‘Sums and parts in a new collection’, Honest History e-Newsletter, No. 6, October 2013

Australian History Now (edited by Anna Clark and Paul Ashton) NewSouth, Sydney, 2013

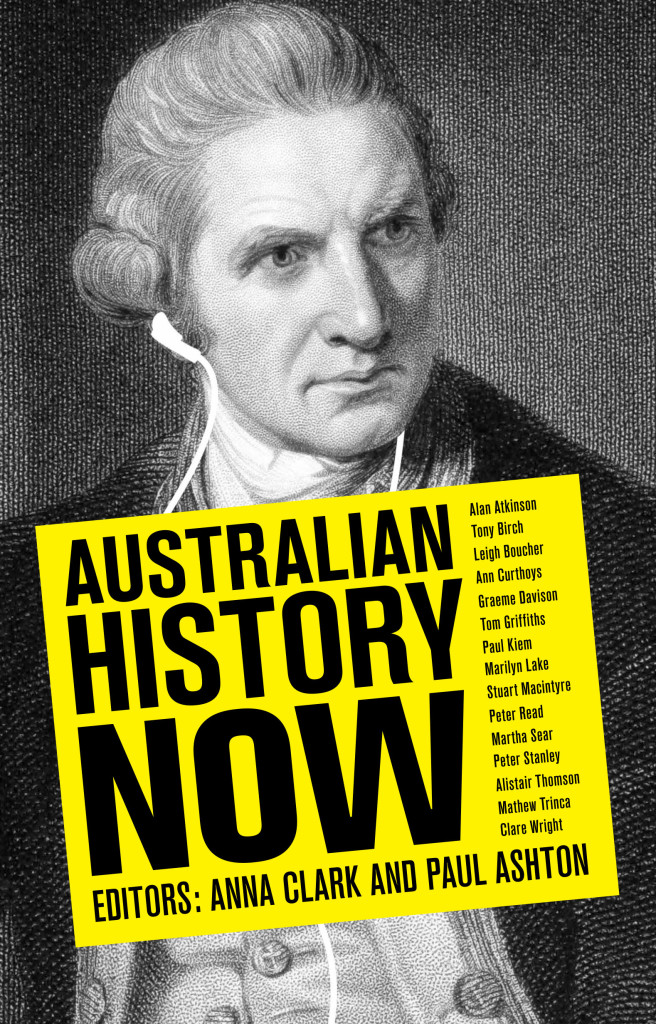

What does the sum of a book’s parts add up to? Increasingly today publishers of monographs and multi-authored titles behave as if they are producing an issue of a journal. Each article – and each chapter – is registered and allocated its own key words to enable individual packaging and sale. Although Australian History Now is available for purchase in paperback, Kindle and Pdf versions, it seems in fact it is not available as individual separate parts. The structure of the book, however, has ensured that if NewSouth Publishing changed its mind, it could sell stand-alone chapters without fear of reader confusion, such is the nature of editors Paul Ashton and Anna Clark’s anthology. Each chapter can be read and appreciated alone. There are no strong clear shared themes. I’m not completely sure whether this is a good thing or a bad thing, although it does reflect on the unifying power of the book’s Introduction.

Let’s then, first, consider the 17 chapters of the book and, secondly, the Introduction and its rationale for the book as a unified text.

Chapter authors – who they are, who they aren’t

In their Introduction, the editors explain that the authors of their 17 short chapters are ‘experts in their field’. A quick scan of their biographies tells us what a longer title or the missing subtitle might otherwise have told. Essentially, the book is about (i) the practice of academic scholarly Australian history and (ii) how history has been represented (e.g. in schools, museums, the media and communities). The book is written primarily by academic scholars. Ten of the authors are or were professors and most of the remainder are from within the academy. The few who are based elsewhere, like secondary school history teacher Paul Kiem or museum curators Martha Sear and Mat Trinca, have history doctorates.

So the question the editors raise in passing (p. 19) ‘Can anyone be a historian now?’ is just a tease. (The strongly-implied answer is, of course they can, but they are definitely not to be heard in this book.) Equally tantalising is the treatment of genealogy, mentioned three times in passing in 300 pages. So is Paul Ashton’s observation that ‘the internet rapidly shrank the world of history. Ordinary people were able to access sources that had largely been restricted to academics on sabbatical or the well-to-do.’

Other non-academics include those who do oral history, whose ranks, Alistair Thomson tells us in chapter 4, include local historians, adult educators and schoolteachers, as well as historians in museums, libraries and the media and thus easily outnumber academic historians. Expanding on the list, in her impressive chapter 12 (‘History in communities’) Martha Sear describes history-making in Hay, NSW, noting its local museum, educational, heritage and economic and social role, value and impact. She reminds us that there are about 1000 groups affiliated with the Federation of Australian Historical Societies and about 3000 local and community museums. All undeniably are part of Australian history now.

The only author to comment directly on the professional-amateur dimension to this academy-community divide is Peter Stanley. He briefly discusses [military] ‘storians’, i.e. journalists ‘whose characteristically long books reach large popular readerships’ (p. 101). (Given its implied judgment, Peter’s label sits uncomfortably with Clare Wright’s comment (p. 230) about historians and media practitioners that ‘We are all, in essence, story-tellers’.) Of the three storians Peter instances – Paul Daley, Les Carlyon and Peter FitzSimons – it is the latter two he sees as exponents of ‘the turgid nationalist epic’ (p. 102).

The abrupt and unelaborated juxtaposition of these descriptors with mention that Carlyon and FitzSimons were appointed to the Australian War Memorial Council flags the need for a major study of Council appointments – appointments by both Labor and Coalition ministers. Perhaps when everyone has finally tired of mentioning the history wars – which practically all authors feel the need to do, despite there being a separate and quite personal chapter on it by Anna Clark in chapter 9, ‘The history wars’ – we could have more actual case studies of the Council and its role. There have been plenty of battles and not only inside the Memorial and the National Museum.

In summary, it is academic historians who the editors invited to survey the changes of the past thirty to forty years within their particular sub disciplines. Apart from the editors themselves, chapter authors comprise Alan Atkinson, Tony Birch, Leigh Boucher, Ann Curthoys, Graeme Davison, Tom Griffiths, Paul Kiem, Marilyn Lake, Stuart Macintyre, Peter Read, Martha Sear, Peter Stanley, Mathew Trinca and Clare Wright. Nothing, then, from independent scholars and writers; nothing from the likes of Rachel Buchanan, Pat Clarke, Gideon Haigh, Chris Masters or Ross McMullin.

The results

Opening sentences matter. Here are the chapter authors’. See if you can match the names above to the list below, which start and end with my favourites.

He came to the door resplendent in a silk dressing gown, eyes sparkling.

I began life as a university undergraduate in 1988 at the University of Melbourne, at the age of 30, and chose English and history as my majors.

In primary school in the mid-1960s, my favourite subject was Social Studies.

I can’t usefully start this chapter by asking ‘Who writes Aboriginal history?’ because the written word forms but a small part of the historical endeavour.

Picture this imagined, but typical, day of history-making in and around the town of Hay in the New South Wales Riverina a decade ago.

As I undertook my training as a historian of colonial Australia in the 2000s, I felt that my fellow academics must have been constantly dizzy.

The aim of ego histoire, as articulated by the French historian and theorist of the relationship between history and memory, Pierre Nora, is to use reflection on one’s personal experience of the past to enhance our practice as historians, both substantively and methodologically.

The forest is beautiful and mysterious.

The National Museum of Australia’s public opening was a rare hurrah moment in what otherwise was the nation’s downbeat celebratory year of 2001.

For as long as I can remember, I have been walking the streets of Melbourne.

When Duncan Waterson, then Professor of Modern History at Macquarie University – who was later to become my PhD supervisor – turned 50 in 1985, his colleagues held a barbecue for him on Macquarie’s rolling green campus.

The point of this chapter is to sketch some of the main issues of research and practice in history in the universities since the 1960s.

Radical nationalism can strike in unexpected places.

In November 2000 the radical eccentric, Bob Gould, hosted a debate between Henry Reynolds and Keith Windschuttle in his rambling Sydney bookshop.

In the autumn of 1980, I started work in the History and Publications Branch of the Australian War Memorial.

A few years ago a young historian wrote to me to report on her current research on the cultural, commercial and political relations between Sydney and Shanghai in the 1920s.

The producer asks me to lie on the bed.

In their Introduction, the editors describe their authors as ‘eminent writers of history’. Judged by their chapters, mostly I’d agree, although the weakest read too much like annotated bibliographies with connecting career biography and historiographical text. And/or they are written in a style forever ‘interrogating’, being ‘complicit’ in, ‘locating’ or ‘contesting’ this or that, identifying modes and turns (cultural, linguistic, transnational, anthropological and discursive) and wielding the usual trio of ‘post’ words. There was more than ample material for a Sebastian Faulks pastiche.

The strongest chapters, on the other hand, find revealing ways to meet the editors’ request to tell ‘what it’s like to be a historian’ (p. 23). Four authors (Peter Stanley, Stuart Macintyre, Clare Wright and Ann Curthoys) do this especially well and revealingly, but none are more telling and personal than Tony Birch in chapter 14, ‘The trouble with history’, where he explains why he left history for creative writing.

The one worry

An eminent academic specialising in Australian economic and business history commented to me recently, with a certain weariness: ‘The book … seems to take a narrow view of Australian history. Perhaps the forthcoming Cambridge Economic History of Australia … will reclaim some wider interest.’ Is this yielding to a common reviewer temptation, commenting on the book they wished had been written, not that to hand? Or is it something else?

At the end of the Introduction, the editors write:

There are areas we couldn’t include in this collection: what about the histories of religion and science, for example, or the place of economic and political history in the discipline, or even changing understandings of childhood and the family? Many are mentioned in the chapters themselves, but it would have been great to invite discrete contributions on these – and others, no doubt. But time constraints are all too real in this editing game, and there came a point when we had to wind up and send off our manuscript to the publisher (p. 23).

Acknowledging the inevitability of selection and being disarmingly honest are commendable, but why were certain sub-disciplines addressed and so many other areas not covered? What was the case for the particular selection offered? Were those chosen because here can be found the most distinctive current trends in Australian history-making or the sharpest debates or the deepest linkages with the Australian psyche? Don’t know. But ‘time constraints’ are as unsatisfactory an explanation of choices made as the more common space constraints.

No one seems to do this well. In their Introduction to Australia’s History: Themes & Debates (UNSW Press, 2005) editors Martyn Lyons and Penny Russell simply observed that no single volume can be comprehensive, then listed some important areas they left out. In his introduction to What is History Now? (Palgrave, 2002), David Cannadine gave the same selection rationale (silence) in explaining his chapter choices – social, political, religious, cultural, gender, intellectual and imperial history – though he did, like Clark and Ashton, acknowledge numerous others which a second volume might include. Yet presumably neither a random number generator nor a handful of long and short straws were used to decide the actual chapter topics.

Honest History has espoused a commendable and tough standard we will often fail to meet: multiple voices, justified selection, wide context – ‘not only, but also…’. Perhaps I, too, am now reviewing a different book. But imagine a second Australian History Now written, if it must be written, by a mixture of academics, genealogists, independent scholars, blogging doctoral students, Australian Dictionary of Biography regulars, ‘storians’ and some ‘living history’ witnesses. On, say, Australian garden, mining, Jewish, maritime, book, health and criminal history. With an introduction explaining why. Until then, however, we have seventeen good chapters and Anna Clark and Paul Ashton to thank for offering them.