Hynd, Doug

‘Moral judgments, asylum seekers and why historians can be helpful in public policy-making’, Honest History, 12 March 2014

Taking a historical perspective can give depth and clarity to controversial policy issues. The current debate about who is morally responsible for the death at sea of perhaps a thousand asylum seekers over the past year provides a good case study.

I use the term ‘historical perspective’ here to describe an analysis that takes a broader view of events, connections, agents and their motivations and provides a more adequate basis for seriously assessing questions of moral responsibility. Attempting to apply this historical approach will certainly complicate the media debate, however, because it is likely to rule out simple answers and one-track policy responses.

A recent article by Gary Humphries demonstrates the weakness of a narrow frame of reference, one that lacks a broader, historical perspective. Humphries lumbers the Greens with responsibility for the deaths of asylum seekers at sea in recent times; he does so because of the Greens’ supposed influence on decision-making during this period. This assessment of responsibility for these deaths has the rhetorical advantage of scapegoating a minority view.

But the death of asylum seekers at sea is too serious to be the subject of political point scoring. In our inquiries into the circumstances of asylum seekers’ deaths we need to give asylum seekers the respect and dignity of fellow human beings. We need only to ask a few questions before Humphries’s approach becomes revealed as myopic. It occludes from our view and our assessment of moral responsibility a number of powerful political actors.

Refugees, Gare de Lyon, Paris, c. 1914 (source: Flickr Commons/Library of Congress: Bain Collection LC-B2-3252-3)

Why were the asylum seekers in search of protection in the first place?

Primary responsibility for the asylum seekers’ flight must be placed in the hands of those governments, their military, police and other quasi-state actors whose persecution and oppression forced people to flee, seeking asylum out of fear for their life, livelihood and family safety. The Australian intervention in the war in Iraq in 2003 adds another layer of responsibility and implicates Australia in creating the circumstances that created the flow of refugees. The impact of the invasion of Iraq has played a substantial role in destabilising the region, displacing large numbers of people and profoundly disrupting community life in surrounding countries.

Why were asylum seekers getting on the boats?

Governments in this region, including Australia, have failed over recent decades to develop a humane, timely and effective process for dealing with the flow of asylum seekers. This has meant that people are prepared to take great risks because they see no other option. This is made abundantly and heartbreakingly clear in interviews with asylum seekers in Indonesia in the recent documentary Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea.

Why did the boats sink?

Finally we get to everyone’s favourite scapegoat, the inappropriately named ‘people smugglers’. These ‘entrepreneurs’ – targeting a market niche in the spirit of capitalism – are clearly morally culpable for the deaths that occur from sending people to sea in unseaworthy vessels. They should be subject to criminal prosecution on those grounds.

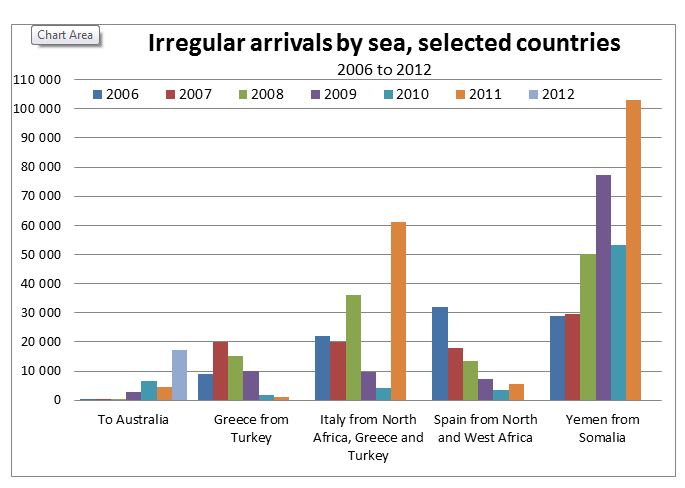

Irregular arrivals by sea, selected countries, 2006 to 2012 (source: Janet Phillips, Social Policy Section, Parliamentary Library, Parliament of Australia, ‘Asylum seekers and refugees: what are the facts‘ [updated 11 February 2013], Parliament of Australia

The entrepreneurs are, it should be noted, being completely economically rational in minimising the costs of their operation, given that the boats will be destroyed by the Australian Government after one voyage. They have no economic incentive to use safe vessels. That does not take away from their moral responsibility in risking other people’s lives. They are no more but no less morally culpable than companies who ignore health and safety regulations at the expense of their customers.

Beyond this, as Australian citizens we are all to a degree morally implicated in these deaths through our acceptance of governments treating the issue as a political football. Vulnerable people have been the butt if not the victims of a totally unedifying partisan struggle for political advantage.

The current Government goal to ‘stop the boats’, even if successful in the short term, addresses a symptom rather than the real issue. In a world where regional flows of refugees from natural disasters and the desire for asylum represent a continuing and recurring humanitarian challenge, Australia’s attempt to isolate itself from this reality is unlikely to be sustainable in the longer term. Indeed refugees from natural disasters in the region are likely to present a much more difficult challenge to policy-makers in future, as George Quinn has recently highlighted.

Historians can help

In teasing out the implications of how we should deal with asylum seekers (and any other public policy issue for that matter) we need to take a long and broad view if we are to make informed moral judgments about who is responsible and what we should do about it. Reflections by historians on the causes and consequences of World War I remind us of what historians can bring to the public policy table. As Mark Hearn observes:

Recent histories such as Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers and Margaret MacMillan’s The War That Ended Peace have argued that World War I was everybody’s fault; all the rival nations connived in pushing each other over the edge into catastrophe.

It was not just the leaders; many citizens embraced the idea of war, even if they could not comprehend how it would be fought. If everyone was to blame in 1914 – if only for misunderstanding the effect of their own choices – doesn’t that imply that we, both leaders and the led, might share responsibility for the problems that plague our world today? Or that at least we should proceed cautiously in pursuit of our ambitions?

Scapegoating minority views while hiding powerful actors from critical attention is not the way forward. The craft and skills of the historian in tracing out the broader connections are a resource that we should draw on to help us inform our judgments.

Doug Hynd was a public servant. He has lectured in Christian ethics at Charles Sturt University and is currently undertaking a PhD in Theology and Public Policy at the Australian Catholic University.

Refugees are welcome main banner: Refugee Action protest, 27 July 2013, Melbourne (source: Flickr Commons; photo: Takver)