‘Highlights reel: historian Mark McKenna writes in 1997 on “black armband history” ‘, Honest History, 10 April 2018

Mark McKenna’s Quarterly Essay 69: Moment of Truth: History and Australia’s Future (2018) considers related issues. HH

***

Historiography, like history itself, has its founding documents; Mark McKenna‘s paper for the Australian Parliamentary Library in November 1997 is one such. Entitled ‘Different perspectives on black armband history‘, it was written when McKenna was attached to the library’s Politics and Public Administration Group and writing for Members and Senators.

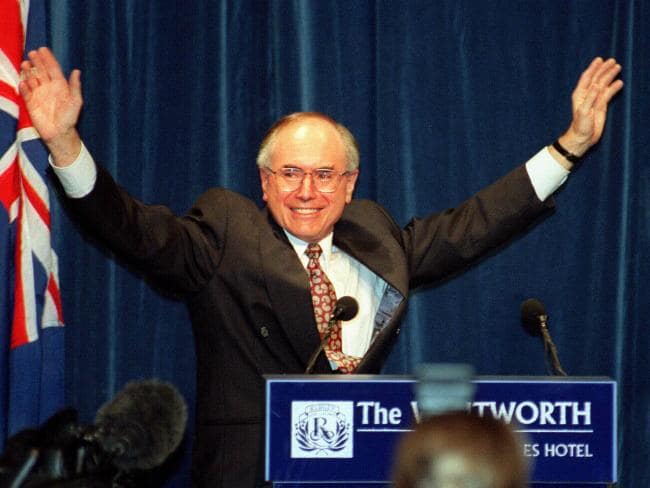

John Howard, election night, 1996 (Daily Telegraph)

John Howard, election night, 1996 (Daily Telegraph)

The paper is, first, a history of the ‘black armband’ concept to 1997, secondly, a discussion of some 1990s debates about Australian history, and, finally, some strong points on the nature of history as a discipline and a national possession. Some of McKenna’s dramatis personae (Geoffrey Blainey, John Howard, Paul Keating, Don Watson) have become more curmudgeonly in the two decades since but still hold much the same views.

McKenna starts by tracing the origins of the black armband view, which he defines, following Blainey in 1993, ‘as a brand of Australian history which its critics argue “represents a swing of the pendulum from a position that had been too favourable, too self congratulatory”, to an opposite extreme that is even more unreal and decidedly jaundiced’. But, says McKenna, the black armband formulation itself ‘is inherently political and a misrepresentation of the work of many serious historians. It is an attempt to appropriate an established symbol of genuine grieving, loss and injustice by those who do not accept, or do not want to accept, that past wrongs must be fully recognised before present problems can be resolved.’

Arguments about – and wearing of – black armbands date back well before 1993, however; McKenna presents evidence from 1938, 1970 and the 1980s. The historian Manning Clark was at the centre of it, writing on 25 January 1988, the day before the Bicentennial:

Now we are ready to face the truth about our past, to acknowledge that the coming of the British was the occasion of three great evils: the violence against the original inhabitants of the country, the Aborigines; the violence against the first European Labor force in Australia, the convicts; and the violence done to the land itself. The rewriting of our past has begun. In radical literature the white man has replaced the capitalist as the chief villain in human history. Our history is in danger of degenerating into yet another variation of oversimplification – a division of humanity into goodies and baddies.

Clark’s first few sentences there exemplify what Blainey would have described as the black armband view. Clark’s final sentence, though, warns against caricature. One of the strong themes of McKenna’s article is how both sides misrepresented each other’s views, the ‘three cheers’ (or Blainey) side admitting more blemishes than the black armband people gave it credit for, the black armbanders giving praise where they believed it was due. ‘The argument’, McKenna insists, ‘is not about content; it is about emphasis. It is not so much concerned with the nature of history as it is with the use of history (emphasis added).’

Mark McKenna, 2016 (ABC)

Mark McKenna, 2016 (ABC)

And so it was. McKenna shows how Paul Keating as prime minister 1991-96 (frequently with words crafted by Don Watson) used a version of Australian history to make telling political points.

Keating’s description [in his 1993 Evatt Lecture] of the Liberal Party’s contribution to Australia as “good little Horatios” who had “held the bridge against national progress” … was but one example of his government’s stereotyping of pre-Whitlam Australia as a “gloomy cave” ruled by a “semi-hereditary elite”.

Keating upset the ‘three cheers’ school – and the conservative Opposition, particularly John Howard – by criticising the British for the ‘desertion’ at Singapore 1942, by other examples of ‘pommy bashing’, and, most of all by his (and Watson’s) Redfern speech of 1992:

“We brought the diseases. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. It was our ignorance and our prejudice.” Keating’s words [says McKenna] attempted to acknowledge the dark aspects of Australia’s past, but they also went much further than any previous or subsequent public statement from an Australian Prime Minister. The use of the word “We” implied that present day Australians should bear responsibility, at least partially, in atoning for the wrongs committed by past generations.

The High Court added to the mix in the Mabo and Wik cases, Justices Deane and Gaudron referring to ‘a national legacy of unutterable shame’.

‘Suggestions of shame or guilt appear to have motivated much of the [anti] black armband rhetoric of both Geoffrey Blainey and John Howard’, suggests McKenna, moving on to a forensic treatment of ‘the black armband debate 1996 and 1997’, with extensive quotes from Blainey articles and Howard speeches.

Promoting his own view of our history was particularly important to Howard, as it had been to Keating. (And to Pauline Hanson, who first surfaced around this time.) Howard defended ‘the Menzies legacy’, and argued that ‘the balance sheet of our history is one of heroic achievement and that we have achieved much more as a nation of which we can be proud than of which we should be ashamed’, while he admitted there had been ‘[i]njustices’ which needed to be remedied – but not apologised for by today’s Australians.

Geoffrey Blainey 2011 (ABC)

Geoffrey Blainey 2011 (ABC)

Meanwhile, Blainey lambasted the High Court, the ABC, ‘high brow dailies’, and other historians, some of whom talked back just as vehemently. Gerard Henderson criticised his fellow ‘conservative’, Blainey, for not naming names – particular ‘black armband’ historians – and Don Watson worried that fears of black armbands might infect school curricula. If that last point seems familiar, it is because it has surfaced periodically since – signalled by the hackneyed phrase, ‘History Wars’ – most recently in the early days of the Howard government, regarding secondary history curricula, in recent discussion of the Ramsay Foundation’s efforts on behalf of ‘Western Civilisation‘, and even in some of the criticisms of the Honest History venture.

For the current writer, as the co-editor of a book that argued that ‘Australia is more than Anzac – and always has been’, the most telling piece of evidence from McKenna, however, was a little vignette from 1996. The then Minister for Foreign Affairs, Alexander Downer, visiting the United States, declined to present the Georgetown University library with a collection of Manning Clark’s six volume history of Australia. Instead, he gave them a biography of Sir John Monash. ‘History has become politicised in a manner not seen before in Australian political life’, comments McKenna. As Prime Minister Abbott might have said two decades later, even historians may sometimes find they need to decide whether or not to pull on the ‘Team Australia’ jersey.

Yet, history remains contested, as it should be. McKenna’s conclusion includes this key paragraph, which is relevant not just to 1997 but to 2018 and, indeed, any era:

As a people, we are trying to come to terms with the fact that “Australian” history is no longer written purely from the perspective of the majority. Historians now ask different questions. History can be heroic or bleak – depending on who is telling the story. For much of our past women, non anglo migrants, and indigenous Australians did not have a public space in which their stories could be heard. Political leaders are now grappling with the fact that there is more than one national story to be told. They are trying to understand how it is possible for Australians to “listen” to different histories and accept the legitimacy of “different” perspectives, while also retaining a shared history which can act as a binding force in the national community.

Eualeyai-Kamillaroi historian, Larissa Behrendt, said something very similar in her chapter in The Honest History Book:

History is not a single story. It is competing narratives, brought to life by different groups whose experiences are diverse and often challenge the dominant story a country seeks to tell itself. There are no absolute truths in history. It is a process, a conversation, a constantly altering story.

Paul Keating at Redfern Park 1992 (New Daily/Twitter/Reconciliation Australia)

Paul Keating at Redfern Park 1992 (New Daily/Twitter/Reconciliation Australia)

McKenna concludes with some words from Bama Bagaarrmugu-Guggu Yalanji man, Noel Pearson, writing in November 1996:

We need to appreciate the complexity of the past and not reduce history to a shallow field of point scoring. I believe that there is much that is worth preserving in the cultural heritage of our dispossessors as a nation; the Australian community has a collective consciousness that encompasses a responsibility for the present and future, and the past. To say that ordinary Australians who are part of the national community today do not have any connection with the shameful aspects of our past is at odds with our exhortations that they have connections to the prideful bits.

Pearson’s final sentence points politely to the incongruity – even hypocrisy – of the words ‘Lest We Forget’ being ritually intoned about military adventures overseas and ‘the fallen’, while we are told to ‘move on’ from invasion and dispossession at home and their legacies.

***

This highlights reel complements Mark McKenna’s just published Quarterly Essay, Moment of Truth: History and Australia’s Future, reviewed for Honest History by Michael Piggott. McKenna is one of Honest History’s distinguished supporters. He wrote a chapter for The Honest History Book (‘King, Queen and Country: Will Anzac Thwart Republicanism?’). His other works include Looking for Blackfellas’ Point: An Australian History of Place and An Eye for Eternity: The Life of Manning Clark.

Also use our Search engine for McKenna’s articles linked to the Honest History site and for Howard and Keating speeches. Stuart Macintyre and Anna Clark wrote The History Wars (2003) about the events McKenna describes. See Robert Manne also. And Margaret Macmillan takes an international perspective.