‘Can we bear Anzac Ted? A review’, Honest History, 8 March 2015

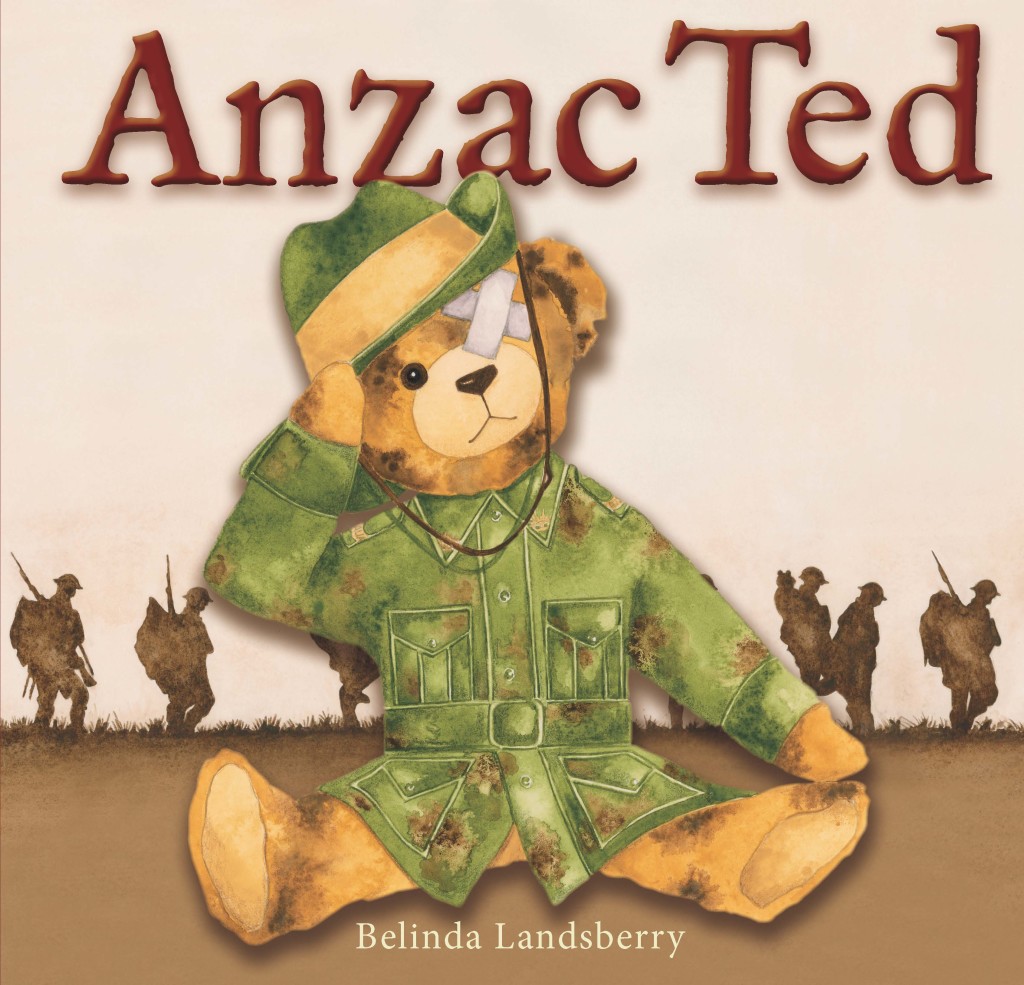

Peter Stanley* reviews Anzac Ted by Belinda Landsberry

At what age do we feel able to introduce our children to the idea and the reality of war and to the many and complex ways we think of it and its place in our world? Is primary school too early? Is middle school too late? Belinda Landsberry is a first-time author who evidently believes that pre-schoolers need to be introduced to Anzac through her character, Anzac Ted. ‘While several children’s picture books cover the world wars’, Landsberry’s publisher says, ‘none has ever made the conflict so accessible to children by telling the story of a bear who went to war’. This, we imagine, is intended as praise, not the indictment it ought to be.

Anzac Ted tells an apparently simple story, though I imagine that three-year-olds – the lower bound of the suggested market (see below) – may have trouble dealing with the time-shifts required to make sense of it (and the language: ‘Mum, what’s a foe?’) Ted is a battered bear whose condition is explained by his having gone to the Great War with ‘Grandpa Jack’, who, though 21, took with him a teddy bear ‘for luck’. Anzac Ted went off ‘to Africa and Greece’ (two places where Great War Anzacs actually saw next-to-no fighting at all, but what else rhymes with ‘peace’?)

Anzac Ted tells an apparently simple story, though I imagine that three-year-olds – the lower bound of the suggested market (see below) – may have trouble dealing with the time-shifts required to make sense of it (and the language: ‘Mum, what’s a foe?’) Ted is a battered bear whose condition is explained by his having gone to the Great War with ‘Grandpa Jack’, who, though 21, took with him a teddy bear ‘for luck’. Anzac Ted went off ‘to Africa and Greece’ (two places where Great War Anzacs actually saw next-to-no fighting at all, but what else rhymes with ‘peace’?)

Ted becomes the soldiers’ mascot and ‘despite the diggers’ dread/ they knew that they would make it through alongside Anzac Ted’. (‘Dad, what’s “dread”, and what’s a “digger” and “make it through” what? And, oh never mind …’) Ms Landsberry includes a seemingly endearing water-colour of a line of helmeted soldiers on the skyline – an image based on Ernest Brooks’s photograph of men of the East Yorkshire Regiment at Frezenberg in 1917. One of them has a teddy bear sticking out of his pack. You might mistake this for a witty or ironic parody in the Blackadder mould, but Landsberry is not playing this for laughs. And nor should we.

Ted comes home ‘a hero’ – though we aren’t told what he does or, indeed, what a hero might be. At the end Ted sits on a bed saluting and the author concludes that, if only people could see beyond his unsightly rips and tears,

They’d see a hero, plain as day,

Who sits upon my bed.

A hero who saved me and you.

His name is … Anzac Ted

Exactly how Ted ‘saved me and you’ isn’t explained or, indeed, even alluded to in the voluminous ‘Teachers Notes’ [sic] on the accompanying website.

It’s hard to know what to make of Anzac Ted as a book seemingly intended for pre-school children. (The publisher’s blurb says ‘readers from 3 to 99’, possibly suggesting that great-grandparents read to great-grandchildren. The publisher’s media release says ‘will engage readers of all ages’. The illustrations depict a little boy of no more than six. A blurb says for ages five and above. The style of the book is early childhood not primary school.) The contrast between the book’s disarming, easy-rhyming, homely-illustrated format and its subject matter – a war in which 60 000 Australians, 18 000 New Zealanders and about 18 million people world-wide did not ‘make it through’, let alone however many more millions became permanently scarred in body and mind – is at the very least challenging. Some might find this incongruous but not offensive: the publisher cites various positive reviews; I would differ.

National defence, c. 1912 (Australian War Memorial ART16026.001/Norman Lindsay)

National defence, c. 1912 (Australian War Memorial ART16026.001/Norman Lindsay)

I should explain that I am not judging Belinda Landsberry from on high. I have been in her position. I too wrote an illustrated book for children (admittedly ‘upper primary’ age), Simpson’s Donkey, in which I too faced questions of what is ‘appropriate’ to say and show. My book presented both war on Gallipoli and in the Middle East and, necessarily, cruelty to animals, both directly and as a result of animals’ use in war. I have to say that I reached different conclusions to Landsberry and presented my story differently. Having faced similar dilemmas I do not agree with her responses.

Because I was directing my story at children five or more years older than Landsberry’s readership (or listenership, since many will not be able to read Anzac Ted themselves) I was able to deal with wounds, death, cruelty or loss more directly. But the real difference between our respective approaches is that I tried to show that conflict was a fact and a part of the lives of animals and the book’s human characters, though my book also had a positive ending. But I did not try to, say, justify the Gallipoli invasion or somehow make sense of the Great War in the Middle East as a positive outcome. Landsberry’s tale, however, is intended to make children feel grateful that bears like Ted risked their lives for our freedom.

The difference between art and propaganda is essentially that art allows readers, viewers or listeners the possibility of forming their own views. With Anzac Ted there is no ambiguity: Anzac Ted is a hero (whatever that is – Landsberry thinks that ‘the Anzacs’ were ‘every one a hero’) who ‘saved me and you’. She is not encouraging or allowing her readers to disagree: they are to imbibe and accept the message that we should revere ‘heroes’ like Ted. As she puts it in a slightly awkward verse,

He never saw a medal,

But some heroes never do.

And we don’t see just how we’d be

Without our Anzac crew.

Landsberry doesn’t see this, but her perspective on Australian and New Zealand history is highly moralising. To emphasise the didactic nature of her enterprise, on her website Landsberry suggests classroom activities such as:

- Compare a modern Anzac with a World War I Anzac … Make a whole class montage entitled ‘The Anzacs Then and Now.’

- Watch the Anzac and Gallipoli specials on TV. Where are the Anzacs now?

- What is a hero? Who are some of yours? Should they be decorated? Why? Design and make a medal for your hero.

- Refer to the book. Discuss characteristics of a good soldier: love, loyalty, mateship, tenacity, endurance, courage, humility, self-sacrifice, mercy, etc.

- What does Anzac mean? When is Anzac Day and why do we commemorate both it and Remembrance Day? What are some of the traditions we observe?

- Where is New Zealand? Why are New Zealanders called Kiwis? Why is it important for Australia and New Zealand to be friends?

Army Bear (Australian War Memorial Shop)

Army Bear (Australian War Memorial Shop)

She is evidently motivated by a sense of patriotism. (In her ‘selling points’ she explains that Anzac Ted is being published just before the centenary of the Gallipoli invasion and she thinks that her book will be ‘especially significant for … anyone with strong patriotic ties’.) But where does education stop and indoctrination begin? This is surely war propaganda in its plainest form. It would be easy to parody Anzac Ted’s classroom activities. Perhaps Landsberry plans a series? She could readily crack the North Korean market with ‘Socialist Sam’ or ‘Communist Charlie’. Classroom activities could include:

- What is a workers’ hero? Who are some of yours? Should they be decorated? Why? Design and make a medal for your hero.

- Refer to the book. Discuss characteristics of a good communist: love, loyalty, mateship, tenacity, endurance, courage, humility, self-sacrifice, mercy, etc. (As it happens, the North Koreans have been keen on a philosophy of ‘juche’ or self-reliance.)

- Where is China? Why is it important for Koreans and Chinese to be comrades?

Classroom teachers will probably ignore Landsberry’s ‘suggested activities’ because they know that few kindy or even junior primary classes are going to be able to actually attempt tasks such as:

- Make a time-line for World War I using the classroom floor. Why did World War I start? Designate children as individual countries to stand on the time line & interact.

- Draw and label a field hospital on the battlefields. What did they do?

- Australia was a new federation when war was announced on 4 August, 1914. What is a federation? How did it change Australia? Why did Australia go to war? Do you agree with this?

Why did World War I start? What did field hospitals do? For pre-schoolers? Are you kidding?

Sadly, Landsberry is not kidding. She has produced a work of Anzac propaganda that provides the perfect accompaniment to the Army Bear, a chubby stuffed bear, clad in camouflage clothing (yours for $29.99). You can buy book and bear at the Australian War Memorial Shop. Unfortunately, Anzac Ted does not come with an age warning: ‘Not suitable for children’.

* Professor Peter Stanley of UNSW Canberra is President of Honest History.

As one who regularly reads to early childhood age grandchildren and has also been a classroom teacher, I am (almost) speechless! I haven’t read the book but it certainly sounds very one dimensional and the classroom activities inappropriate for the intended age. There are 15-year-olds who would struggle with some of those questions!

Hello Nikki

thanks for your kind words. HH did get a freebie copy of Anzac Ted but that didn’t sway me to give it a puff. As ever, Honest History told it as we see it.

As a teacher you’d be very welcome to contribute to the HH website. By all means tell us how you introduce your pupils to historical ideas!

Peter Stanley

From memory, HH received a freebie also but we were not bought off.

To me this is the first honest review I have read about this book…all the other reviews I have read are glowing about how fantastic the story is for using with children (all of those other reviews coincidentally were provided with a free copy).

As a teacher though I found the book to be very “glorified” and not balanced – which is the type of perspective I like to teach my students. I want to present facts and allow them to make up their own mind about war. I would only use this book with older students and in conjunction with more balanced resources to have students debate how authentic the representation of war is in this book.

Thank you for your honest and balanced review. Nikki