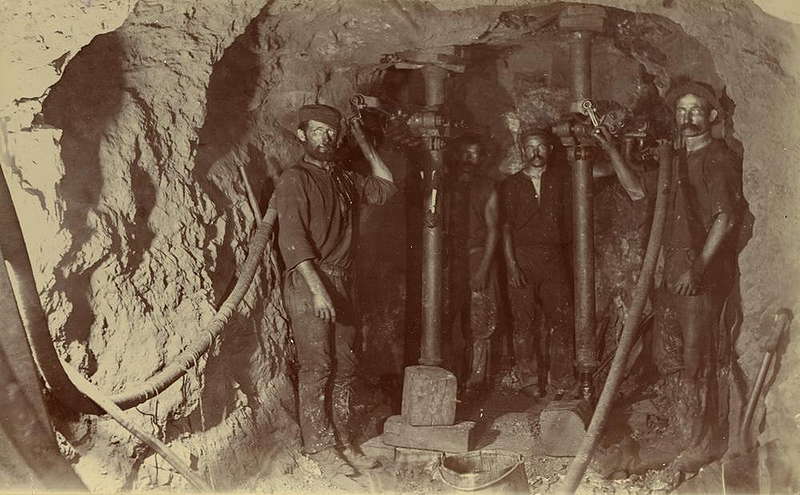

Mount Morgan miners, 1903 (Bonzle/Queensland/QldPics)

Mount Morgan miners, 1903 (Bonzle/Queensland/QldPics)

The IWW focussed on the economic struggle for a reason, a reason summed up in their 1917 assessment of Mount Morgan, Queensland, where a number of Wobblies worked in the gold mines:

Fat only makes about three quarters of a million a year out of the hides and muscle and sinew of the wage workers of that town. Every quid is a tragedy, a tragedy of broken bodies, and crushed limbs, of miners’ complaint, and of young and vigorous manhood murdered by the plundering profit-ghouls, at the portals of manhood. Mount Morgan is hell. It is hell so that Park Lane may be heaven.

The Wobbly focus on economic struggle did not spring from theory or abstraction. It sprang from lived experience. That experience was toiling down a mine, toiling over sheep, toiling with railway sleepers. Such toil did not lead to any great amount of thought about race or gender, as later comfortable-class thinkers have liked to pretend. Rather, such toil led to one question above all: why should Mount Morgan be hell?

* Rowan Day is the historian at OCP Architects, Surry Hills, Sydney. He is the author of Murder in Tottenham: Australia’s First Political Assassination.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.